Taken together, the three exhibitions presented by the IMA for the summer holiday season are a surprisingly significant historical document of contemporary art in Brisbane. They provide a revealing view of what's changed during the past three decades, and what's remained the same.

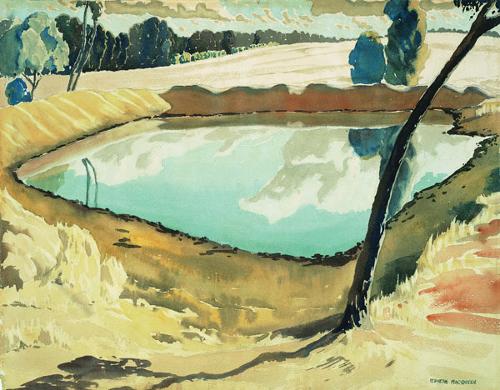

What hasn't changed is Robert MacPherson's central presence in progressive art in this city. The official opening of the IMA in 1975 was marked by an exhibition of his work. His most recent showing combines themes that have remained constant in his work for many years: the private language of subcultures (including art history) and the parallels between daily life and art-making. The exhibition comprises two installations. The bigger of the two, 'Popov And The Lost Constructivists' (1982-2007), is a large collection of pseudo-constructivist assemblages made from odds and ends. Many Russian migrants settled in Brisbane during the first half of the 20th century, and MacPherson's installation raises the possibility that some of them might have been linked to the constructivist movement in Russian art. Relocating to Brisbane eliminated the possibility of participating in that momentous cultural event, so MacPherson has produced the never-realised works of art that might have been made by émigré Russians in Brisbane back sheds and workshops. A collection of newspaper death notices, originally of Russian migrants, but expanded to include anyone with a nickname hangs in long strips on one wall.

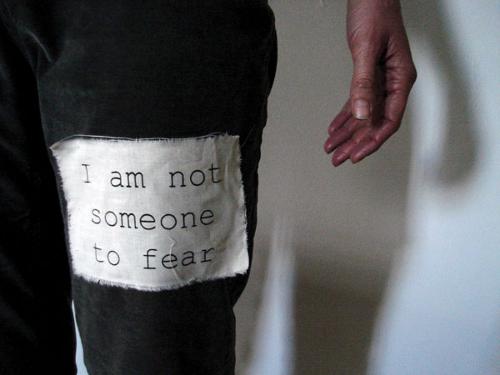

The exhibition by Vernon Ah Kee, a prominent but much younger Brisbane artist, would have been unimaginable 30 years ago when the IMA opened. In those days Indigenous artists, for many reasons, were not participating at the forefront of contemporary international art the way MacPherson was. Ah Kee is best known for text pieces that are stingingly precise in their content and presentation. He combines these with six surfboards painted with traditional North Queensland rainforest shield designs for his IMA installation 'Cantchant'. The installation deals with the Australian surfing culture, and the way it became the focus of racist aggression at Cronulla in 2005. Anglo-Aussies taunted Middle Eastern immigrants with the chant 'We grew here, you flew here', a claim to native status that sounded a little hollow to Indigenous Australians. Ah Kee's installation was strangely reminiscent of an anthropological museum display, dominated by fine tribal artefacts explained by wall texts. Everything, however, was incongruously skewed. The artefacts were a complete invention, and the writing on the wall undermined simple straightforward explanations instead of providing them. The surfing motto 'hang ten', in big letters, took on a new and disturbing meaning in the context of Aboriginal history. In a surfing video on three screens three black surfers in comically trendy beach clothes and shades make their way down to the water, acting deadly cool and creating a picture that the viewer becomes acutely aware of having never seen in reality.

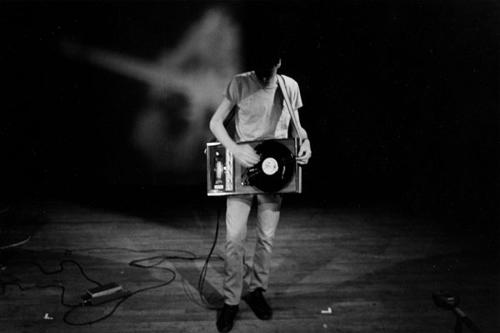

A compilation of video recorded performances from 1991-1995 by the late Jeremy Hynes was a reminder that for a brief, exciting period Brisbane was a hotbed of exceptionally good performance work, often presented at the IMA and dominated by Hynes. He had long since moved on from that phase of his career, but in 2007 when he was killed crossing the street, the shock and grief that spread through the local art community was partly caused by the recognition that Hynes represented a remarkable cultural moment that was over. The compilation by Ben Wickes, a friend and sometime collaborator, is tightly edited and moves at a rapid pace, appropriate to the abruptness and latent violence that often distinguished the performances. Hynes created unforgettable images: a man (him) clawing a hole in a mattress and crawling in; swimming through a huge clear plastic tube of water and cutting his way out, to be washed down the street by the released torrent; swinging a mallet onto explosive charges; setting fire to things (such as his clothes). Like MacPherson, Hynes could make art out of nothing. He was an artist of frenetic energy and inventiveness, with a capacity to think and work at disconcerting speed. Apart from anything else, the videos record an era when the IMA was housed in places where artists could perform dramatically destructive acts. These days you don't throw sheets of mirror glass down the stairs of the IMA or drop cinder blocks from the ceiling to the floor. It isn't that sort of place anymore, and people are no longer making that sort of art.