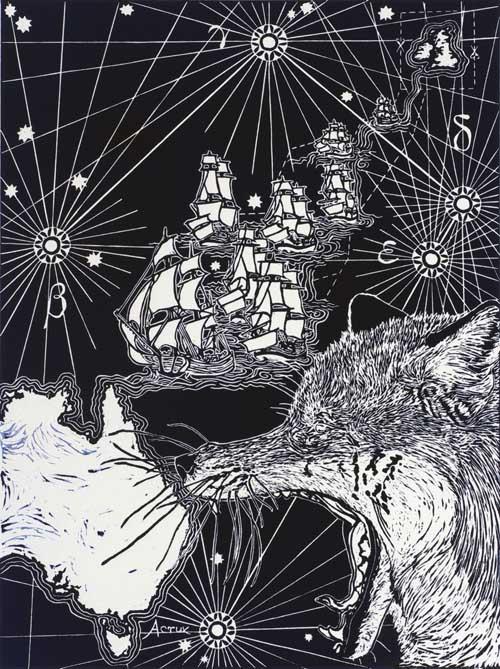

In the baroque garden Karlsaue Park Fiona Hall's punk eco shack is a parody of the local hunter hut typology that reflects the conspicuous consumption and the perverse exoticism of the leisure classes. Pan troglodytes chimpanzee reads Hall’s label for a monkey face of cans holding a phone speared with nails. "Endangered" hybrid species from “equatorial Africa” the label further details with cabinet-of-curiosity-style fantasy. In a carnival of camouflage army costumes are cut up into riffs on painted up corroboree torsos. Interspersed are ghostly pieces of driftwood that shadow this faux Über-nature like rorschachs of totemic animals.

dOCUMENTA (13) is a panoply of potential encounters in which the object becomes a subject and the land, places and things within it enter into a relationship with the viewer. These investigations of the possibility of intersubjectivity between human and nonhuman agents was also the topic of the 33rd CIHA Congress in Nuremberg in July 2012. Simultaneously the 2012 Paris Triennial, curated by Okwui Enwezor at the Palais de Tokyo, explored the French trajectory of contemporary art’s turn to anthropologists of quasi-subjects and quasi-objects (Alfred Gell, Bruno Latour and Michael Taussig). As art history still groans under the growing pains of becoming global the canon of ethnography can be seen to dominate the catalogues of the Paris Triennial, CIHA and dOCUMENTA (13).

Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, the artistic director of dOCUMENTA (13), reflects a move towards less Eurocentric curatorial practice. Her experience from the Castello di Rivoli of making sites resonate through placing objects in exhibition architectures beyond the white cube also suits the comparisons made through adjacencies of sites and subjects at dOCUMENTA (13). Bakargiev brought twelve of the Australian artists she encountered during her time as the director of the 2008 Biennale of Sydney to Kassel. There is a series of Gordon Bennett’s most recent responses to Margaret Preston’s 1930s Home Décor. These are hung, with the work of Emily Carr, a Canadian contemporary of Preston, and around an Anger Workshop by Stuart Ringholt. Even more successful than statements of identity politics, however, is the way Aboriginal dot paintings resonate differently by being exhibited in relation to the historical avant-garde and to global contemporary practices. Though there are German audience members standing around sharing one-liners about the Dreamtime, there are also many looking at the Aboriginal paintings as acts “of being emplaced” through visual perception alone. These same viewers see the triumphant commission of Willie Doherty’s Secretion, a video of the land surrounding Kassel with a narration of a contaminated zone. Secretion could be read as a digital equivalent of the six Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri and five Doreen Reid Nakamarra canvases that are resignified through such instances of “being together separately” in the main venue of the Fridericianum. The paintings’ shimmering plasticity of topographic contours comes to particularly good light in the display that lays them out horizontally. This is an important move as they clearly refer to the ground they are painted on rather than the perspectival tradition of easel painting.

Conceived as the “Brain” of the exhibition, in the Fridericianum there is an emphasis on historic objects that could be seen to power the limbs that spread from it to the other sites around the city of Kassel and of Kabul, Alexandria, and Banff. Among these objects is a landscape by Mohammad Yusuf Asefi, who painted over figures of animals and humans from works that were under threat of destruction in the National Gallery of Kabul. Opposite is a vitrine with objects from Hitler’s apartment including a photo of Lee Miller in Hitler’s bath, posing like one of his neoclassical figures, plus Miller’s eye cut out in Man Ray’s Object to be Destroyed. In the condition of war subject-object relations turn surreal, that is a dOCUMENTA (13) leitmotif. The surreal distortion of the object by the subject is made explicit by the inclusion of Salvador Dali; a surprisingly surreally distorted clock interpolation by Anri Sala; and A drawing to Ms Rosalie Fredeon and her cat Red Oscar, a feminised head of Hitler being devoured in a Kai Althoff drawing.

As you first walk in, a wind (by Ryan Gander) chills the otherwise empty foyer to the “Brain”. Only a handwritten letter to Bakargiev from Kai Althoff is left behind in this first space. You enter the charged absence of an artist on the run, who leaves open the very act of filling space by being on exhibition. Althoff fears he has committed a kind of professional suicide by abdicating from participation in dOCUMENTA (13). He is the subject that resists becoming the object of an exhibit and yet becomes the ultimate tortured artist, which is an object of popular fantasy. His ambivalent being and not being there furthermore affirms both his intimacy with the curator and her ultimate control.

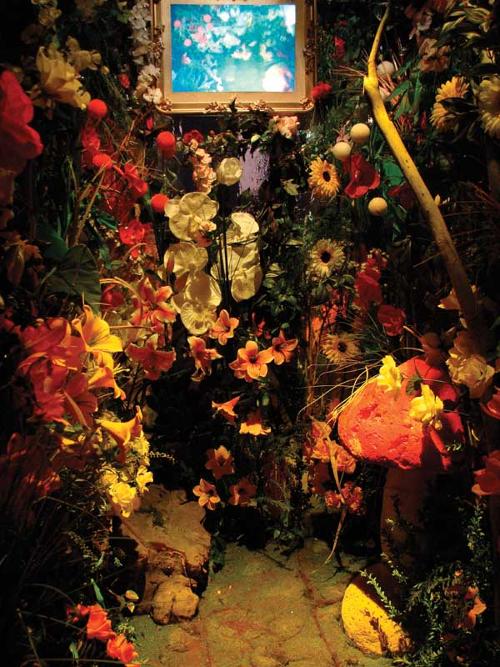

Activation of archives and local sites through the eyes of the artists that are commissioned to make works specifically for dOCUMENTA (13) is the exhibition’s source of coherence and relevance. In Janet Cardiff’s Alter Bahnhof Video Walk an ipod choreographs a thirty-minute piece of physical cinema in which every viewer performs the perspective of the camera roaming through the old train station. The darkness of this central hub of transportation of condemned people that led to the severe bombing of Kassel is doubled by the screen world that leads you through the space. Among Cardiff’s stories is her narration of seeing herself reflected in the train window, overlapped with a stranger. Cardiff’s reflection that “my image mixed with theirs as if we were a part of the same person in a completely separate world” sums up the experiences of intersubjectivity to the fore in this exhibition. The quasi-objects on offer are as varied as critical representations of animal and human rights abuses in homage to Donna Haraway and Fiona Hall’s post-enlightenment Wunderkammer. The effect is a carnivalesque survey of subjects encountering objects under the duress of anger, war, and destruction.