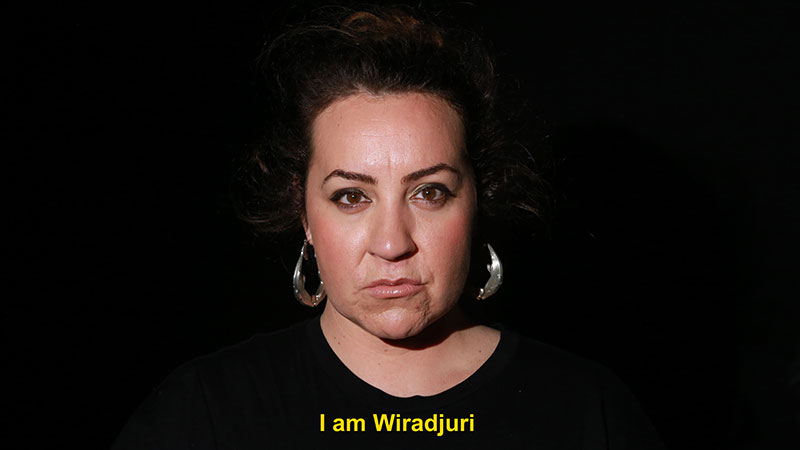

Two women inexplicably hammer at scaffolding inside a disused warehouse space; the golden years of Hollywood’s glamorous history are evoked by Joan Crawford and Bette Davis, but with a distinctly noir twist; an Indigenous woman repeats the phrase “I am Wiradjuri”; Bollywood dancers shimmy and shake; art history’s reclining nudes playfully dance across the screen; a fluorescent yellow couple move through a colonial painting by John Glover; boys play indoor soccer; a woman paints herself into a corner before painting herself white. Welcome to the exhibition Moving Histories // Future Projections.

The brief to the curators Kelly Doley and Diana Smith by dLux MediaArts was quite straightforward: curate an exhibition examining the current state of screen-based practice by women artists from New South Wales. The result? A diverse selection of leading female contemporary artists working across screen-based media including video and stop motion animation. The subjects range in tenor and tone, from joyful art-historical interventions to serious mediations on cultural identity and retrievals of marginalised histories.

Touring regional galleries until 2019 by Museums & Galleries of NSW, Moving Histories // Future Projections is to be applauded for making available to regional audiences a challenging and heterogeneous selection of works. One of the immediate curatorial challenges presented by the medium is obtaining enough gallery space to physically display the works. This has been pragmatically overcome with the solution of projecting the works on a single screen in a continual loop. Conversations and juxtapositions are created in new and unexpected ways.

With no finite beginning or endpoint, I entered the gallery space halfway through Mikala Dwyer and Justene Williams’ collaboration Captain Thunderbolt’s Sisters (2010). The experience was akin to the vertiginous feeling of falling down Alice’s rabbit hole and being transported to a barely recognisable space and time. Two women climb a scaffolding structure in what could be a disused warehouse. Dressed in prison smocks and high heels, they beat the scaffolding repeatedly with hammers. With no context to draw from, the spectator is immediately plunged into a surreal interior with no easy explanations or conclusions.

One of the most satisfying aspects of this exhibition is its investigation of history. Against a fixed or linear formulation, history is understood here as something labile and flexible. Gaps and absences are probed, as artists reimagine well-known narratives and generate new lines of enquiry. Sydney’s brutal convict history is evoked by Dwyer and Williams. Bushranger Captain Thunderbolt famously escaped Cockatoo Island. But Cockatoo Island is also home to less well-known histories, such as imprisoning women considered “wayward”. It is these invisible women’s lives that Dwyer and Williams reanimate.

In the 1930s, the notion of a plurality of co-existing temporalities was described by German writer Walter Benjamin in the Arcades Project as a crystal of time. Frustrated with linear or chronological models of history in the lead up to World War II, Benjamin sought to understand images as temporal crystals, a collision between the “Now” and the “what-has-been.” The temporal relationship here is not linear or causal implicit in a continuum between the present and the past, but a collision, “an image that emerges suddenly, in a flash.”[1] This collision is epistemological, a type of thinking in images. The constellation of the “what-has-been” and the “Now” comes together in a flash, akin to a crystal’s blinding light.

Understanding history as a flexible mode of enquiry is akin to Benjamin’s crystal. Temporalities rebound, bend and swerve. Crystals alter and disperse light in a myriad of unexpected ways. Refraction scatters and fragments. As light enters the crystal, passing from one medium into another, its speed is altered and obliquely dispersed, changing direction. Like the alteration and dispersal of light, the crystal image opens new possible modes of enquiry.

