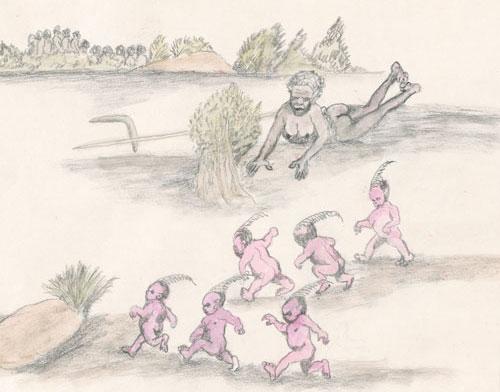

Hayley Millar-Baker: I will survive

Aboriginal stories are tales of survival, of attempted genocide, of strength and resistance. These are the narratives we share, the heritage we cannot avoid even if we wanted to. Colonisation and attempted genocide is part of Australia’s history and identity, no matter what we desire. It is our story to tell. Indigenous people owe our lives to the resistance of our elders.