.jpg)

The 60th anniversary of the first of seven nuclear tests and hundreds of minor tests at Maralinga is the impetus for an exhibition that looks at the impact of those experiments. Anyone who lived through the height of the Cold War between the United States and the USSR lived against the backdrop of the threat of a nuclear war. In Australia, the testing of the weaponry that would form the nuclear arsenal caused deep impacts on the country and profound impact on the vast Maralinga Tjarutja area. The Anangu people who lived there at the time of the tests were moved off their land to Yalata to make way for the experiments and that was just the beginning of the deep suffering caused. But they did not escape the impact and were profoundly affected by the black mist that blew over them.

Jonathan Kumintjarra Brown was born on the Ooldea mission at Yalata but became a member of the stolen generations. He found his way back to his family and traditional lands later in life. He also found the visual arts to be healing and became one of the most prolific artists to document the scarred landscape around Maralinga. And it was his Maralinga Before the Atomic Test (1994) that proved to be the muse for this exhibition. In bold black, white and burnt orange ochres, the work uses the dot art style to represent connection to country and the strength of kinship ties. Curator JD Mittmann came across the piece and, influenced by his own experience of growing up in a divided Germany under the threat of nuclear holocaust, raised questions about the way in which Maralinga was viewed after the testing.

.jpg)

Even though Maralinga Before the Atomic Test (1994) is not included, Jonathan Kumintjarra Brown’s three powerful works that do appear have a gravitational pull. In Black Rain (1995), plumes of black smoke against imposing white lines evoke both the power of the explosion that dominated the horizon and the long, lingering, lethal aftermath. In a crater, a group of figures are outlined and entwined, representing the Anangu people who were still on the deep orange country when the bombs were dropped. The sky looms ominously over them, foreshadowing a lethal fate. The most striking work is Frogmen (1996) masked men, like aliens, float in the canvas, standing against the brown earth backdrop as though emerging from dust. The outlines of the foreigners who undertook the testing in their protective suits and masks resemble the sacred wandjina figures, themselves an evil spirit. The British personnel who participated in the testing themselves suffered from the effects of exposure to radiation.

In Maralinga (1992), the stark brown dust covers fragments of a dot painting, its connections obscured under the red soil. We know they are there, as though the dust can only cover over but never erase connection to kin and country. The colours and the dots and links evoke the original inspiration for the exhibition, Maralinga Before the Atomic Test, and speak to the drastic changes to the land – and to the Anangu people and their culture – before and after the atomic testing. A tiny lizard in delicate skeletal form is poised in the centre of the painting, scorched into the earth around it and reminding us of the obliteration of life from the force of nuclear energy. Brown passed away in 1997 but his works, scattered throughout the exhibition, leave no doubt as to his passion for his country and the wrong that was done to it and his people who remain the traditional owners.

Alongside Maralinga is Sidney Nolan’s Central Desert: Atomic Test (1952–57). Nolan’s landscape sits harsh and red under a blue sky and the mushroom cloud of the bomb. Nolan was living in London at the time but news of the tests started appearing in the media. The cloud and dust were added to one of Nolan’s desert paintings as an act of protest over the events taken place back in Australia and the addition turns a rugged landscape into an image that seethes with anger at the act of destruction. In Nolan’s landscape, the bomb looms large. By contrast, in Arthur Boyd’s Jonah on the Shoalhaven – Outside the City (1976), the iconic cloud sits on the horizon, almost like a puff of dust rising off the white sand. Boyd had been conscripted into the army and became a pacifist. For him, the threat of nuclear destruction sits in the backdrop, no less menacing than Nolan’s apocalyptic response two decades earlier.

Karen Standke’s Road to Maralinga II (2007) faces Brown’s Maralinga and proposes a hyper-realistic interpretation of the same environment as grey clouds that could just as easily be clouds of dust as full of rain. They cast a grey pallor against the tufts of grass and the red landscaped scarred with the tire tracks of unseen vehicles.The empty yet altered landscape takes on different moods with Rosemary Laing’s , One Dozen Considerations Totem 1 – Emu (2013) monument marking the site of an weapon’s test with a British flag flying behind it. Both look like conqueror’s claims to territory, powerful images of the attempts to colonise Indigenous space, to write a colonial history through markers of significance, to write out the Indigenous voice but at the same time to appropriate Indigenous ideas and language.By contrast, Paul Ogier's One Tree (former emu field atom test site) (2000) sees a landscape shrouded in a mist. A tree stands out boldly. Here is another way in which Indigenous history and connection has become obscured and covered up. A well-worn path of tire tracks in the soil is the only indication that this land has been colonised. But against this desecration, the landscape endures. Eventually, we can see, the grass will reclaim the ground that now is laid bare.

