This period of reflection on the Anzac Centenary (1914-2014) involves many of us in a fraught relationship to histories of war and remembrance. Indeed, it would be hard to think of a subject that has polarised Australian society more relentlessly than attitudes to both official and unofficial involvement in armed conflict. Anzac Day looms as large in the nation's much-discussed psyche as does our national day, Australia Day. But its agenda of honouring only official Australian armed services and not the impact of war on civilian populations (the role of Remembrance Day) along with the broader humanitarian consequences of global conflict remains an anomaly. For many Australians, with alternative histories and experiences of war, migration and displacement, as for Indigenous peoples whose lives were so drastically impacted by frontier conflict with European settlers (a conflict that many say should be given the status of a war), a broader view of the human landscape would go some way to creating a more inclusive agenda.

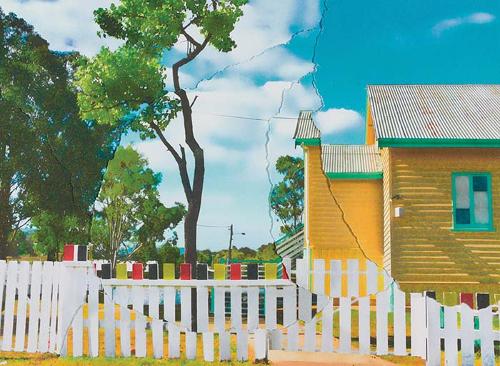

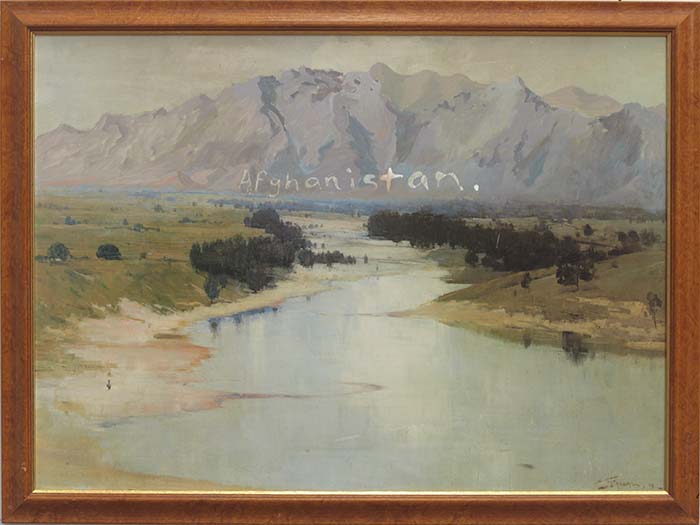

This issue of Artlink (my second as editor) marks the Anzac Centenary with an attempt to put together just such a larger narrative and diverse range of viewpoints. Supporting this, I am grateful to official war artist Ben Quilty for allowing us to reproduce on the cover a detail as focused view from his Transparent Might After Afghanistan, 2011. This provocative work of appropriation from his remarkable touring exhibition After Afghanistan (reviewed in Artlink 33#3) encapsulates the idea, appropriate to this issue, that war creates 'badlands’ around us and within us. In the creation of this work, Quilty has cleverly fused a vision of the mountains of Afghanistan with a ‘found’ painting by Arthur Streeton, Hawkesbury River from 1896, painted the same year Streeton made The Purple Noon’s Transparent Might. Streeton’s title, taken from Percy Bysshe Shelley’s poem ‘Stanzas Written in Dejection, near Naples’ provided an appropriately emotional response to the landscape. It is not hard to see the parallel between Australia’s arid geography and still rugged landscape, with the impenetrable mountains of Afghanistan. Quilty, who grew up on the Hawkesbury, and wandered its banks in the 1990s to locate this particular view of the meandering river, was notably inspired by the mandate of Streeton (also a former war artist) to paint local and familiar subjects that capture the spirit of Australia (most notably its heat and light). These violet hues, as much as they sum up a romantic image of hills in the distance also inspire reflection on Australia as a frontier and site of conflict – our own bloodlands.

Such historicising views and re-enactments are appropriate to introduce an issue that looks broadly at art history, as it informs contemporary cultural experience. As a further example of this, it remains a fact that the single-biggest wave of public art commissions, driven by communities across Australia, are the 13,400 or so memorials erected to honour those who died fighting in the First World War. The subject of photographer Laurence Aberhart’s remarkable ANZAC series (profiled in this issue by Shaune Lakin), these portraits capture the long shadow such monuments cast over public life and shifting attitudes to mourning. Once neglected, more recently restored and resurrected, they are joined by other memorials that add to the roll call. In the build-up to the Anzac Centenary, memorials and memorialisation are sensitive issues to negotiate while life goes on around us, heaping yet more challenges.

In this issue, there are many interesting accounts that take a long view of our short war history, supported by examples of art’s vital role as mediator. For this I am grateful to all the contributors for their considered and complex reflections on a topic of such consequence to our endurance, intelligence and maturity as a nation.