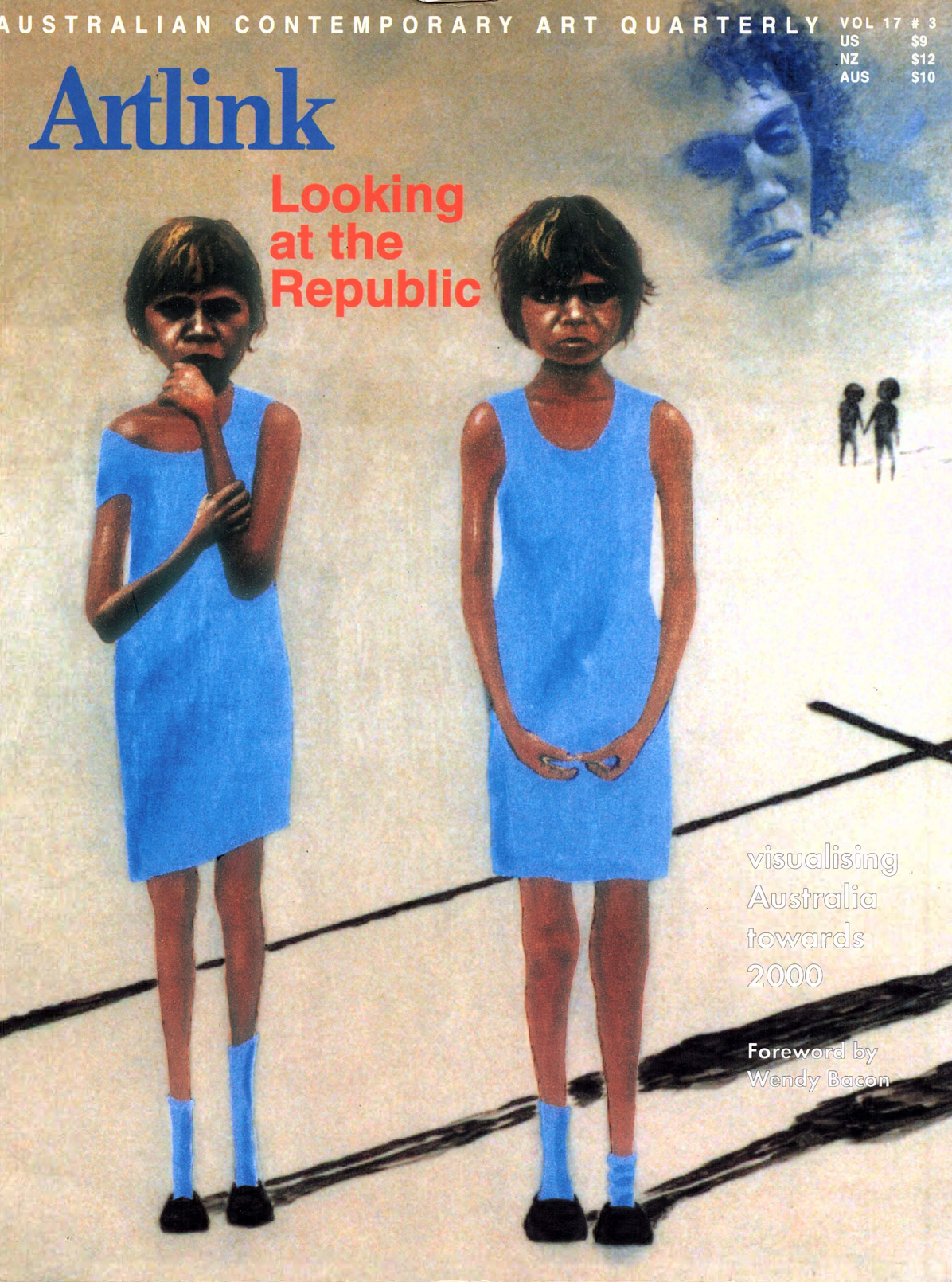

Looking at the Republic

Issue 17:3 | September 1997

Visualising Australia in the lead up to the new Millennium and a possible Republic. How will Australia re-present itself to the region? Icons and logos of Australia, a new flag, sport and porn, art for a banana republic.

In this issue

The Lie of the Land

Fiona Foley's 'The Lie of the Land' is an extraordinary piece of art and soundwork that illustrates yet another taking of land and culture from the indigenous people of this land.

A Postmodern Republic for a (West meets East) Post-colonial State

"Whatever the shape the Federal Republic pf Australia takes, there will be something unstructured, if not deconstructed about it. I imagine it as already impressionistic, figurative, eclectic, bebop. I'm only just game enough to say it might be the world's first post-modern republic, and I mean that in the nicest possible way."

The Sublime and the Parochial: The Foot of God

In Australia, the land has been, for non-Aboriginal settlers, from the beginning a sign for the nation and for the manufacture of livelihood (the sheep's back, mineral wealth) as well as a repository of dreams and misapprehensions. The importance of the land to Aboriginal Australian ought to be easy for us to comprehend.

That Iconic Moment: The Dismissal

1.30pm Remembrance Day. November 11, 1975 is a sacred memorial for the Australian Republican movement. This was the first time in Australian history that an unelected representative of the Queen had dismissed a Federal Government elected by the people.

Lines in the Sand

Craftspeople engaged with questions of nation and national and personal identity from their specific cultural backgrounds. Features the work of Arone Raymond Meeks.

Towards a Pre-Capitalist Flag

Australia's flag has as much to do with contests as with consensus. The original design resulted from a 1901-2 competition sponsored by a tobacco company.

