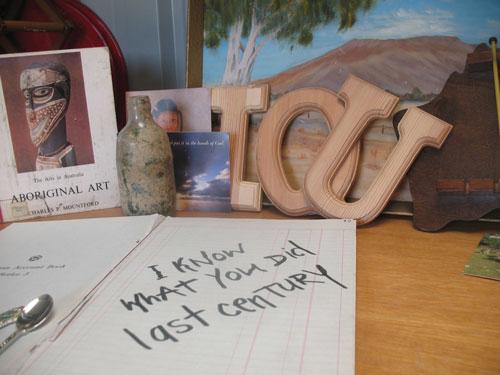

During the early second settlement of Australia, anthropologists, artists, and officials of the Crown photographed Aboriginal people, usually without consent, payment, or proper acknowledgement of the subject. The images are confronting, shocking, exploitative. Amongst the initial images, Aboriginal people are portrayed as uncivilised, undignified, and savage.

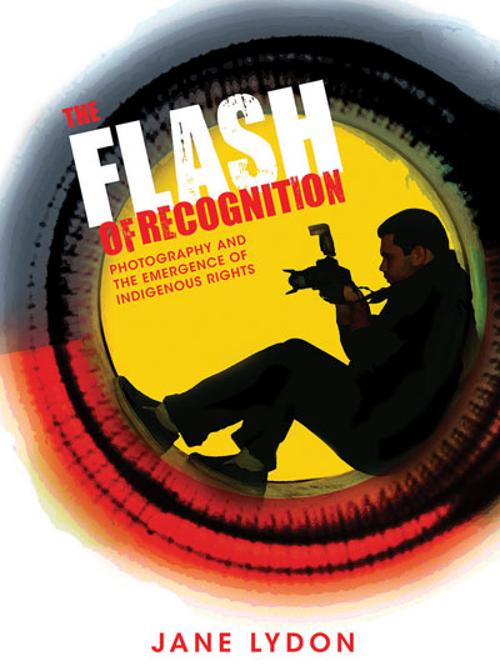

Jane Lydon begins by reflecting on some of these early photographs — Aboriginal people held as prisoners with manacles around their necks, wrists, and ankles. Her reflections are brought to focus with interpretations of three artefacts: an early photograph of neck-chained Aboriginal men published on the cover of a book from 1970; a collaborative artist/community painted mural from the mid-1980s that appropriates a similar photograph; and an image from the 2008 documentary film First Australians that shows a dozen Aboriginal men in slavery. Through a discussion of these artefacts, the author introduces the power of these images as symbols of Aboriginal injustice. The images continue to confront and continue to be a resource for publication and inspiration in a range of media.

The question of why the invaders documented the possession of the country’s Indigenous inhabitants is not pursued. Even with the passing of time it is difficult to understand how photographic documentation could be used for justification of such unjust practices. Perhaps the pursuit is an indicator of the British Empire’s then strategy to denigrate the Indigenous peoples whose lands they were taking.

Lydon’s research reveals that throughout history images of Aboriginal people have served to demoralise them, yet the very same imagery that shows the disparity of social conditions between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australia has been deployed as powerful visual material for campaigns to bring about social change and advocacy for the human rights of Aboriginal people.

The book focuses on the photographic imagery of Aboriginal people in Australian newspapers at the turn of the twentieth century. It examines the development of visual strategies that were employed through journalistic media during the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s to bring about new forms of activism that demanded equal rights and recognition. It is a reminder of the power of mass media to be both a reflection of social sentiment and a catalyst for national transformation. To unpack the ways in which Aboriginal subjects have been portrayed, the book’s analysis engages with critical discourse, combining literature review, photography theory, ideologies of racism, nationalism, politics and moments of insight.

There is a strong threading of history throughout the book. The author draws on collated material from occurrences in linear time and various locations throughout Australia, recognising that activism advancing the plight of Aboriginal people occurred nation-wide, not only in Sydney (generally regarded as the centre of the Australian civil rights movement).

It was pleasing to see Mervyn Bishop is acknowledged for his work as the first Aboriginal person to work as a professional photojournalist. Bishop was employed at the Sydney Morning Herald for 11 years, beginning with a cadetship in 1963. He underwent formal training in photography, received the News Photographer of the Year Award in 1971, and worked for the Department of Aboriginal Affairs in Canberra where he covered developments in Aboriginal communities throughout the nation. From this work, he created the iconic image from 1975 of Gough Whitlam pouring desert sand into the palm of Vincent Lingiari’s hand. Several images of Bishop’s work are included in the book as well as biographical information, selected interviews, and analysis regarding the impact of his important contribution to photojournalism and his influence on the “self-consciously Indigenous photography movement” that emerged in the 1980s.

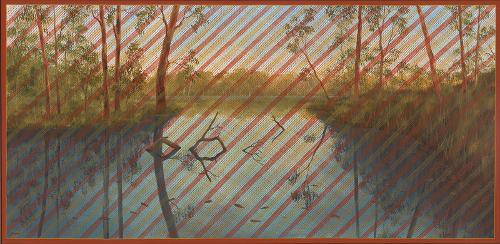

The fourth quarter of the book looks at how the work of Aboriginal artists has either responded directly to or subverted the legacy of the photography of Aboriginal people as an instrument of disempowerment and misrepresentation. Artists have created and published their own photographic images to tell their own stories and re-present Aboriginal people from an Aboriginal perspective.

A number of images included from the 1980s can be read as both art and independent photojournalism. These include some of Brenda L. Croft’s images of Aboriginal people living and rallying in Redfern, Sydney; photographs created by Michael Aird that document Aboriginal people protesting for social justice in Brisbane and an image by Peter Yanada McKenzie at La Perouse, Sydney, that records a demonstration at the initial site of the British invasion opposing the notion of celebrating the 1988 Bicentenary. Tracey Moffatt, who also emerged in the 1980s photography movement, is represented with a provocative ‘photographic performance’ that depicts actor David Gulpilil posed at Bondi Beach in a stereotypical Aussie sunbather pose, subverting representations of both Australian nationalism and Aboriginality.

Other contemporary Aboriginal photographers including Ricky Maynard, Brook Andrew and Jason Wing are represented in the publication with images and text, demonstrating how Aboriginal artists have been pursuing photographic media in diverse and highly political ways.

The Flash of Recognition: Photography and the Emergence of Indigenous Rights should be regarded as a crucial text for visual communication, media, film, and photography scholars, who will learn to be more analytical of how images, particularly images of Aboriginal people, have been constructed through journalism, activism, and art.