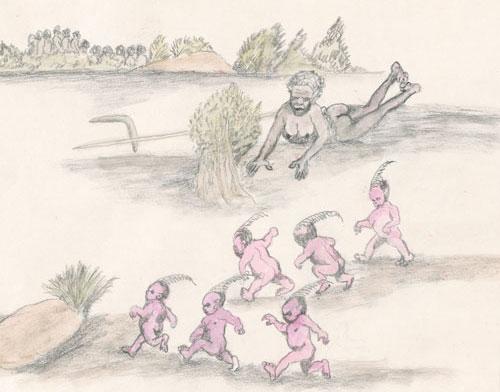

Adam Cullen: Acute misanthropy

Thanks to Erik Jensen’s 2014 book, Acute Misfortune, and its film adaptation of the same name—directed by Thomas M. Wright and released in 2018—the legacy of Adam Cullen, and his Gen‑X revanchism, have crept back into the Australian artworld of late. Both Jensen’s biography and Wright’s biopic are ambiguous, even ambivalent, about Cullen’s actual work. They don’t so much re‑examine his practice as situate it in the background of his embittered, self‑dramatised life, illuminating secrets rather than talents. Jensen concludes that Cullen was likely a closet bisexual with severe mummy and daddy issues; his complicated neediness communicated through lies, innuendos and between bouts of grievous bodily harm caused to himself and those around him.