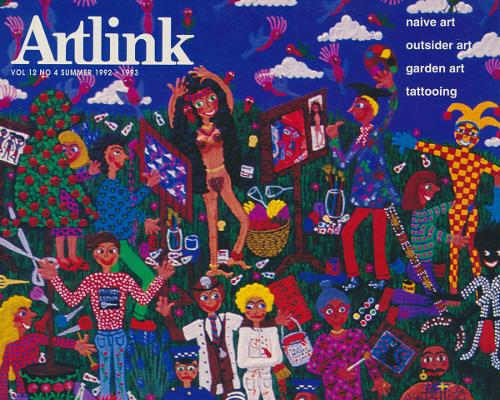

Some struggles are invisible: Art, neurodiversity, and Aotearoa

All struggles are essentially power struggles. Who will rule, who will lead, who will define, refine, confine, design, who will dominate. – Octavia E. Butler. Some struggles are invisible simply because a single word is missing from public discussion. I find that this is particularly the case with words that carry life-giving concepts and that challenge social hierarchies. Their absence can give clues to who might be excluded and what is considered of less value within a given society. One such word is ‘neurodiversity’, and it is missing from exhibition records within some of Aotearoa New Zealand’s leading public art galleries.