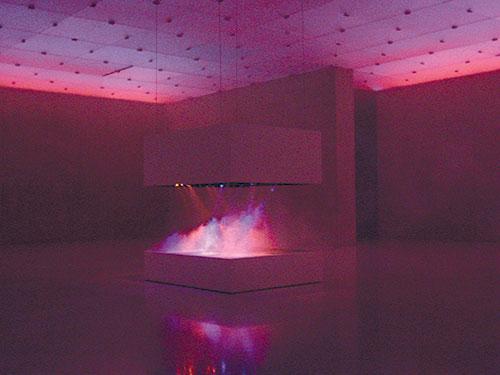

Back in November 1982, Brisbane's beloved Cloudland Ballroom was demolished in the dead of night, despite its National Trust listing. Currently, in her exhibition Cloud Land, Robyn Stacey presents large-scale photographs of camera obscura imagery of iconic sites projected onto interiors of high-rise hotels, offices, institutional spaces and airports to unite the past and present of Queensland’s capital city – also known as "BrisVegas". Capturing its unique and often transient sense of history and place, Stacey tapped into a deeply felt, personal knowledge of her subject, liberating her eye to create her most direct, immediate and eccentric work to date. Lyrical and crisp, Cloud Land packs together lush visuals with a surreal, poetic irony kept in check by Stacey’s rigorously disciplined approach of bringing ephemeral outdoor scenes captured through a specially designed pinhole lens into rooms devoid of any other light.

The work feels freshly minted and very much of the present. In Room 710, Tower Mill Motel, Carlos (2015) the camera obscura image of the Windmill (Brisbane’s oldest extant building, convict built) is surrounded by purple jacaranda blossoms and brand new skyscrapers. Within the hotel room, (once flash, now a mere backpackers’ hostel), Carlos leans his forehead against the gyprock partition separating the bedroom section from the bath. The scarlet red of his hoodie creates a visual connection to the bright red architectural details of Suncorp Plaza far across Victoria Park, now brought inside and pictured on the wall beside his left hand. Space and time are flattened into a geometric composition including 19 –century colonial pragmatism, redolent of a Mondrian or Sol Lewitt composition, yet softened by the model’s mysterious, contemporary pose and presence.

Stacey, born in Brisbane, tells the story of how she withstood the repressive Joh Bielke-Petersen years, playing in an all-girl punk band and attending political demonstrations (Room 710 brings back memories of running away from the police, past the Windmill, at the 1971 Springbok rally), resulting in a 24/7 police presence parked outside her West End share house. She left friendly, ultra-conservative Brisbane for Sydney as soon as she could. The Museum of Brisbane’s invitation to create portraits of the city marks her first return to work here.

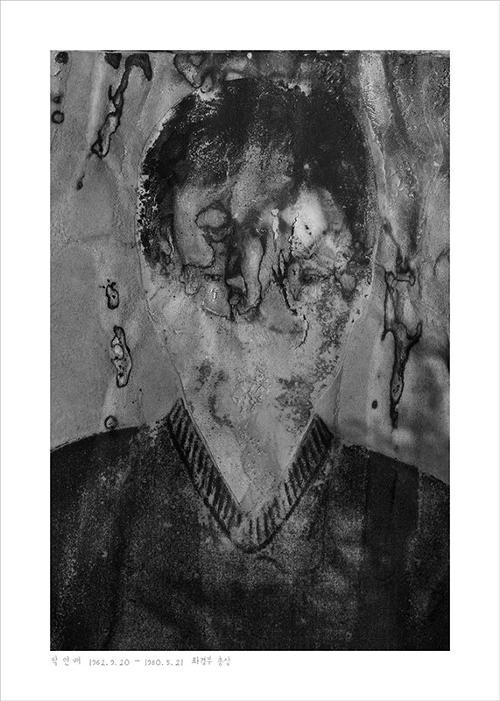

Her photography’s ability to capture history’s slipstream of fact and fiction, while employing a self-possessed, almost documentary eye have been hallmarks of much of her work. Yet in Room 930 Royal on the Park, Maroochy Barambah Song-woman and Law-woman Turrbal people (2015) her portrait of Maroochy dressed in traditional grass dress and kangaroo skin, holding a ceremonial staff and wearing ceremonial paint becomes something more. Her subject’s fierce gaze and monumental centrality, shadowed against the camera obscura projection of the dense greenery of Brisbane City Botanical Gardens and a crystal blue sky is a powerful call to Country and a re-inhabiting of occupied lands. The success of this work as a social document lies in its bypassing the indexical agency of photography. It mixes the camera obscura’s ephemerality with the interiorised sovereignty of indigeneity, and the exterior garden, brought inside to assume a changed presence.

The photographs in Cloud Land would be impossible to restage or recreate – they document a discreet moment. Ultimately, Stacey’s unsentimental use of an immeasurable past allures the viewer because it works to undermine the authority of linear time.