Christian Thompson's show at the Australian Centre for Photography, Mystic Renegade: The Promise of Returnis a tightly realised and strikingly beautiful lament for lost cultures, and languages. There’s a strange, quiet fury to these carefully considered images. The malevolent spirit figures in the triptych Trinity literally seethe smoke, and the haunting refrains of Thompson’s voice in the video work Refuge, singing in the recently extinct Aboriginal language Bidjara, can be heard throughout the space. It becomes an almost funereal, otherworldly soundtrack to the whole viewing experience.

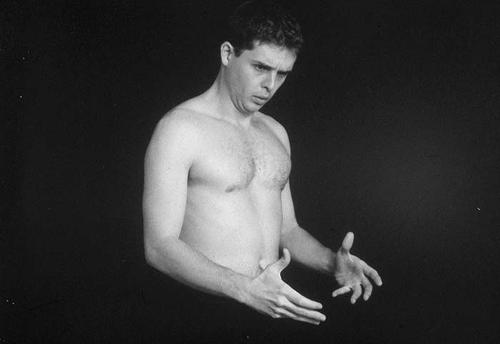

Thompson has long been interested in cultural fragmentation and here he weaves mandala-like images of Bidjara text in the series Eight Limbs with photographs from his Polariseries. These include the aforementioned Trinity portraits, with Thompson as mystic and model, and photographs of broken crystal pyres, their titles - Siren and Ariel – also ripe with mythological references.

An underground language, Polari emerged in Britain between the 1930s and 1970s from the slang of travellers, thieves and beggars. It was later appropriated by British gay sub-culture as a way to communicate safely in an era when homosexuality was a punishable crime.

As with all Thompson’s work, these titles add a nuanced layer to our understanding of what is being communicated here and of the scale of things lost and misunderstood. Thompson breathes life and spirit into these lost languages and in some strange, mystical sense, the works seem to promise, or threaten even, a resurrection of sorts in the wake of their loss. But, in the meantime, we’re just left to mythologise them.

Also on show at ACP is a group photomedia exhibition, curated by

Claire Monneraye. Dear Sylviabrings together the work of nine international women artists whose subject matter is the representation of the female form as both literal subject and social construct. Sylvia is of course a reference to Sylvia Plath.

As a collection of work that includes documentary portraits, contemporary photography and video, there is a total avoidance of cliché here as these women intimately, unapologetically and often humorously examine and author their own understandings of women – their bodies, their rituals, their politics and their relationships.

Dutch photographer Marlous van de Sloot, in her series Le Corps Vécu takes a visceral but slick look at ideas of sensory perception and corporeality. In Likjsje (2009) the sugary ice-creamy goodness of the Paddle Pop is replaced with a sloppy tongue, while in Sarah (2012) the nipple becomes a rubber pacifier.

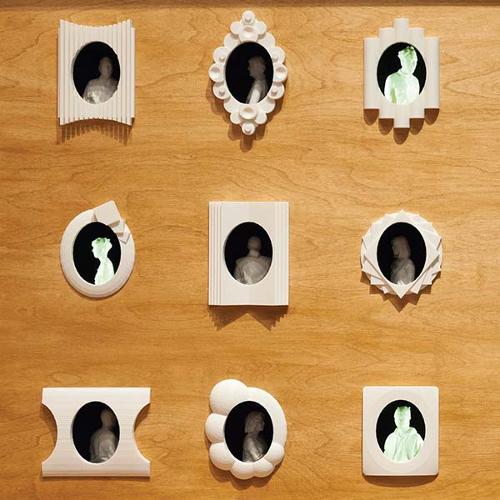

Elsewhere, British photographer Polly Penrose in A Body of Work (2001–14) tries wittily and doggedly to jam her body in amid the hard edges and corners of conference tables, stairwells and chairs. Other highlights include Alma Hasser’s Cosmic Surgery series, melding origami and portraiture to create disturbing portraits that suggest a kaleidoscopic state of mind, and Dina Litovsky’s Bachelorette series exploring the rites of passage and social performances that exist in the public and private spaces of women’s lives.

Reflecting on these two quite different exhibitions, the lasting impression really is of ACP’s strong curatorial programming. Both shows are worth experiencing.