Saluting the Dot-spangled Banner

Aboriginal culture, National identity and the Australian Republic. The closing ceremonies of the Atlanta Olympics were watched by a 1/5th of the world's population. This was arguably the most expensive bit of air time on the planet at that moment....

The Republican Rock: A Vexing Issue

Flags are vexing (vexillological) by nature. Explores the role of flags and the ways they have been subverted, with recent exhibitions recognising their irony and employing ideas that unpick the ideological rhetoric stitched into these symbols.

Three Fragments of an Aberrant Narrative of Australian Identity

Post colonialism provides a chimerical hope of a different means of shaping and ordering public representation of Australia, bu the institutional discourse around post-colonial arworks tends to uphold the status quo by using race/ethnicity as another means of directing scorn towards the lower reaches of Australian society.

The Stamp of Republicanism

When a nation puts out a stamp design it reveals a great deal about its official ideology. The designs which appear on stamps of countries which achieve independence and become republics follow a curious pattern. From France through Tsarist Russia to Libya.... what will Australia put on its Republican stamp [if and when it becomes a Republic]?

Thinking Like a Sheep, Acting Like a Ham

Some thoughts on performance and the Australian cinema. Verhoeven snuggles up to the sheep film as a clue to what Australian filmmakers have held dear. Nationalism and republicanism examined.

Glue and Yeast: Asian Perceptions and the Year 2000

The perception of 'culture' underlies all our relations in Asia. What are we? Are we as we are perceived? It is a really pertinent, dynamic interesting moment in our history, and in a wider world, in the history of this region.

The New Republics: Contemporary Art from Australia, Canada and South Africa

The ideas behind this project stem from the particular legacy of Black British arts practice in the 1980s....This touring visual arts exhibition and book project tries to deconstruct the notion of the centre (London/UK/Europe) both as a site of former colonial power and as a site of current economic and cultural power.

An Australian Head of State - Eureka!

Eureka - the First Australian Republic? was a touring exhibition which documented and interpreted the Eureka stockade. Containing paintings, drawings and prints ranging from the 1850s to 1994 as well as objects, documents and books related to or dealing with the Eureka Stockade the exhibition demonstrated the symbolic power this event has exerted on Australian political life as well as the imagination of artists.

Sport and Porn

Sport and Porn was huge in its scope and scale. The show ran for an hour and a half over a two week period at the Performance Space in Sydney during March 1997. Victoria Spence writes about the performance that she was involved in. The team comprised Morgan Lewis, Scott Wright, Sharon Kerr and Steve Howarth, Adam Kronenburg, Dana Diaz Tutaan, Victoria Spence and Rodgers D.

Art for a Banana Republic

Morrell contemplates the Banana Republic, a tourist destination with exotic indigenous culture and good weather. An Australian Republic seems to be inevitable...but where will art sit in this new future?

Festival of the Dreaming

Looks at the cultural events planned to accompany the Olympic Games to be held in Sydney in September 2000. There are 4 cultural festivals -- 1997 The Festival of the Dreaming curated by Rhoda Roberts, 1998 A Sea Change curated by Andrea Stretton, 1999 Reaching the World, 2000 Harbour of Life co-ordinated by Leo Schofield.

Symbols for Australia

Trademarks and logos have been vital ways of marketing goods and services for well over a century. What are the readily identifiable symbols for Australia?

Art as Cultural Diplomacy: Back to the Drawing Board

How would we re-present ourself to the rest of the world if we became a republic? It is the treatment of Australia's indigenous people that will ultimately determine both how we can imagine our own cultural development and how we are viewed by other cultures in the region.

The Path of Peace

Arts of Vanuatu

Ed Bonnemaison, Huffman Kaufmann, Tryon.

Published by Crawford House

RRP $69.95

Travelling North or Going Backwards?

Is Australia an Asian Country? by Stephen FitzGerald

Allen and Unwin 1997 RRP $19.95.

Cheating Tragedy

The Art of Gordon Bennett

by Ian McLean and Gordon Bennett

Craftsman House

RRP $75

Hard Edge Political

Lawyers, Guns and Money

19 June - 7 September

Experimental Art Foundation

Lion Arts Centre, North Terrace, Adelaide.

A few more fish than you'd expect for seven bucks

Still Life: Still Lives

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

6 June - 27 July 1997

Post-Colonial Dreaming

Mapping the Comfort Zone: The Dream and the Real

works by Irene Briant, Jenny Clapson, Jo Crawford, Christine James. Catherine K, Nien Schwartz, Lucinda Clutterbuck & Sarah Watt.

Artspace, Adelaide Festival Centre

4 July - 16 August 1997

Disclosing Secrets

Terr(or) Firma Terr Affirma

Brenda Goggs Prospect Gallery South Australia

1- 22 June 1997

Mothertongue

Re Affiliations

12 June - 13 July 1997

Margaret Sanders, Claudia Lünig, Clare Martin, Hanh Ngo, Maria Stukoff, Lisa Jeong, Paloma Ramos, Madelaine Neveu

Nexus Gallery, Adelaide

To Have or to Hold

Containment

Debra Dawes, Zsolt Faludi, Gwyn Hanssen Pigott, Carlier Makigawa, Susan Norrie, Mary Scott. Curator: Clare Bond.

Plimsoll Gallery, Hobart

12 April -2 May, 1997

University Gallery. Launceston

2 - 31 July, 1997

Reviewed by Mary Knights

Ngarrindjeri Soldier Kerry Giles Kurwingie 1959 - 1997

Artrave

vis.arts.online

Different Dreaming

Lap : an installation view Keitha Phelps

Five Different Homes: Louise Haselton

Contemporary Art Centre

19 November- 12 December 1993.