In this world of bio links and bio pics that ID and connect us, you are perhaps never more than one click away from sharing your story with the rest of the world. Thriving on the promise of instant accessibility, and on the erosion of the boundaries between the public and the private, self or other, a similar sense of agency defines the evolution of the contemporary biopic. Once the preserve of a top-down star system, cultural production is increasingly led by self-determining forms of documentary, biographical or life writing, and ideas of portraiture in the expanded field.

As the opening feature, with a focus on the artist biopic in cinema history, Adrian Martin provides a magnificent overview of key works in the genre that define its medium and métier, from Goya’s Ghosts (Dir. Miloš Forman, 2006) and The Mystery of Picasso (Dir. André Bazin, 1956) to an artist video by Kurdwin Ayub, LOLOLOL (2020), a 20-minute snapshot of two young women artists as they take in the randomness of life and attend an art fair in Vienna. Under Martin’s piercing gaze, the emphasis goes beyond the Romantic, often pathologising, focus on difficult relationships and a torn inner life (frequently ending in death) to a more fulsome analysis of the social, material and technological processes that impact the lives of artists and determine the production of the work.

A tantalising if troublesome genre, the artist biopic can be a rollercoaster, weighed down by misplaced emphasis in the artist’s back story. These distortions are represented in Martin’s analysis of Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck’s Never Look Away [Werk ohne Autor] (2019), based on the life of Gerhard Richter who famously pulled his involvement, drawn to our attention by the reference to Roland Barthes’ cult essay “The death of the author” in the original German title. Closer to home, Wes Hill writing on Adam Cullen responds to Acute Misfortune (the film by Thomas M. Wright based on the book by Erik Jensen), to consider a further encounter which does not end well for the artist or his biographer.

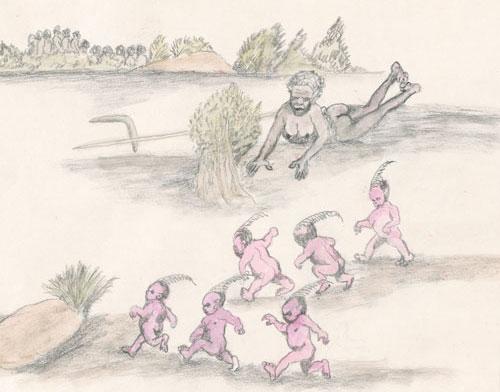

In other encounters that support the relational impacts that reverberate across our national culture, Sasha Grbich writing on James Newitt’s video work, talks to working with the troubles through shared discourses of retreat; while, Claire G. Coleman applies her incendiary voice to the series I Will Survive by Hayley Millar-Baker to embody the continued legacy of Aboriginal genocide; and, reflecting back on the remarkable oeuvre of Butcher Joe Nangan, Stephen Muecke shares a memory of a haunting apparition that is his tribute to a vision of the possibilities of negotiating this great cultural divide.

This concept of looking on, and listening in to the lives of others is further extended in profiles on artists that include John Mateer’s response to Wendelien van Oldenborgh’s Bete and Deise (2012), unpacking the ideological differences between two Brazilian artists from different generations and social strata that impact their life circumstances; and Alexandra Heller-Nicholas provocative case studies of the work of Tracey Moffatt, Caroline Garcia and Morgana Muses (working with filmmakers Josie Hess and Isabel Peppard) to further disentangle, genre, gender, social and racial bias as notable exclusions in the history of the biopic. A gendered approach to the subject is also determining in Amy Weng’s discussion of female bodily dissociation and practices of self-surveillance in the work of Meg Porteous; and Faye Neilson’s profile on Braddon Snape performing violent masculinity in a recent exhibition for The Lock Up in Newcastle.

No longer irreducibly singular, but often multiple, hybrid, defined by broader collective agency, Jacqui Shelton describes the experience of listening to Archie Barry’s audio work Multiply (2020) as a veritable lifeline during Melbourne’s Covid-19 lockdown. It seems fitting then to conclude with Amos Gebhardt’s Small acts of resistance (2020), a photography series and new video installation commissioned by the Samstag Museum of Art, discussed in the richly layered essay by Anne O’Hehir. The family portrait featured on the cover, as a detail from this expansive work, is an extraordinary collaboration between the artist and community of friends playing themselves in a reimagined and hyper-visual play on the nativity scene.