Amongst the rich, strong imagery in Black Mist Burnt Country sit Judy Watson’s bomb drawing 1 (1995) and bomb drawing 5 (1995), delicate teardrop watercolour marks whose fragility juxtapose with the devastating impact of nuclear warfare against the tenuousness of life and our survival as a species. How can dust something wreck so much damage, she seems to ask? As the curated works show, nuclear testing in Australia inflicted a deep wound on the landscape and on the Indigenous people who lived there. The McLelland Royal Commission in 1984–85 would eventually investigate the activities around the impacts of the Maralinga testing and the treatment of the Anunga. It detailed for both the Indigenous people and the British military personnel who were exposed, the impacts did not just affect their health and lifespans but left a legacy through future generations who suffered medical problems and deformities. The Royal Commission was presented with evidence that Aboriginal people had walked barefoot over contaminated ground because the boots they were given didn’t fit. And it also concluded that levels of contamination were much higher than other officially recorded by the British.

This legacy is captured in the image of Aboriginal man Yami Lester who was a tireless campaigner for Aboriginal people. As a child, Lester was blinded by the poisonous black mist and stands staring into the sun with his sightless eyes closed, re-enacting the moment of destruction. In Belinda Mason’s Maralinga (2012) is a holographic image of Lester’s open eye. It stares, probing, asking questions, even though it cannot see. He is also the subject of Jessie Boylan’s Yami Lester, Wallatinna Station, South Australia (2006) where his face contorts, as though in pain, in a pose the re-enacts his reaction to the black dust that once blinded him, taking his sight permanently. This portrait of a tireless campaigner is complimented by Boylan’s portrait Avon Hudson in his room of archives, Balaklava, South Australia (2014). Avon was considered a whistle-blower on the true impact of the nuclear testing and the subsequent cover up and he confronts the camera, world-weary but determined.

