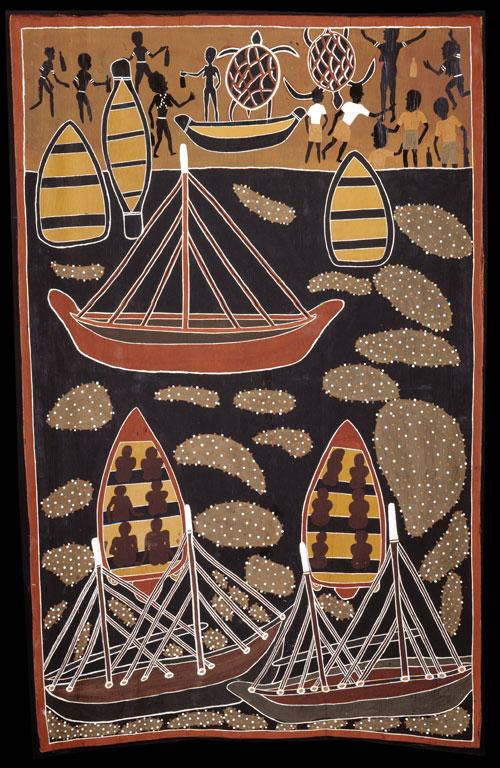

The remarkable achievements of Australia’s great bark artists have often been eclipsed by the meteoric rise of the Western Desert movement spear-headed by the artists of Papunya Tula in the early 1970s. Old Masters is one step towards redressing this imbalance. Three leaders in the field of Aboriginal art and culture were involved, with Howard Morphy and Luke Taylor selecting the images — and Wally Caruana participating as the consultant curator. The paintings were chosen from 2,000 works in the national ethnographic collection held by the National Museum of Australia. The final result is an exhibition of one hundred and twenty works produced between 1948 and 1988. Amongst the forty artists selected from west, central and eastern Arnhem Land are such prominent figures as David Malangi (responsible for the work on the one dollar note), Yirawala, Bardayal Nadjamerrek and Narritjin Maymuru.

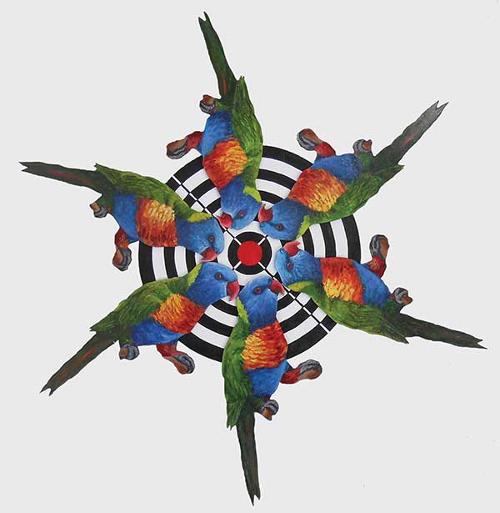

Within Old Masters wallpanels and section titles draw upon a vocabulary from Western art history which acts to emphasise the high status and aesthetic achievements of the artists selected. One section of the show is devoted to the ‘school’ of Yirawala thereby suggesting that, like the school of Rembrandt, this ‘old master’ handed down artistic traditions to future generations of painters. Howard Morphy explains in the informative catalogue accompanying the exhibition that the utilisation of the term ‘old master’ in relation to these artists is “deliberately provocative. Implicitly it places the bark painters of Arnhem Land within the frame of European art history, moving artists away from the religious and ceremonial context of artistic production.”

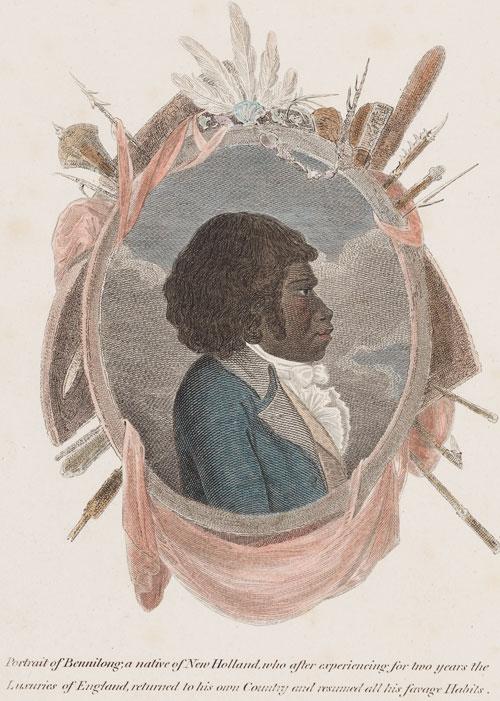

This approach provides us with glimpses of yolngu/bininj (two different language groups in Arnhem Land) world views which in turn act upon us to challenge and broaden definitions of traditional Western concepts such as ‘abstraction’ or ‘the portrait’. Hence the portrait section in Old Masters features two works that display Harry Makarrwala and Jimmy Wululu’s clan designs rather than realist representations.

