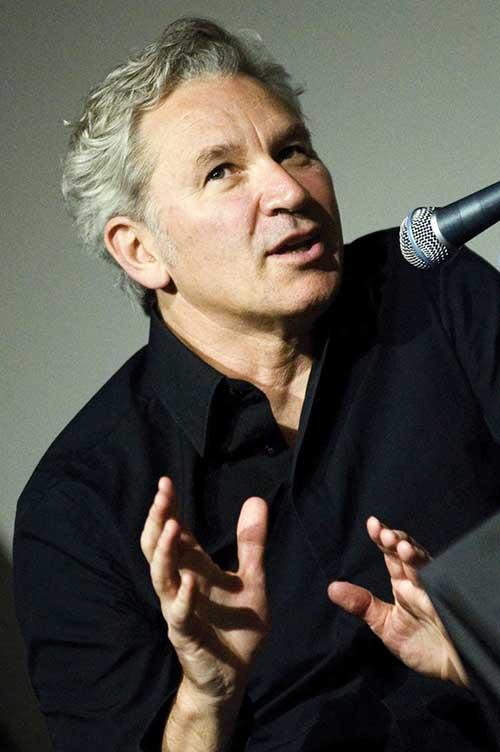

The arrival of The Prince at the Griffith University Art Gallery was not without its fair share of flamboyance. Fresh from the heritage-rich expanses of Central Queensland, Michael Zavros’ much anticipated exhibition, at a cursory glance, promises viewers a nostalgic rendezvous with frontier mythology in a perfectly rendered image of the hunky Western cowboy. Walking a little further into the gallery however, reveals something far from the strong and steady M.O. of the rustic Marlboro man.

Zavros’ interest in fashion and pop culture, photography and advertising is well documented. By thrusting his meticulous series of carefully cropped miniatures in Suit Suite (2000) and large scale memento mori paintings from the Interiors (2011) series into the mix, the curators of this exhibition, Tracey Cooper-Lavery and Diane Warnes, invite us to look again. A self-proclaimed social observer, the artist’s bravura handling of materials often speaks louder than the content of the works themselves. Perhaps the outwardly brutish but carefully styled man in these paintings – so fastidiously crafted, represents not what we have come to associate as part of the fabric of Queensland’s outback identity, but rather, the intense and precarious vulnerability associated with the male ego and young manhood.

So who is The Prince? Younger generations would be let off easily for assuming Zavros as the obvious bidder but it seems that somewhere amidst the lineage of appropriation, or, as Cooper-Lavery poses ‘‘a copy (Zavros’ painting) of a copy (the reproduction of a book) of a copy (Richard Prince’s re- photograph) of a copy (the staged photograph for Marlboro)’’, the answer to this question becomes secondary to a larger one: The Prince of what? This exhibition showcases the artist’s profound ability to take paint and charcoal beyond the realms of possibility. Despite his mastery of the brush, Zavros’ early training as a printmaker shines through in an acute sensitivity to surface, repetition and scale.

