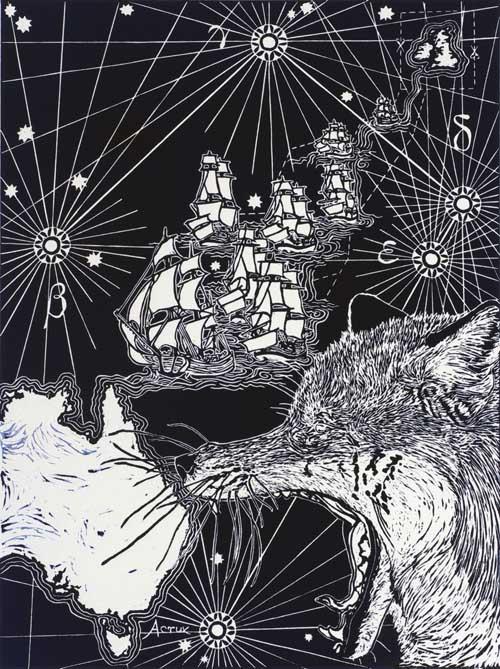

The theme of metamorphosis between all living things, and the pathos of our conjoined destinies, are fully asserted by Berlinde De Bruckyere's work on show at ACCA. I first saw her work at MONA in Hobart where a suspended horse and a human figure in a vitrine showed me something I hadn’t seen before even as they reminded me of many artworks I had seen before - Goya’s war etchings, his Black Paintings, William Blake’s watercolours and monoprints of humans and gods, the many bodies in the work of Hieronymous Bosch, the tormented Christs of countless altarpieces. The father of Belgian artist De Bruckyere was a butcher and she was sent to Catholic boarding school at the age of five. Here, hiding from the nuns, she pored over art history books. It shows. In a particularly European kind of humanism De Bruckyere’s sombre work draws attention to suffering and to flesh, its sentience, vulnerability and mortality.

The artist visited ACCA two and a half years ago and decided that the high ceiling of the large gallery was like a church and the side galleries like chapels. The two works hung in the large gallery are each called We are all Flesh. They look like two dead horses hanging with massive bulk, one from a strap off the wall, the other from a huge lamp-post from the Ukraine brought to Australia by ship. These are revealed on closer inspection to be four horses because each horse is wedded to another horse, not mechanically but clumsily, as if with emotion. Here there is great attentiveness to detail but the work is not about virtuosity, in fact we see stitches and loose threads in the hide of the paler horse of the two sets. And the spines of the horses do not sit straight against their hides as a taxidermist would prepare them, they have slipped, adjusted, moved towards greater knowing or intimacy. The horses are metaphors for human vulnerability and suffering, for war, for pain.

In Gallery 4 sits a work called 019 in which a two hundred year old cupboard from the Belgium Natural History Museum is placed centrally, its watery rippled glass doors open. Inside on the lower shelves are thin pale folded blankets while on the higher shelves sections of about twenty-four rough-barked tree branches are vertically arranged in groupings. As the doors are open it is as if the branches may come out. The longer you stay looking at them the more you see. Each one is covered in wax, and what seems to be all pale creamy wax also includes flecks and bands of colour, some blue, some red or pink. The trees are held up by thin string. Like bodies, dryads, they seem at once stored and escaping, an enigmatic museum display of something which we do not expect to see in a museum.

Wax is a material often used in sculpture in preparatory stages, and in painting there are the slow brushstrokes of encaustic but De Bruckyere uses wax more like the Italian sculptor Medardo Rosso or to some degree as it might be used in a waxworks but much more boldly and expressively. She layers the wax inside a mould in a process involving chance, risk and fragility, elements which are thus transferred into the sensations engendered by the work.

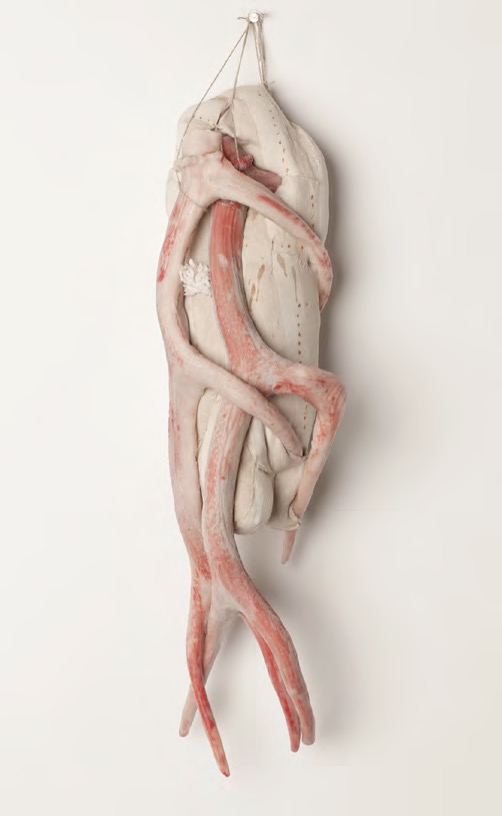

Since first using horses in a work commissioned for the In Flanders Fields Museum at Ypres, De Bruckyere has been asked about using other animals but has not wanted to, though the five Romeu "my dear" works on show, a drawing and four sculptures involving antlers, belie that declaration. The antlers are like intestines or skin that is growing, they twist against each other, wrap into pillows and while, apparently made to register pain, try to avoid it. Another work, Inside me III literally seems to depict intestines yet they are also tree branches, hung in a crib of wood by thin strings, this river of white fleshliness resembles one of Francis Bacon’s tormented gutted figures. The Pillow literally shows the back and leg of a human figure disappearing into a pillow, hiding, twisting.

The four galleries at ACCA devoted to de Bruckyere’s work combine to tell a story of art full of religious intensity. In 2011-12 an exhibition was held at the Kunstmuseum in Bern, Switzerland where De Bruckyere’s work was matched with the paintings of Lucas Cranach and the films of Pier Paolo Pasolini. The tormented figures of these three artists represent important contributions to the depiction of compassion and suffering in European art.