Ventriloquism: On the commodification of masculinity in South African art

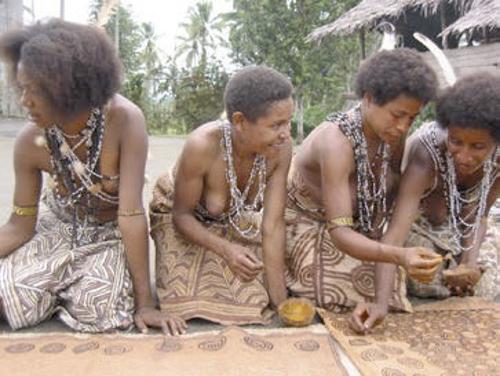

On the cover of a glossy magazine geared for the off-road vehicle enthusiast is a picture of Xhosa male initiates set in an idyllic landscape. The initiates are wearing nothing but the characteristic white body paint and blankets, and they carry sticks. This kind of image can also be seen in a number of different consumer products including postcards and tourist brochures.