Humanity seems to be on the brink of annihilating the natural world on which we depend. Our quarrelsome species has built a gigantic web of capitalism, connecting global corporations, consumerism, the markets, the military, rhetoric machines called politicians and the organisations and institutions that now include, tragically, the universities. The rules are set, points must be scored, the different must be taken out, advantage grasped, borders secured, seafood and steak must be on the dinner table. And on the lunch table. We must have aircon and nuclear power. Big cars, new shoes. Any human who fails to enter this race is dismissed as a failure.

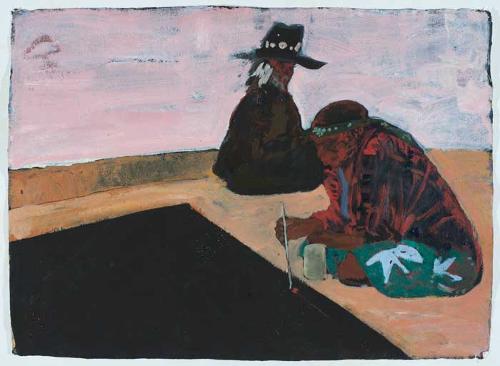

Five thousand years ago Chinese society produced the hermit, a sub-group that recognised the majority tendency of the time and made a decision to opt out. Some took a piece of wood with strings attached to it into a cave, and played sounds which they said were the wind, the water and the mist, or the birds. Hermits were recognised for thousands of years by the majority as a necessary reminder of human excess. Today the Qin is still played by the occasional research fellow, to those who would remember the simple fact that the only things on the planet that have any real meaning are the wind, the water and the mist – and the birds.

Several people have noted in this issue that when faced with a monumental disaster, artists find it almost impossible to make art about it. Doris McIlwain explains the human response that allows us to partition our brain and keep the bits we can’t face in a separate ‘nested’ space so as to allow us to continue with business as usual. She writes of how Ken and Julia Yonetani were so disturbed by the Fukushima disaster that they have found a way of invoking its insidious danger in radioactive glass.[1]

The cave of today may be a place where artists are now lurking, with their own versions of bits of wood and string. But they have started to emerge from the cave and their voices are being heard. In Destroyed Letter, Santiago Sierra has built the word for Kapital, letter by letter in various materials, one in each of seven countries starting in 2010, then destroyed each one by fire; K the final letter, went up in smoke on a cold evening in Melbourne on 12 October 2012. He says “My desire is the destruction of capitalism because it’s [a] criminal system that is putting humankind on the border of extinction.”

Ai Wei Wei became very unpopular with the Chinese government by drawing attention to the shoddy building of the schools that collapsed in the great Sichuan earthquake of 2008 with his piece Remembering in which 9,000 children’s backpacks were arranged on the façade of the Haus der Kunst in Munich. In a lo-tech but memorable event, European eco-artists HeHe (Helen Evans and Heiko Hansen) attracted media attention with their miniature version of BP’s doomed Deep Horizon oil-rig, in which eleven people died and 4.9 million barrels of oil were released into the Gulf of Mexico. In darkness and to the unnerving sound of claxons, the model was exploded using fireworks, and sank in a small lake in flames as part of the Cambridge Science Festival.[2] There are groups of artists working with scientists in the USA and Canada documenting the grotesque mutations being seen in prawns and crabs believed to be caused by the dispersant chemicals used to clean up the worst oil disaster in history.[3] The oil continues to seep from the broken pipe on the sea-bed.

Meanwhile out in the street the people who suddenly have no jobs and nowhere to live are marching against austerity and hedge-funds and bankers and derivatives that have robbed them of the seafood and the steak they enjoyed before. The breaking up of media empires links with the proliferation of information on the state of the planet, which is available to anyone with access to the internet. Every day now, if we choose to look, we can know more and more about the causes of the ends of things in the natural world, just as predicted by Rachel Carson exactly 50 years ago.[4]

It has taken this period of time for governments to show any leadership whatsoever in what looks dreadfully like the endgame of the natural world. The triple disaster of the Great Eastern Japan Earthquake of 2011 that caused the meltdown of the Fukushima nuclear reactors may have caused Big Coal and Big Oil to momentarily overtake Big Uranium. In their terror, Japanese citizens have finally spoken out and forced their government to thwart the plans of the duplicitous energy company Tepco to get the reactors going again. We now have GetUp, Twitter, online petitions, and crowd-sourcing to help call the bullies of the world to account.

The question is how to harness this power to slow down and finally stop the destruction of the natural world by all the umpteen forces that are ranged against it, including farming the wrong crops in the wrong places, acidifying the oceans, using up all the fresh water, destroying forests, pumping carbon into the atmosphere and building nuclear power plants.

Some artists who address the human-induced disasters of our time: the hurricanes, floods, firestorms, broken deepwater oil wells, landslides, melting ice caps, and radiation accidents, display a tendency to become melancholy and elegiac. Hisaharu Motoda has pictured parts of Tokyo, and the Sydney Opera House in ruins, deserted and decayed like many actual precincts in the USA after the sub-prime mortgage meltdowns. Diana Thater has made a video of bands of Przewalskis, the last surviving wild breed of horse, roaming free in the uninhabited forests around Chernobyl, together with other wildlife.[5] Stephanie Valentin shows furniture floating just above the surface of the mirror waters of an Australian river. So plausible yet so improbable. New Zealand photographer David Straight went to Christchurch the day after the 22 February 2012 aftershock which finally destroyed so much of the city, and walked the once tranquil suburban streets, making deadpan records of great lumps of masonry lying rudely on manicured lawns.

Others are part of community groups dedicated to restoring hope to those severely impacted and traumatised. Social trauma caused by war and genocide has a long tail, and Annemarie Kohn discovers that remedies are found in unlikely quarters like break-dancing in Cambodia. Helen Gregory, curator of Floodlines, a community-based exhibition organised by the State Library of Queensland, invited people impacted by the 2010 floods in that state to send in images of their experiences. The result is the Flood and Mosaic Cyclone put together by Jason Nelson and available as an extraordinary online experience.[6]

Others again, such as artists of the lower Hunter, allied with the Lock The Gate campaign, have moved into activist roles, using their skills with imagery and performance to educate and energise the public who in turn can encourage governments to resist the bullying of the obscenely cashed up elites who run the world as their fiefdom.[7]

Many artists and philosophers are immersed in the urgency of the need to take action. From beyond the circles of power and corruption they have consistently called for new imaginings, different perspectives, re-considered options. As Paul Downton says (page 16 this issue) we are living in a war zone. Perhaps these are the new war artists.

Footnotes

- ^ Doris Mcllwain on Ken + Julia Yonetani, Crystal Palace: The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nuclear Nations, Hungary, 2012, p. 28.

- ^ Organised by Invisible Dust, https://invisibledust.com/projects/hehe-is-there-a-horizon-in-the-deep-water.

- ^ http://www.culturebot.net/2012/06/13654/brandon-ballengees-collapse-at-ronald-feldman-gallery/

- ^ Rachel Carson, The Silent Spring, Houghton Mifflin, 1962.

- ^ https://www.hauserwirth.com/hauser-wirth-exhibitions/3667-diana-thater-chernobyl

- ^ http://blogs.slq.qld.gov.au/floodlines/2012/04/03/mosaic-artwork-tells-of-impact/

- ^ The Williams River Valley Artists Project