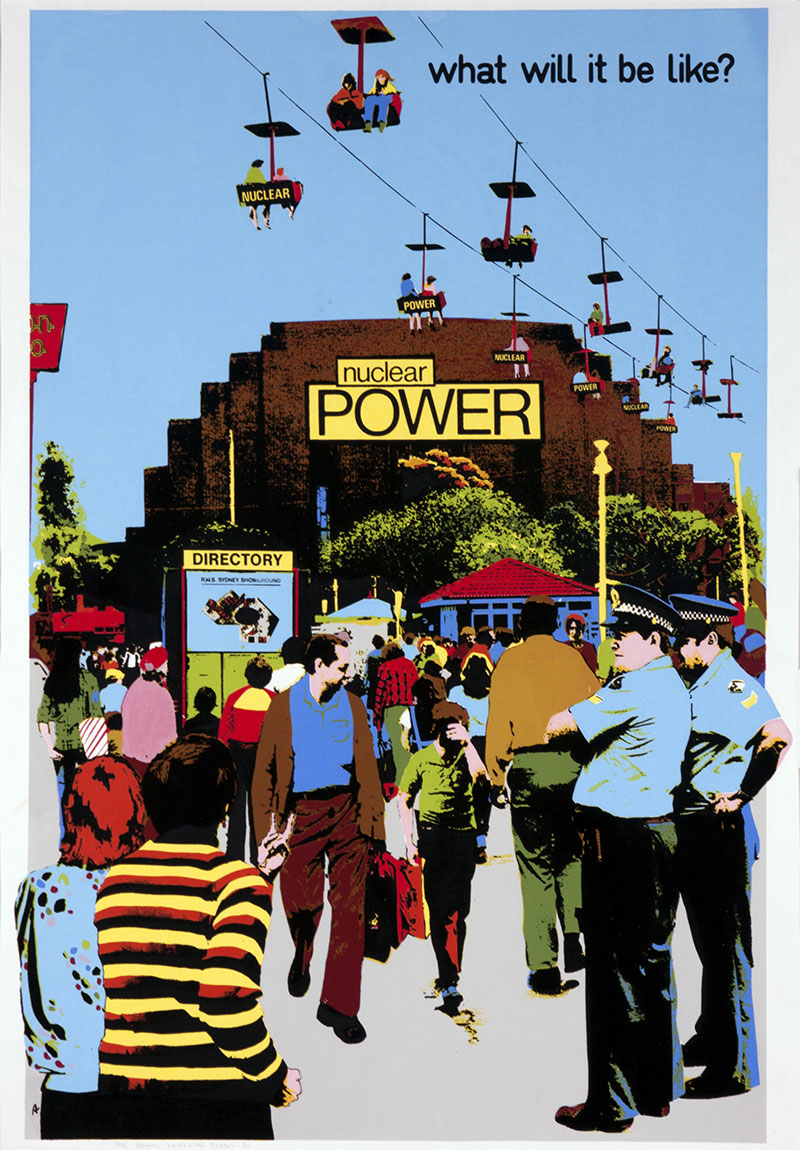

These images of campaigners provide a human element to the anti-nuclear movement. Other artworks capture aspects of the “people’s protest”. From Luke Cornish’s Wake up to the Stink (2009), a pop-art style with a Jesus-figure donning a crown of thorns and a gas mask to Pam Debenham’s textual No Nukes No Tests (1984) and blunt graphic depiction in Hiroshima 40 Years (1985) to Toni Robertson and Chips Mackinolty’s domestic nuclear family in Daddy what did you do in the war? (1977). Toni Robertson’s The Royal Nuclear Show – 3 (1981) and The Royal Nuclear Show – 6 (1981) mock the way in which governments and industry tried to promote nuclear experimentation as necessary for safety and security. These works are juxtaposed with Kim Bowman and Susan Norrie’s Black Wind (2005) that pays tribute to the protestors who lined the streets, barricaded and dug in through a black and white montage of life in the protest camps, with images of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy in Canberra drawing the connection between the anti-nuclear and the land rights movement and the way in which it is Indigenous Australians who continue to be marginalised by mainstream politics even when they are the most deeply affected by government decisions.

The machinery of war is confronted in Ian Howard’s imposing imprint of the Enola Gay, created by rubbing crayon references the machinery of war – mechanical and industrialised. Enola Gay (1975) is imposing in shape as it replicates a slice of the plane that delivered the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima. By focusing on the nose, Howard produces imagery that suggests both the nose of the plane but the shape of a bomb as well. This work on paper is above a sea of fragile but brightly coloured paper origami cranes, a symbol of Japanese culture and life that was obliterated by the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Blak Douglas (aka Adam Hill) has contributed Tjarutja Tragedy (2016) and sees a return to his iconic graphic design style. Trees bend away from a blast, their branches splitting into Ys – as if asking that very question – why? Blak Douglas uses clouds as a symbol of government complicity – they are white and fluffy, but without substance. Here they hover above as a ghostlike figure, carrying traditional weaponry, walks towards the sun, towards home, towards ground zero. It speaks to the deep displacement of Indigenous people that resulted from the tests. Hills graphic design styling sits comfortably amongst the protest art that peppers the exhibition but it resonates most strongly with the other Indigenous voices, particularly those from the Yalata community – Mimi Smart, Hilda Moodoo, Jeffrey Queama, Terence Edwards and Yvonne Edwards. Their work tells of the human and cultural cost – of being moved, of contamination, of destruction of country and of a way of life.

Although this exhibition sets Indigenous artists alongside non-Indigenous artists, it is the generational differences that are the starkest. In one of the pieces commissioned for the exhibition, Jessie Boylan and Linda Dement have developed an installation, Shift (2016), captures the moods and mystery of a black and white landscape across three screens. It is ghostlike and ethereal, as fragile as it is beautiful. In contrast, underneath, is a rotation of weapons, pointed at the viewer, a reminder of what could come from the sky from the arsenal of warheads. Although most of the work sits under the bleak shadow of a nuclear cloud, Tjariya Stanley’s Puyu – Black Mist (2015) sits in bright colours that show tracks over the green and brown land. The colours are joyous, hopeful. There are ceremonies and song-lines that connect people. It is forward looking and reminds us to never underestimate the resilience of the world’s oldest living culture. As we feel seismic shifts in the world, the looms large once again. In 2015, the Science and Security Board moved the Doomsday Clock forward to three minutes to midnight noting that “the probability of global catastrophe is very high” and that “the actions needed to reduce the risks of disaster must be taken very soon”. In this environment, Black Mist, Burnt Country reminds us that the greatest threat to humankind and our planet are ourselves.

.jpg)