In the exhibition 9/11, you have to look down to see Eugene Carchesio's Small Cardboard Rectangles (2011) leaning on the gallery wall. Carchesio captures the conceit of many of the artists on show here that representing 9/11 demands something more subtle than monumental. For while it has become a truism that 9/11 changed the world, the enigmatic footage of the falling towers has been subsumed into a greater scene of permanent war. To name 9/11 is no longer to name its event, but to describe its violent aftermath in Africa and the Middle East, to bring to mind the new visibility of Muslim minorities and regimes of surveillance in the West. To rewrite the significance of 9/11, to visualise and memorialise the event differently and self-consciously, is to rewrite this history. So that in the small watercolour painting Osama bin Laden (2015), Lucy Griggs captures the terrorist’s humanity and vulnerability, his soft white robes covered by a camouflage jacket. The other woman in this exhibition of eleven artists is Madonna Staunton. Her dark monotypes of obliquely clasping hands allude to the awful mood of 9/11 rather than to its iconic imagery.

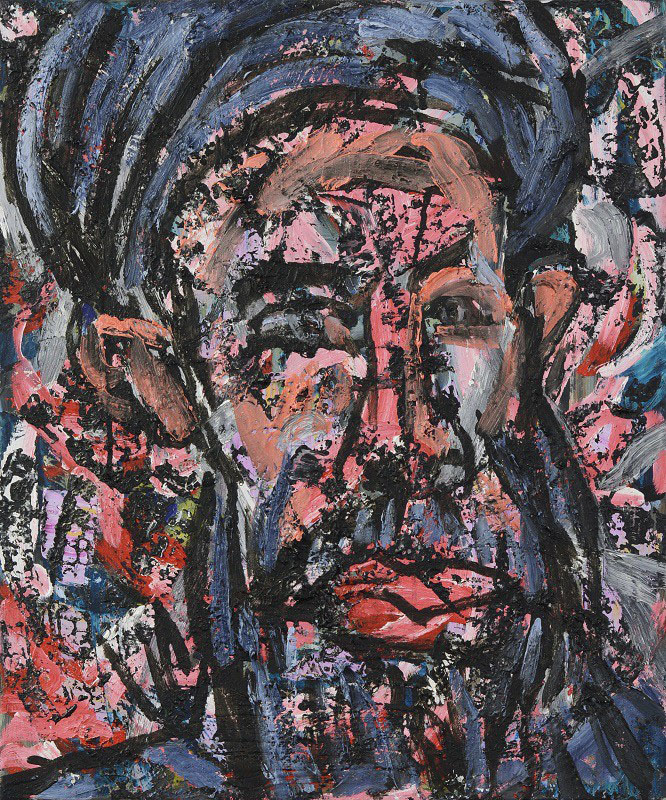

In a very different kind of intimacy, Richard Larter puts photographs he has taken of naked young women atop news clippings of the towers exploding, in an over the top collage of visual information. The artist closest to the violence here is George Gittoes, who directs and produces films in Afghanistan, and is in an ongoing negotiation with the Taliban for the safety of his studio. His portrait Moulana Gul Badshah (2009) is of a local religious leader who had been threatening to kidnap Gittoes and his partner. Gittoes heard about the threat, invited him to share tea and painted his picture. Its expressionistic style captures something of this intense situation, and stands apart from the more self-conscious conceptualisms of the other works on show.

Gittoes is one of three artists in 9/11 not represented by Brisbane’s Milani Gallery, while another eight come from its stable, including Christian Capurro, Richard Bell, Gordon Bennett, Stuart Ringholt and Khaled Sabsabi. To see some of these high profile artists in an impoverished ARI, rather than in big institutions or in Milani itself, is testament to curator Chelsea Hopper’s audacity as much as it is to the politics of an exhibition that addresses big questions with humble answers. For as much as the artworld would like to declare itself outside of the politics of war, artists are paying taxes to a country that pays for combatants in Afghanistan and now Iraq. At a seminar held as a part of the exhibition, Gittoes outlined his fears about new military technologies being rolled out in these war zones, and the way that mass surveillance has become part of everyday life in Australia. That we might imagine 9/11 differently offers a way of rethinking Australia’s misspent energies, and to look closely at what new and even more formidable scenarios are being thought up in its name.