This is one of the few exhibitions of Australian Aboriginal art I have seen that achieves a reasonable balance between the provision of information to allow a viewer unfamiliar with the works some insight into their significance whilst also allowing for their aesthetic appreciation within a space uncluttered by intrusive interpretive texts, lurid lighting or multi-media displays.

As well as detailed text panels, catalogues are available for reference within the exhibition along with a set of carefully selected films that give the viewer an insight into the processes behind the creation of the works – and their links with body painting and ceremonial dance, a theme that NMA curator Alissa Duff takes up in her catalogue essay. The lighting and placement of the works in clear sections on coloured walls that echo their ochre palettes is deliberately designed to allow for an aesthetic appreciation of the bark paintings.

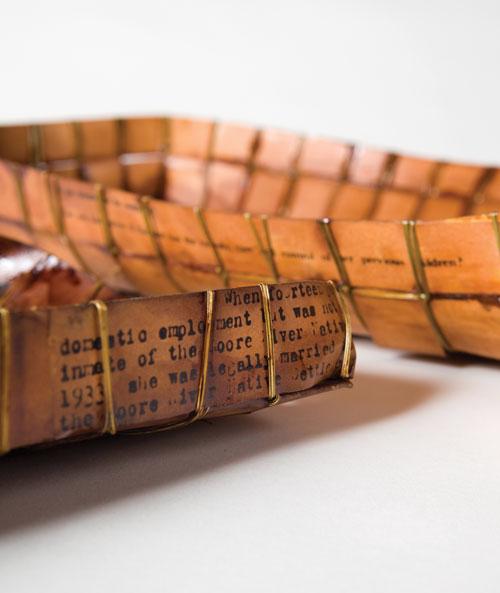

Old Masters also emphasises how artists such as Yirawala utilised bark painting as a way of providing a bridge between two cultures – teaching Balanda (non-indigenous people) about kinship and connection to country. Some of these artists were actively involved with such initiatives as The Yirrkala Church Panels (1963), The Aboriginal Bark Petition (1963) and The Aboriginal Memorial (1988).

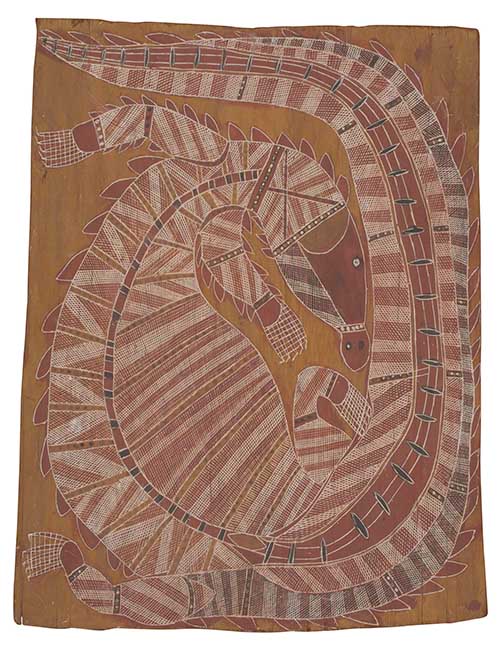

The show reveals the genealogies between different generations of artists detailing how Djon Mawurndjul, one of the most well-known of today’s contemporary bark painters, continued a tradition handed down to him by his Uncle Peter Marralwanga who was himself taught by his uncle Yirawala. Striking works include the Rurratjingu Mortuary Ceremony by Mathaman Marika in which “the rays of the sun capture dust rising from the ground as people dance in the ceremony depicted below”. Then there is Mawalan Marika’s painting Sydney from the Air produced following his first visit to the city in 1963, Yirawala’s iconic representation of Ngalyod Rainbow Serpent, and Jack Wunuwun’s beautifully rendered Bartji (Jungle Yams).

This is a sophisticated show that requires extensive amounts of time to fully process and absorb – the artworks themselves and the theoretical context presented within this exhibition. Ultimately, the viewer is invited to begin to comprehend yolngu/bininj ways of viewing, seeing and experiencing the world, ways that involve family, kinship structures, moieties, stories of creation, metaphors, visual puns, clan designs, ceremonial practices, philosophical views of the world, and stories detailing clan connection to country.

It is to be hoped that this landmark exhibition will succeed in giving a higher profile to both the artists themselves and the National Museum of Australia’s internationally significant collection of bark paintings.