In representing what we know about the world and our place within it, the role of museums has been guided by particular fields of knowledge and power. Visiting a museum consequently comes with a conventional set of practices and ways of seeing that guide us through familiar connections between history, place and culture. Jean-Hubert Martin's Theatre of the World, currently showing at MONA in Hobart, offers a chance to reflect on the limits of these conventions and ultimately move beyond them.

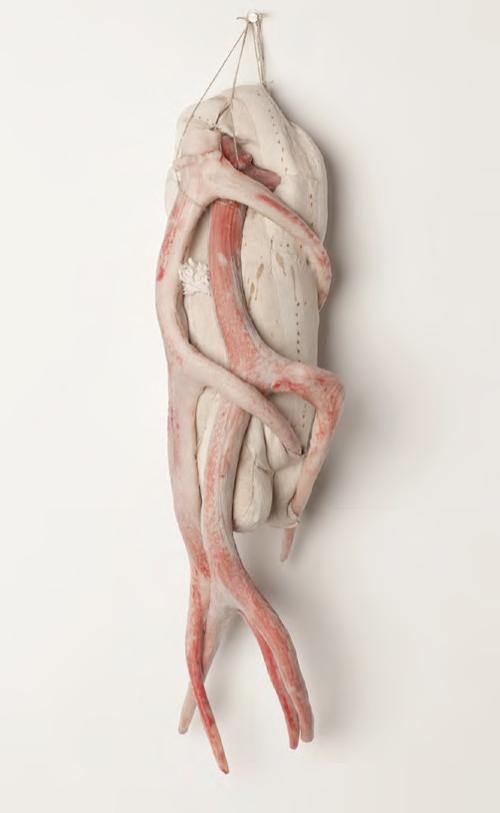

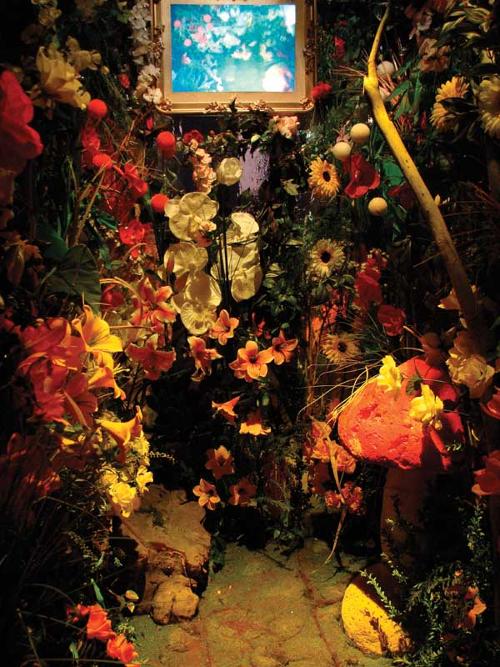

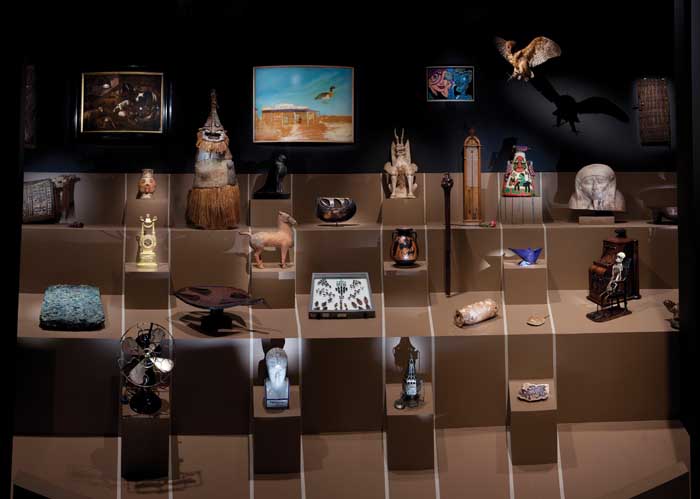

Combining 480 artworks and objects from the public collection of TMAG and David Walsh’s private collection of MONA, Martin has created an exhibition that doesn’t just showcase the wonders of each but provokes a number of dialogues about practices of collecting and viewing. From the introductory wunderkammer-style enclave with its mix of artworks, ancient and modern objects and natural history specimens, Martin offers a series of poetic and aesthetic gestures that proceed by visual association and placement, rather than chronology or classification. The Renaissance concept of the 'theatre of the world’ exists here not in its original form as a frame for knowledge or status but as a space for imaginative processes. The viewer is invited to find mnemonic and intuitive paths through a number of intimate rooms and across a number of different conceptual fields such as ‘phantasm’, ‘corpus’ and ‘civility’.

One of the pleasures of this mode of engagement - what Martin refers to as ‘visual thinking’ – is that you stop to look at things that in traditional museum formats you might otherwise bypass. I found myself absorbed in the connections between the thunder egg specimen, the ancient Chinese tomb guardian and the electric fan, not because they are of particular personal interest, but because of the conceptual play between earth and air. In another room, a Fijian gong looks like a hunk of wood, but coupled with John Coplans’ spliced Self Portrait (1990), it becomes a body part – a gesture on Martin’s part that is both humorous and sombre. Nearby in a colonial bed, the tongue coral sunk into its pillow is a sensuality rendered by poetic association, not marine biology and craftsmanship.

There’s a curatorial magic in suspending this experience from one room to the next that is supported by Tijs Visser’s design. The dark central section of the exhibition weaves a sensitive series of encounters that move from a curved wall of spotlit masks, to the mysterious interior space of Jason Shulman’s Candle Describing A Sphere (2006) to Pat Brassington’s and Dieter Appel’s photographs of exhalations in the corridor before you enter the ‘Beyond’ room of sarcophagi, canopic jars and Damien Hirst’s fly-infested Cholera Seed (2003). This moving sequence conveys the fragility of relations between our organic reality and material culture, and the mediating spaces offered by art to profound effect.

These pleasures are keenly rendered, but there are moments when the mingling of cultural contexts is uneasy. The extraordinary John Dempsey portraits (1820s) opposite Boris Mikhailov’s The Wedding (2005-6) series for example feels abrupt and a little reductive under the header ‘Civility’. And something of the individual beauty of TMAG’s Pacific-region barkcloths was lost for me in the large-scale display, impressive and affective as it is. But, as Martin suggests in his audio commentary, dialogue can lead to conflict as much as to coalescence, and indeed art as a moment of connection is far from being limited to happy encounters. Perhaps this is an effect of sacrificing some parts for the whole.

Theatre of the World is a thoroughly absorbing meditation on the human impulse to materialise our beliefs, desires and fears. Martin’s curation of these two major collections offers many pleasures, not least among which is a sense of regeneration – a chance to reframe our approach to the objects and images we make and collect and to rethink the meanings we attribute to them.