Gallery Central - a striking, elongated space with a soaring ceiling – is the perfect venue to exhibit tall works. Rolls of wallpaper (flocked, embossed, or with geometric patterns), courtesy of Wall Candy Wallpaper, were cut into 4m lengths and distributed to twenty-six invited local artists and designers with the curatorial brief to do whatever they liked, but to retain the original dimensions. The artists' responses were varied and intriguing.

In 'always more steps' Alex Spremberg obliterates a traditional damask pattern with colourful strata of boldly painted stripes. The tension between old and new is wonderfully discordant. The lingering original texture is a reminder of differing penchants for decorating, changing styles, and generations of touch and sound that walls absorb. David Turley’s response to embossed frames on his wallpaper is to feature fragments. Turley, the transformer of unloved objects, has resuscitated a bible by recycling its pages into 'Second-hand Belief'. Cut to fit each frame, the stern intensity of densely printed Catholic pages appears servile, as though choked by white-collared hosts.

In 'The Weeper', Caitlin Yardley responds to the background between vertical bars that reminded her of tears. Interested in how women are described, she has softly pencilled, thousands of times over, a single quote, describing Donatello’s sculptural work 'The Penitent Magdalene' - 'Her hair is red with gold streaks, her skin browned and toughened by the sun. Her sunken eyes stare unfocused, her mind on heavenly things’. Yardley’s mantra 'ad infinitum' on her paper runway of desire is perhaps an idiom shared with the subject of the gaze to escape earthly constraints and is a terrific contrast to Annabel Dixon’s urban airborne blonde in 'CentreFold(s)' who challenges our gaze.

Recently returned from Sweden, where she visited Linnaeus’ house papered with hand-painted botanical images from a book, and intrigued by James Elkins’ 'Pictures and Tears: How a painting can make you cry' Perdita Phillips explores Stendhal’s syndrome in relation to a famous Shinto painting of a woman on a balcony overlooking Nachi Falls. Phillips’ ink painting on the sized reverse side of the wallpaper is a cascading torrent, with a female observer who seems to be at one with the water. As harbinger for protected natural habitats, it is this call to observe the sacredness of outdoor spaces that Paul Uhlmann and Gregory Pryor also pick up on.

Can wallpaper change our mindset? 'Anima mundi', the title of Uhlmann’s work, means ‘world soul’ in Latin and refers to Plato’s concept of the world as a single living entity with intelligence, and in which everything is interconnected. Uhlmann’s response to wallpaper is as material and conceptual interface between home, heart, history and the heavens, a medium through which he can explore environmental ethics. His length of painted sky mouths winged whispers, and breathes life into small beating hearts. Shared air space and the vapours of clouds more than four billion years in the making are something we all share.

Pryor explores the space between a tree’s buds and its litter on the ground. Is it possible to give form to that vertical space and also the state of mind observing trees from below? There is also the space and form of sound, such as delicate soughing and murmuring wind. It is the space of being present in the moment which Pryor seeks to give form. Hanging ever so delicately from a flowering branch in 'Grevillea nematophylla (pillow of wind)' is an elongated, ubiquitous plastic bag, a contemporary dilly bag, beckoning us to take stock.

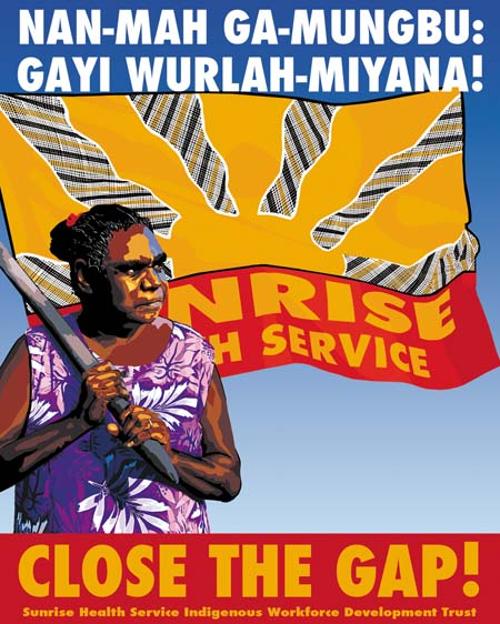

'Wallpaper' ran concurrently with 'Walls are Talking: Wallpaper, Art and Culture' at The Whitworth Art Gallery, University of Manchester. Touted as the first major exhibition in the UK of artists’ wallpapers, in which stereotypes of home improvement are subverted, it is interesting to note how the politics of place, race, and gender are common though half a world apart.