More than a century has passed since the Heidelberg era and nearly 90% of Australians now live in urban areas yet a rural way of life still seems intrinsic to our national identity. Emerging independent curator, Anna Louise Richardson, notes that this persistence of the pastoral in our culture is often dismissed by urbanites as nostalgia, an assertion she contests through her recent project, Worth its Weight in Gold.

Almost all of the artists in the exhibition have worked or lived on family-run sheep farms, some still do. The arrangement of their works in Moana Project Space was almost theatrical. A long dining table, adorned with three bronze centerpieces, stood in the centre of the room. A hall table was placed against one wall, on others hung portraits, a framed certificate and a kitsch barometer. At first, the works seemed to collectively present a coherent exploration of the material environment of a working sheep farm and the characters one may encounter, as well as the results of their labour: wool and meat. However, discordant contradictions and internal tensions soon became apparent.

In the corner of the room, two matte black, life-sized fibreglass and resin figures, easily identified as farmers by their Akubra hats, were locked in an embrace. Disconcertingly they were the same man, one resting his head on the shoulder of the other. They seemed to be comforting each other in an embrace that was both intimate and awkward, an exquisite depiction by Geoff Overheu of how defeat and disappointment in thinly populated farming districts are often borne alone.

The kitsch barometer was festooned with neon jellybeans and an ear tag. A picture frame on the shelf below showed a grainy video of a man skinning and gutting a carcass. The elements of Paul Caporn's unsettling installation appeared unrelated but resembled a jumbled cluster of remembered sights from childhood visits to a farm.

Nearby, the certificate and a brochure cheerfully explained Roderick Sprigg’s offer of a chance for viewers to foster one of three orphaned lambs. Foster carers needed to name their lamb, then make decisions about where it should be raised and whether or not it should be mulesed. Nearby a wall-mounted, mirror backed kitchen drawer full of wool reminded anyone who contemplated the offer of the potential pull between caring for the lamb and its monetary value.

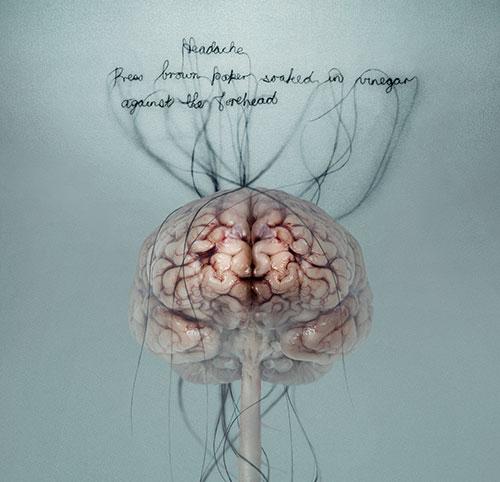

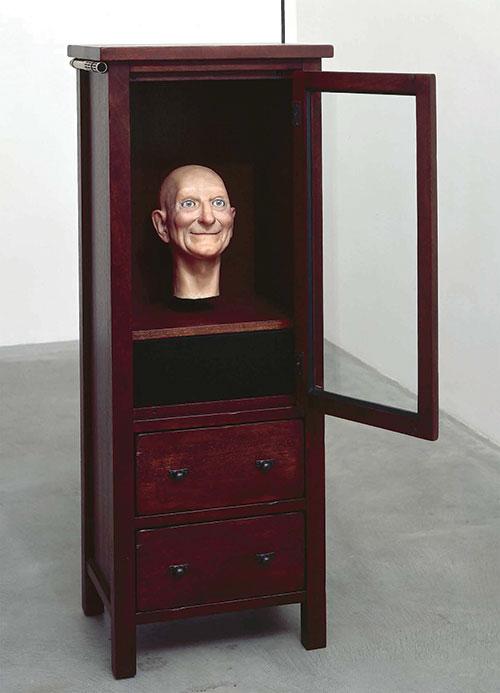

On wall-mounted coolroom shelves were what seemed to be five skinned sheep heads in plastic bags. Waiting for Dad (2011) was Abdul-Rahman Abdullah’s homage to his father’s routine task of slaughtering sheep to feed the family. This practice, whilst in keeping with their Muslim heritage, was undoubtedly unusual in suburban Perth in the 1980s. In this case, these shockingly realistic tinted silicone constructions refer to an episode in which the artist’s father was unexpectedly detained overseas, resulting in only heads being left to eat until his return.

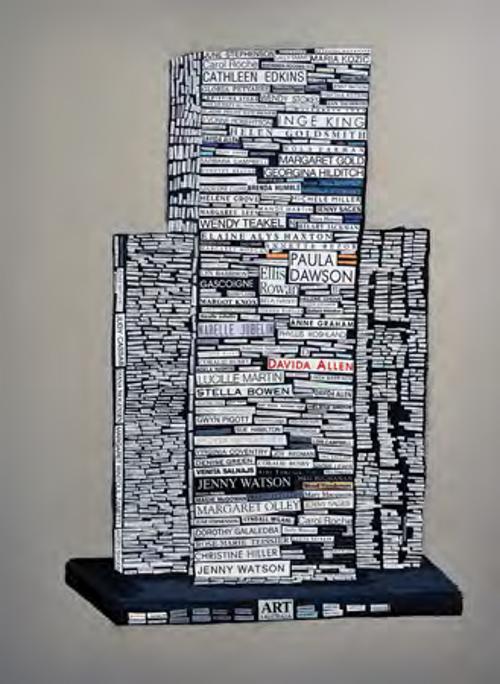

Seven full-length portraits of shearers, executed by Richardson on sheets of HardieFlex, were propped against the far wall. Inspired by childhood recollections of the annual appearance of the shearing team at home, Richardson arranged to photograph a team during smoko break at a nearby shearing shed. The portraits perfectly convey the awkwardness experienced by these work-toughened characters as they briefly entered the unfamiliar realm of art in the role of artist’s models. Interestingly, in the role of artist with a team she didn’t know, Richardson felt similarly out of place in their domain.

The curator strove to bring the realms of agriculture and art together in three invitation-only events held in the exhibition space. These featured a shared meal and talks by selected artists, farmers and other experts on sheep at Megan Christie’s dining table. The Wool Table (2014) is made from the timber from an old wool-sorting table and parts of the floor and uprights of the artist’s own shearing shed. Suspended above the table were a pair of wall pieces by Valdene Buckley-Diprose who formed handspun and knitted wool over corrugated iron until it adopted its profile.

Many of the artworks in the exhibition were simultaneously authentic and nostalgic. The visual language of a farming environment has been co-opted to articulate Australia’s rural past to such an extent that it is almost impossible to work with an Akubra, corrugated iron or a wool-sorting table without embodying nostalgia. However, the artists who commandeered it here were able to surpass sentimentality to present complex, idiosyncratic accounts of rural Australia.