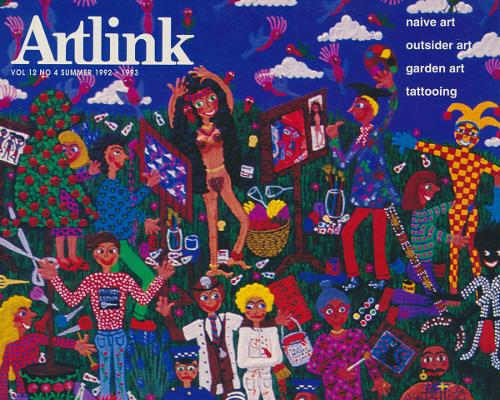

Arts Project Australia: Raising the bar through collaborative partnerships

In 2020 as the pandemic spread across the globe, Arts Project Australia partnered with UK-based Slominski Projects and Jennifer Lauren Gallery to form Art et al. This was in direct response to an identified need for more inclusive programming and better access for neurodivergent, intellectually, and learning-disabled artists to be seen, heard, and to participate in the arts. Art et al. is shaped by Australian and UK advisory groups of artists who self-identify as neurodivergent, and/or intellectually or learning disabled, to provide essential feedback for the intercultural growth of the collective as an inclusive, curated international art platform. Central to Art et al.’s work is commissioning and presenting collaborations between artists from supported studios, artist peers and arts professionals—wherever they live.