In 1968 Australian anthropologist W.E.H. Stanner presented two Boyer lectures (commissioned by the Australian Broadcasting Commission) titled “After the Dreaming”, the second of which was called “The Great Australian Silence.” Stanner argued that the preoccupation of historians with issues pertaining to Australian nationalism and Federation had served to obscure critical areas of Indigenous history such as invasion, theft of land and massacres. This structural imbalance in Australian historiography is the subject of a collaboration between Dharug Elder and Song Woman Jacinta Tobin and Kate Blackmore in Ngallowan (They Remain) (2014). Having completed painting the walls white, Blackmore is shown painting herself literally into a corner, before turning the brush on herself. The camera cuts to Tobin’s singing. The juxtaposition is jarring, leading the spectator to reflect on the ongoing resilience of Indigenous culture in the face of the whitewashing of history.

As a medium, film and its attendant forms such as video and animation are particularly well suited for investigating time. Philosopher Gilles Deleuze also took up the image of a crystal to describe the non-linear movement of time. Deleuze writes, “And what do we see in the perfect crystal? Time, but time which has already rolled up, rounded itself, at the same time as it was splitting.” Time is understood as separating so the past and present co-exist, as if “dividing in two.”[2]

Amala Groom’s The Invisibility of Blackness (2014) encapsulates a sense of time splitting and moving simultaneously in multiple directions. With the camera trained on herself, Groom repeats the phrase, “I am Wiradjuri. My mother is Wiradjuri. My grandmother is Wiradjuri …” With each preceding generation, the screen slowly fades to black, leaving only Groom’s disembodied voice creating a bridge between her past, present and future cultural identity. The spectator is left to contemplate the loss of culture, suggested by Groom’s regression into blackness while simultaneously pointing to its resistance and optimistically pointing to the future.

The loss and endurance of tradition is taken up by Angelica Mesiti in Play (2015). Mesiti continues her investigation into the dying linguistic form of whistling languages in earlier works such as The Calling (2014). In Play, Mesiti examines this complex system of whistling as a form of communication in a surprising event: an indoor soccer game played by young boys. Ultimately, Play is redemptive. Whistling as a language is continued in the form of a game, reflecting the unexpected ways cultural histories persevere and survive, creating folds in time.

Akin to the fragmentation of light in Benjamin’s crystal, time is split in Joan Ross’s animation Colonial Garb (2014) as time travel. With an ironic nod towards Donald Horne’s The Lucky Country, a poker machine win projects the spectator through time and space, creating collisions between Ross’ signature fluorescent yellow and colonial landscape painting. In one scene, a colonial couple dressed in fluorescent yellow enter John Glover’s painting Natives on the Ouse River, Van Diemen’s Land (1838). The painting is animated by Ross so the fire literally crackles. Complete with 1970s blonde brick house and a wandering dog, Glover’s trees morph and pulse as the spectator is transported through multiple temporalities.

With its capacity to disrupt chronological narrative, montage serves to disperse and fragment, only to be reassembled in a potentially infinite number of ways. If the past survives in the present, montage as a mode of disruption is utilised in Deborah Kelly’s Lying Women (2016). Art history’s most famously reclining nudes are reclaimed in a playfully animated collage selected from discarded text books. Kelly’s hand moves in and out of the frame, repositioning the nudes periodically, as they happily dance across the screen. The self-reflexive gesture incorporating her own hand opens the work to a haptic sensation of touch and sidesteps an entire art-historical discourse pertaining to the female nude and the male gaze. Kelly’s hand collides with the “what-has-been” past of these reclining nudes, shifting to the “Now” of her own contemporaneity and position in art’s history.

The use of appropriated and re-purposed material is continued with Soda_Jerk in The Time That Remains (2012). Using two channels or screens, the spectator is presented with a montage selected from various films to create encounters between past and future selves of Joan Crawford and Bette Davis. The ghosts of cinema’s history come to life as the screen is filled with motifs of windows, doors, mirrors, and the unnerving ticking of clocks. Soda_Jerk edited the original material to create new narrative structures, and alternative co-existing temporalities. The dual-channel format creates a collision; as one character sleeps, the other is trapped sleeping in their own cinematic space. Time is split: physically between the screens; and internally, as the characters confront past and future selves.

.jpg)

The repurposing of pre-existing Hollywood material is also the subject of Caroline Garcia’s Primitive Nostalgia (2014), but to entirely different ends. Drawing heavily from iconic dance sequences of the 1960s, such as Gidget goes to Hawaii (1961) and the mambo dance scene in West Side Story (1961), Garcia mischievously probes Hollywood’s colonial stereotyping by inserting herself into the camera’s frame using a green screen. Garcia deploys montage as a tool to disrupt; her joyful presence interrupts the pre-existing flow of the dancers’ moves. Garcia is the cultural “other” in the series of dances, which are themselves Hollywood fantasies of cultural otherness.

Moving Histories // Future Projections highlights the free-ranging and open-ended preoccupations of contemporary women’s screen-based practices. The exhibition is particularly suited for an investigation of temporal structures that do not conform to a past–present–future configuration. The coexistence of a plurality of possible histories underscores the curators’ goal of opening established narratives to new dialogues and interventions. The crystal image reminds us that historical truth(s) are plural, fragmented and dispersed. The crystal merges the past and present tense of its viewing, creating new possible histories and future lines of thought.

Footnotes