Queensland Art Gallery Foundation Grant

There is a display space on the third level at GoMA which is often inadvertently bypassed by visitors and houses temporary exhibitions from the Collection. Recently it was distinguished by the show Threads: Contemporary Textiles and the Social Fabric. Curated by in-house staff Ruth McDougall (herself a textile artist) with input from Maud Page through her acquisition of fine items from the Pacific region, as well as Russell Storer, a specialist in Asian art, this joyous array of batiks, bags, quilts and garments from Laos, China, Papua, PNG, Hawai'i, Tonga, and elsewhere, persuasively declares the way Queensland Art Gallery has altered its collecting priorities in the wake of the Asia-Pacific Triennial project.

No longer eurocentric in focus, the Collection has also shifted its emphasis away from the traditional artforms of painting, sculpture and works on paper, glassware and ceramics. Instead, 'decorative arts' have been re-imagined and the Gallery now looks to textile and fibre arts that are consciously steeped in narrative and symbology as complex as any 'high art’ figurative painting. That is why the "social fabric" is such an apt and telling subtitle to Threads.

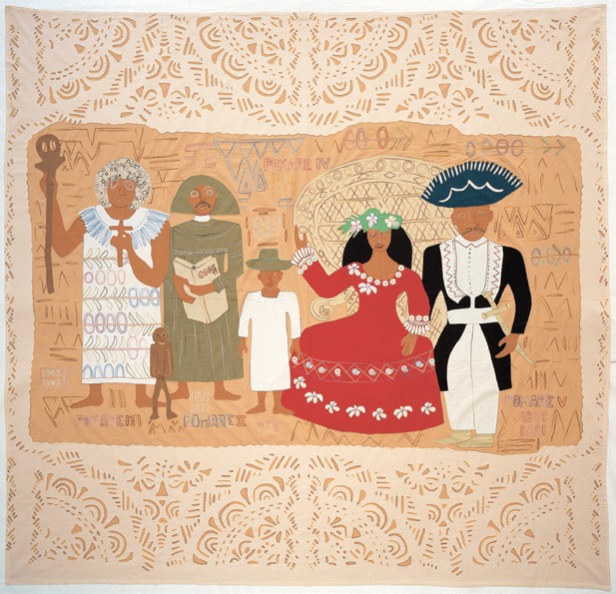

In Threads we are treated to expressive work made chiefly by women (but not exclusively) and often in collaboration with one another. So the solitary tradition of the fine art practitioner is dispensed with and it is possible to imagine both the conversations and long comfortable silences that punctuate the floor, ground, table and loom-based activity of these highly skilled artisans and artists. I am familiar with one from New Zealand, namely Robin White. Originally she made her name as a painter of super-realist landscapes but with time, her Baha’i faith urged a shift to other ways of articulating and sharing her commitment to people and places. From living for some years in Kiribati and producing woodblock prints featuring women she knew and the myths that belong there, followed by woven mats, White has subsequently engaged with other communities, Fiji for example. The artistic products that result no longer bear her name solely and the conventional canvas and paper sheets she once used have now been dispensed with. Instead “woven together” is the nomenclature best describing her current collaboration works with similar-aged Fijian artists Leba Toki and Bale Jione. They produce bark-cloths impregnated with natural dyes that convey simple yet deeply sacred compositions: to live by and be with.

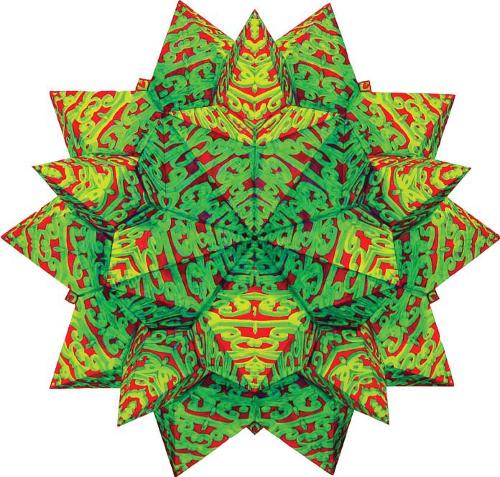

White’s story is but one example that this show reveals out of some thirty or so others. They include the boldly coloured and graphically magnificent kapa kuiki Hawaiian quilts and those from Tahiti suspended from the ceiling of gallery 31, and also the triumphant unfurling of the 22 metre long royal Tongan ngatu tã’uli black barkcloth made in Auckland which links gallery 31 with gallery 32. They include the telling of nationhood and the impact of colonial encounters on indigenous peoples. They are equally about the daily rituals of village life and the belief systems that assist in sustaining them. Both are hugely important themes for Western peoples to appreciate and take on board when envisaging what art history might now comprise. Played out in domestic items that are hand-woven or made from commercial cotton, straddling the incredibly fine tussar silk carrying the intricate and colourful embroidery of Bengal in India, or conveyed through the four hung carpets or kharad of the Meghwal community, or the story-telling cloths of the displaced Hmong peoples from Asia, all are thought-provoking images that repay close attention.

From South Australia, the Ernabella batiks through to the subtle toned bags from Indonesia’s Papua called nokens to the garments based on bilum weaving that make 'wearable art' of great character, Threads refuses to be typecast into any fixed fine art discipline. Furthermore, it includes works from the 1970s through to the present yet nowhere is there the sense of time present or past. It is a steady continuum, even up to the inclusion of Kay Lawrence’s pearl button-encrusted undergarment installation of 2006-08 and Wang Jin’s Robe in clear plastic sheeting embroidered with fishing line, as though amalgamating the ghosts of China’s past emperorship to today’s migrations of peoples and patterns of community re-adjustment and empowerment.