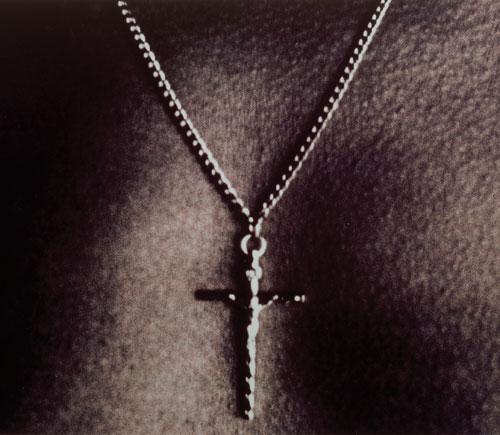

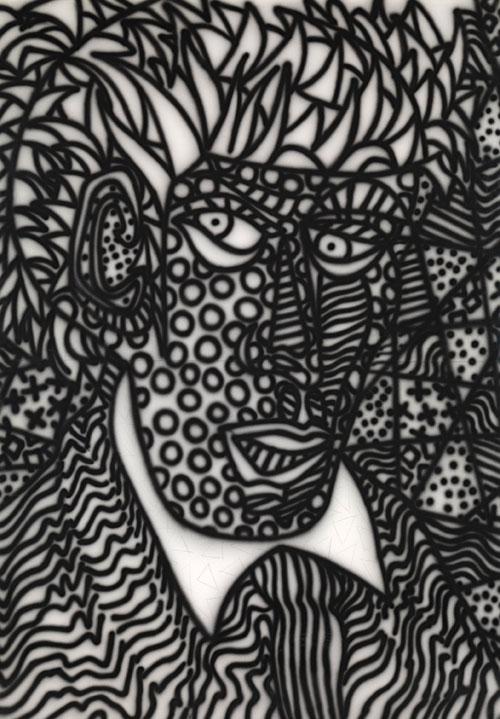

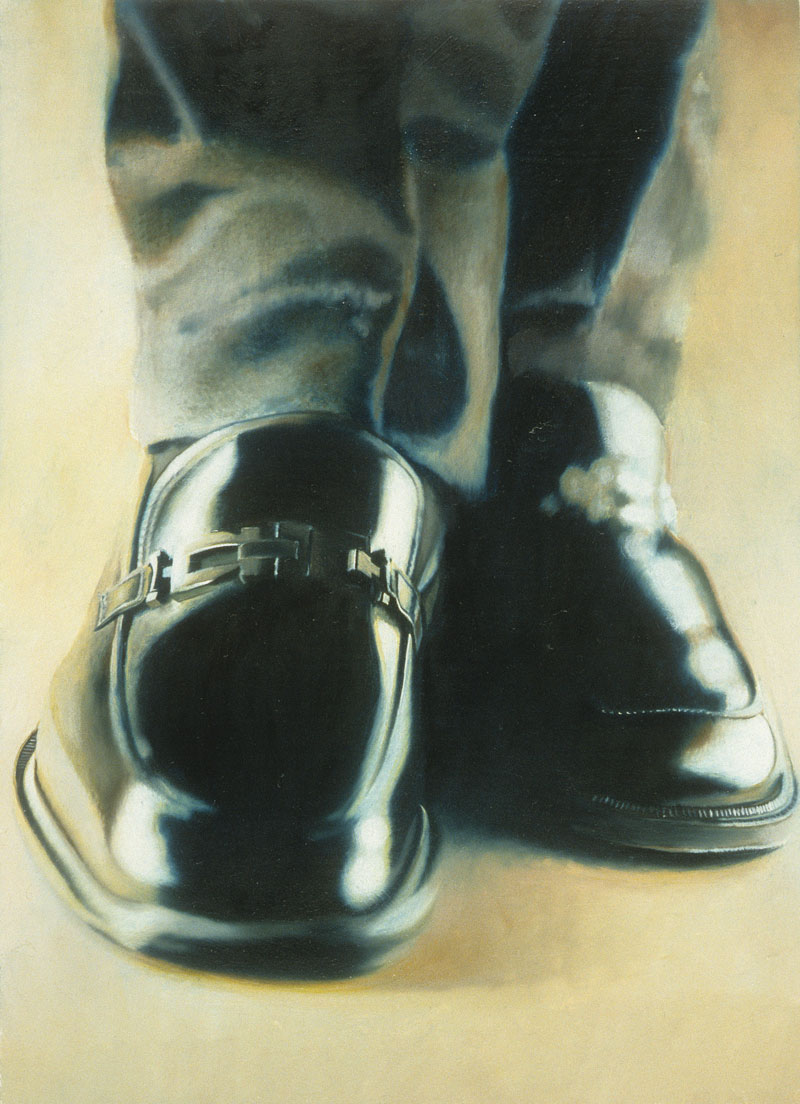

In Ferragamo (2000), the artist simultaneously inflates and offsets typical characteristics of the machismo by exquisitely casting a pair of glossy, high-end men’s shoes on a canvas measuring no more than 15 x 20 cm. Similarly, charcoal works on paper using seductive blacks, such as Prince/ Zavros 11 (2012) allow us to view the Marlboro Man’s rugged masculinity through the most delicate of mediums. While the design aesthetic and notions of perfection (or perhaps, its impossibility) emerge as recurring themes in the artist’s broader oeuvre, traces of various printmaking processes are apparent. Interestingly, Zavros’ ever so subtle echoes to editioning and inexplicable connections to surface and paper – features which have tended to relegate printmaking to an inferior status in the history of art – add a vital layer of bespoke detail and arguably, criticality, to the Prince/ Zavros series.

Admittedly the critical content of Zavros’ work has been called into question before, and much of the hype surrounding the exhibition’s opening made the experience of seeing the show itself seem almost too predictable. What is unknown however, is the extent to which conceptual ambiguity in Zavros’ work is deliberate, and whether the Prince/ Zavros series will, in time, crystallise any speculation on the artist’s critical intent. In his own words, Zavros explains: “I like that what’s seen is so completely different for each viewer and there’s no right or wrong way to look at art ... I was so disappointed by (the) overtly didactic, critical or subversive”. Clearly the artist is willing to give nothing away just yet, smoothly stating: “I just pick the ones that I think are beautiful”. In any case, a psychological enmeshing of power and success is evident in the subjects the artist chooses for each of the series.

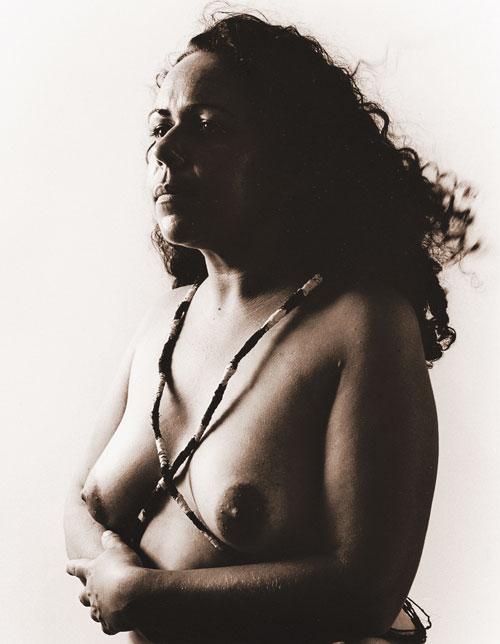

Zavros’ relentless commitment to perfection adds yet another layer to the idea of aesthetics, and holds the notion of a potential Everyman to ransom. The artist uses our own cultural narcissism as a powerful weapon with which to simultaneously rope us in and shoot us down. In an era where narcissistic personality traits are rising at the same rate as obesity and, in the words of artist and writer Pat Hoffie: “the faux-glamour flawlessness of Facebook ‘selfies’ allow even the most average among us to believe in our own self-managed, self-promoted stardom”, Zavros’ work serves as a reminder that we are all ultimately responsible for our own eventual demise.