.jpg)

The opportunity to present this exhibition by Matthew Barney, only the second showing after Munich's Haus der Kunst, is a major coup for MONA. You can see the provocative mind of David Walsh and Co. at work here (in liberal ways publicly funded institutions shy away from) in mounting an exhibition, derived from a five-hour filmed performance, based on a novel by Norman Mailer in which the titular theme, River of Fundament, refers to the fluid passage of human waste.

Doubling the 'crude thoughts and fierce forces’ of Mailer’s 1983 novel Ancient Evenings, as a convoluted meditation on the death, serial rebirth and resurrection of its ancient Egyptian protagonist, this re-staging by Matthew Barney (with composer Jonathan Bepler) imposes a further narrative in the reenactment of Norman Mailer’s own wake (following the author’s death in 2007). Remarkably, this takes place in Mailer’s Brooklyn apartment reconstructed on a barge that proceeds for the duration of the film down New York City’s East River.

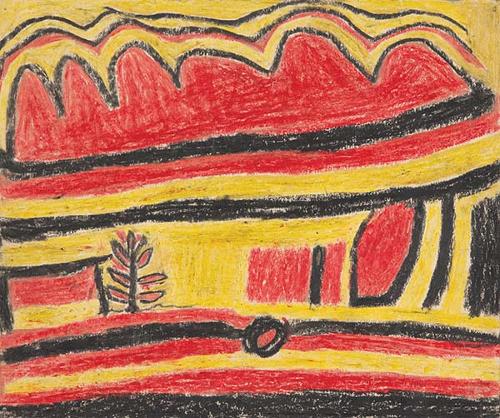

Making sense of the scenes of oratorical and bodily excess, also in reference to the Egyptian mythology based on the Book of the Dead requires some dedication to the program notes. So, too, acknowledgment is required of the cast of hundreds, who perform as soloists, chorus and attendant workforce for the actions that take place in the dramatic riverside, industrial settings of Los Angeles, Detroit and New York. Structured around the seven stages of the soul’s departure from the body as it passes from death to rebirth, and the triple reincarnation of the main character of the novel, the narrative is fantastically interspersed with the ritualistic destruction of the great American car as stand-in for its human subject. Variously incarnated as the 1967 Chrysler Crown Imperial from Cremaster 3, a grand 1979 Pontiac Firebird Trans Am and a 2001 Ford Crown police car (dramatically hoisted out of the river by crime scene investigators).

While at times unbearable to watch (also for the sheer endurance required of one sitting), this is Barney’s most redemptive work to date. In comparison with many of his previous film projects, which can seem like artworld porn, there is a magnificence in the grand narrative and pyrotechnics as scenes of spectacle, and a sense of empowerment experienced through the diverse cast stepping up to enact the role of the gods. Without necessarily understanding all the details, this is one long funeral march for a culture in its patriarchal and industrial death throes, seen out with majesty and absurdity.

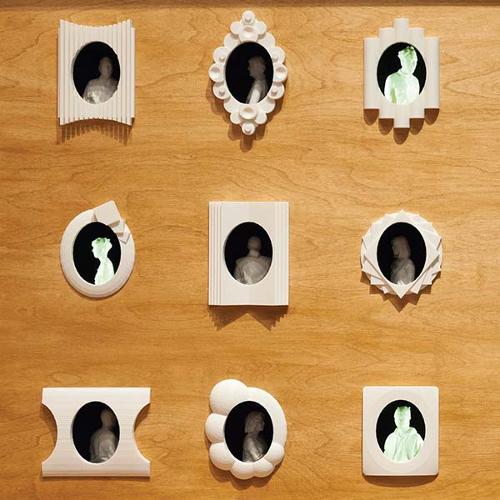

The film (screening as part of Cinemona) is mandatory viewing to understand the work on show. As an exhibition, it is more problematic. The objects from the performance are in this sense given a secondary role as the ‘ashes’ of the art (to quote Yves Klein). Making use of MONA’s collection of Egyptian funereal relics (arranged by the artist as part of the new display), adds a totemic, real-world value to the presentation, not to mention the significance of incorporating genuine human and animal remains. The venue, with its subterranean tomb-like vaults, indeed casts the viewer in the role of archaeologist or tomb robber. Following this logic, in the first room (like the entry chamber), the presentations of ephemera, script and production notes as storyboards in vitrines are given supplementary gravitas by the accompanying friezes and small objects. Proceeding further into the central galleries, we encounter the real bodies and more curious juxtapositions of ancient Egyptian relics and Barney’s own objets d’art, good to go for the afterlife. If their provenance and general existence as museum objects wasn’t already a somewhat questionable accompaniment to contemporary art, these dead Egyptians and their accoutrements are curiously aligned with Barney’s controversial but undeniably fecund vision.

Moving on, what really steals the show are not the human but the car bodies. Reinforcing the central role of the performance are the monumental works of sculpture formed from the radical acts of salvage, wreckage, melting, casting and compaction. Among these, Canopic Chest (2009-11), is a bronze casting of the front-end wreckage (like the organs in the jar) of the Chrysler Imperial. In reverse, as the absent figures of the mould form, Rouge Battery (2014), named after Detroit’s famously toxic river, laced with metals and pollutants, is a bed of gleaming copper and iron that represents the absent hollows of the vehicular body. These are the literal bodies without organs of the industrial era returned to their origins as base metal.

Next to these works the limitations of the theatrical object are perhaps most elegantly revealed in Boat of Ra (2014), made up of the vestiges of Norman Mailer’s attic from the film set. This rooftop frame structure of the mobile apartment, scoured back as fine wood remnants with added bronze ropes and regalia, is like the damaged chariot in Tutankhamen’s tomb, a mere stage prop that is clearly not going anywhere.