This unassuming yet powerful exhibition curated by Melinda Hinkson marks the 50th anniversary of the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) through a partnership between AIATSIS, the Australian National University and the National Museum of Australia.

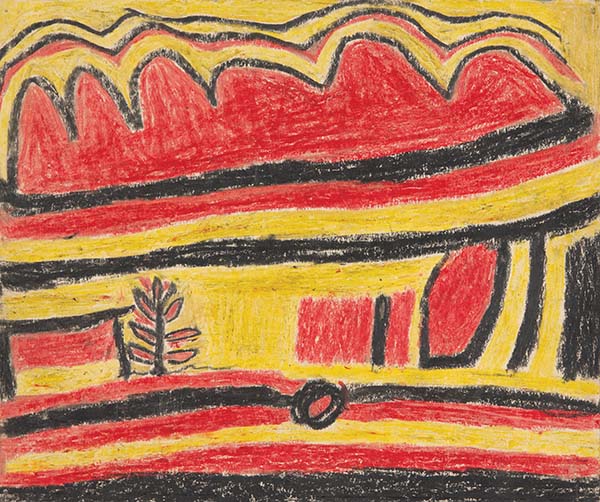

Warlpiri Drawings gives viewers a rare opportunity to see Aboriginal drawings on paper which are seldom exhibited due to their rarity and fragility. It uses drawing as a lens through which to engage with the experience of the Warlpiri people of Lajamanu and Yuendumu from early years of contact with Europeans to 2011. Its starting point was 119 crayon drawings commissioned by anthropologist Mervyn Meggitt and his wife Joan in 1953-54 in Hooker Creek (now called Lajamanu) to document aspects of Warlpiri cosmology.

Hinkson, whose PhD was on the engagement of the Warlpiri people with visual media, learned of the drawings and made them the subject of her postdoctoral research, at first in collaboration with AIATSIS staff member, Stephen Wild, then on her own. This exhibition and its accompanying book published by Aboriginal Studies Press are the result.

Works from other collections of Warlpiri drawings that Hinkson uncovered are included, together with photographs, a film and material culture objects illuminating the works. The crayon drawings and ochre drawings on headbands collected by anthropologist Olive Pink in 1933–34, and drawings collected by manual arts teacher, David Tunley, at Yuendumu from 1967–70 are delightful.

As part of the postdoctoral project, Wild and Hinkson took copies of the original Hooker Creek drawings back to contemporary Warlpiri people in 2011. This repatriation sparked the production of over 200 drawings celebrating people's reconnection with the early works and the relatives who had produced them, as well as remembering aspects both joyous and tragic of Warlpiri history.

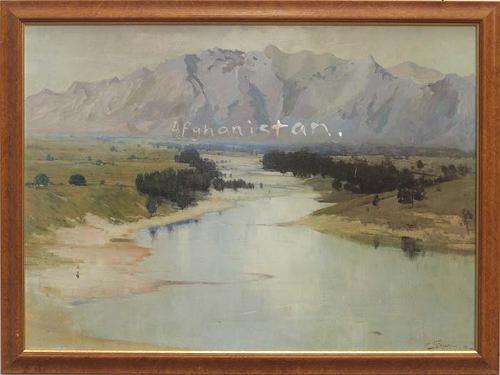

The Meggitt collection includes work by men such as Larry Jungarrayi (Spencer) and Abe Jangala who went on to become leading artists; drawings by women with whom Joan Meggitt worked, as well as drawings by younger men. These provide valuable art historical insights into Warlpiri modes of representation. The subject matter of these drawings ranges from Dreamings; malevolent spirits; more secular views of country; to European Australian material culture and technology.

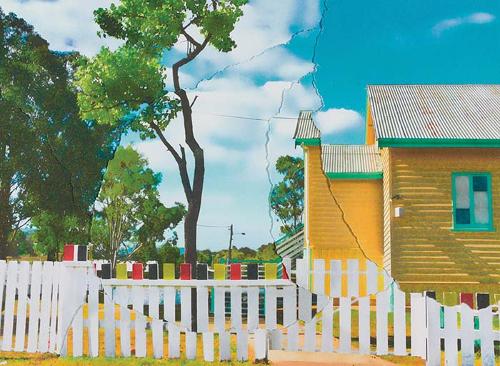

The drawings collected by Tunley and those produced in 2011 by adults and children of Lajamanu and Yuendumu extend the cross-cultural reach of the exhibition by their use of single point perspective representation and watercolour as well as traditional aerial perspective. The wonderful drawings of the 1969 American landing on the moon are not to be missed.

Warlpiri Drawings and its accompanying book are rewarding at many levels. Hinkson’s treatment of cross-cultural representation, of conflict and conflict resolution between Warlpiri and between Warlpiri and European Australians is both nuanced and courageous. The collaboration of Hinkson and Wild with contemporary Warlpiri, and a range of other scholars, has enriched the interpretation of the historical drawings and brought a valuable new collection of drawings into being.