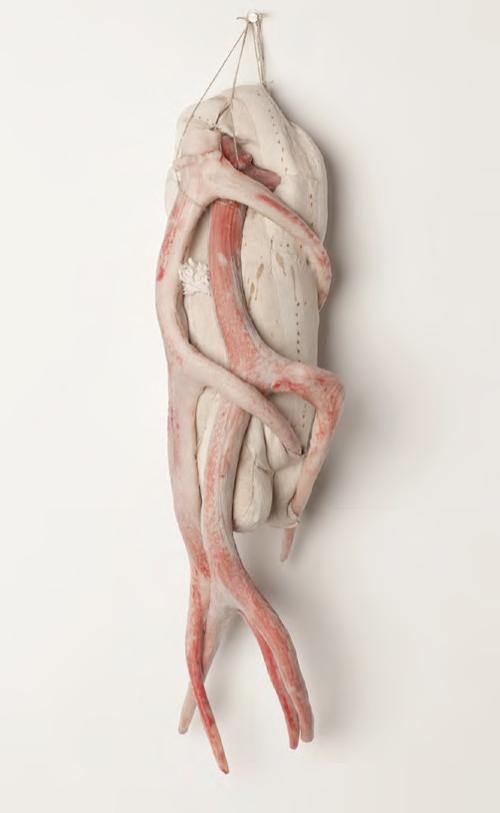

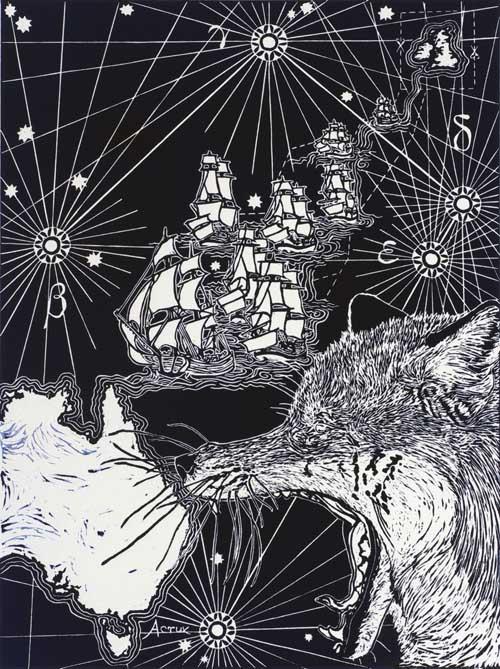

Culturally, we are festering. Most of us know all too well the restless violence that lies coiled under our thin cultural veneer. It emerges as bigotry and racism in its most outward appearance but, insidiously for our cultural development, it is seen in our clawing attempts for international recognition, our belligerent defiance of the first people of this land, and our superficial attempts to appear intellectual. Fortunately, art is one of those areas in life where you can display truth in all its revolting reality and not offend people. Well, not too many at least. Some of my favourite art is the most offensive. It offends me still and that's why I love it: it simply works and no one had to explain it to me. Luckily for you, we’ve not filled this guest issue of Artlink with my own peculiar tastes, but instead conducted something of a survey of recent practices and ideas from younger artists and a few leaders in our field.

This issue looks to ideas of social experiments and collective agency working through new and established models. The art institution model, along with its relative financial and political models, is experiencing tectonic shifts, and yet their representatives remain strangely silent while standing with their backs to the abyss. As organisations scramble to maintain and justify their funding, the catch-cry of 'transparency’ keeps popping up, but that’s just more spin. True change requires agency through a new language that is informed by radical thinking. Yet the way this manifests smacks of subterfuge, diverting the audience’s attention through misleading terminology, pseudo-academic puffery, cut and paste philosophy, or what I call ‘cultural backfilling’. As we know, curators often choose artists or works that fit conveniently into their own creative compositions, yet the voice of the artist is often rendered mute by the machinations of the bureaucracy and the now bulging industry of arts administrators. This has led us to something of an endgame; a disconnect between thinking and doing in contemporary art, whether it’s a million dollar event in a major gallery or an oily rag affair in a dirty carpark.

At the moment, art could be compared to an enormous safety blanket with everyone holding a little piece of the edge, pulling it in their own direction and trying to convince everyone to go their way. Now the problem with this situation is that while we are all busy holding up this blanket, nearly everyone has forgotten why we are holding it. If you look up into the metaphorical sky you can see there are people ready to jump from a figurative towering inferno, a crumbling capitalist nightmare, desperate to leap to safety. If we are to shake off the parochial underpinning of our cultural identity, if we become brave enough as a people to unshackle the coiled serpent lying under the cultural veneer, then we need to be a society where experimentation is necessitated by the right to fail and fail well.