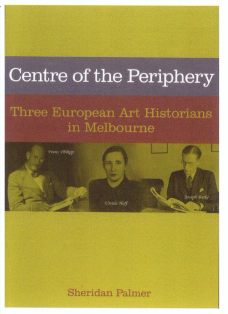

How art history arrived in Australia, and inevitably found itself centred in Melbourne, is an unusually interesting study. Only in Melbourne was there a tycoon trustee of a state art museum - newspaperman Sir Keith Murdoch, president from 1939 of the State Library, Museum and Gallery – also exceptionally gifted at art world politics. He plotted to professionalise the very wealthy National Gallery of Victoria, in 1941 installing a fresh director, Daryl Lindsay, who soon hired our first art history graduate curator, Ursula Hoff, a specialist in Rembrandt. Murdoch then endowed the University of Melbourne with Australia's first Chair of 'Fine Arts’, an art history department where a course began in 1948. Professor Joseph Burke was expected to use the NGV’s staff and collections for his teaching, and to give half his time to enlightening the public outside the university.

Burke was an early product of London’s first art-history courses at the Courtauld Institute, intellectually enriched by Jewish art historians exiled from Hitler’s Germany. Specialisation in 18th-century English art, an interest in contemporary industrial design as well as contemporary art, and above all charismatic public speaking and a clubbable way with men of money, made the well-connected Englishman perfect for Melbourne.

Hoff arrived in 1939 when the Principal of Melbourne University Women’s College asked her counterpart at Cambridge if she could recommend a graduate Jewish refugee to be College Secretary. Daryl Lindsay invited Hoff to launch a series of lunchtime lectures at the NGV and in 1943 poached her away from college administration; they made an excellent team, she more adventurous artistically than him and, above all, free of Australia’s excessively British tastes.

Professor Burke also hired Hoff – part-time, usually evenings, outside NGV working hours – for his new Fine Arts department. Much of the course-work was devised by Franz Philipp. Shipped from England on the notorious voyage of the Dunera in 1940, to internment in the Australian bush, Philipp enrolled at the University of Melbourne, graduated in history and became a tutor, but then transferred to Burke’s department.

Hoff and Philipp were respectful colleagues (she had first spoken to him through barbed wire at Tatura, visiting the inland internment camp with an International Refugee Committee) and they both came to despise Burke, unjustly. Hoff was a product of Erwin Panofsky’s art history school at Hamburg, where his ‘Iconology’ had shifted art history away from ‘simple connoisseurship’. Philipp was a product of Vienna, where they rejected ‘the material language of artefacts [and] belletristic nonsense’ to study ‘works of art as mirrors of the culture in which they were produced ... of social, religious and philosophical ideas’. Hoff and Philipp both engaged fruitfully with the local avant garde art scene, as had been usual in their German milieux.

When students fretfully inquired whether the work they studied was good art, Hoff reassuringly confirmed that whatever she presented was, she hoped, outstandingly excellent, and insisted that art had to have ‘significant form as well as significant content’. Burke on the other hand accepted one of the beliefs of his mentors ‘that you take the bad pictures as well as the good to read as documents of the age under study’ and cheerfully conceded he liked them all.

The book concludes in 1956, the year when Hoff acquired an extraordinary collection of masterpiece Renaissance prints by Dürer for the NGV; and when the Melbourne Olympics made the city feel at last fully internationalised, no longer extremely peripheral.

Australian Scholarly Publishing specialises in converting university research into books. Production is excellent, with good illustrations and design. The copy editor is thanked, no doubt for the rather stiff style, nervously on guard against grammatical ambiguities. Names on the other hand are an immense mess: the ‘British Arts Council’ could be either the Arts Council of Great Britain or the very different British Council; Sydney Cockerell appears as ‘Sidney Cockerall’, Renaissance scholar Burckhardt as ‘Burchardt’; the modern European artist Moïse Kisling becomes ‘Moshe Kisler’; we encounter European masters ‘Gaugin’ and ‘Lorrain’, the musician ‘Hepzibeth’ Menuhin, the Australian art historians ‘Joseline’ Gray and Rosalind ‘Hollingrake’, the sculptor ‘Yomantis’ – and many more. That’s sloppy editing, not scholarly publishing.