Czarnecki, Robbie Page, Helly Hanssen and NTL.

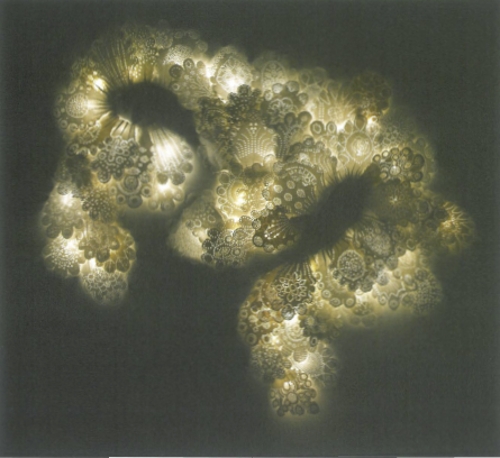

There is nothing quite as acrid as the smell of burning rubber and it's always easy to know if you are in the vicinity of a 'burn out' by the pungent aroma of wheels on fire. If there was one thing missing in Mike Stubbs' recent exhibition at the Experimental Art Foundation it was this smell – so instantly recognisable and associated with hotrods and hooligans.

In Burnt, Stubbs presented a series of video works that document and comment upon various aspects of contemporary British culture. With a particular focus on the north of England, Stubbs (originally from England and now based in Australia) presents a culture in crisis, fuelled by a lust for war and oil and grasping at strategies to rebuild a cultural identity.

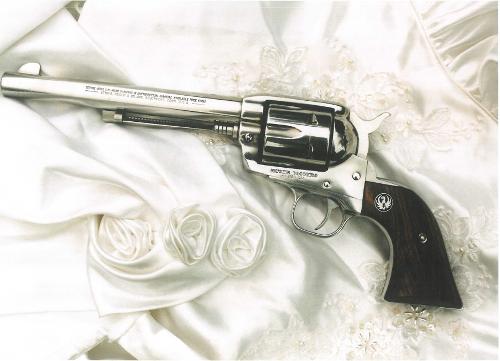

The two-screen work Donut shows, in opposing projections, lads in the act of making donuts or 'wheelies'. This is not just a random burn out captured on video, it is in fact a performance staged and directed by the artist. Perhaps reminiscent of his own misspent teenage days, Stubbs is both participant and performer in this homage to car culture and piston-fuelled male bravado.

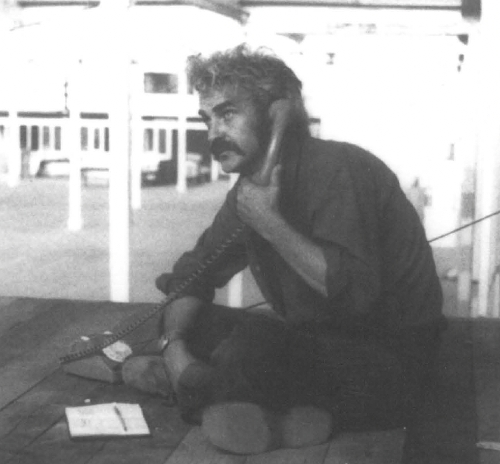

Stubbs is also performer in the single screen work Jump Jet. Facing the camera and donning a fighter pilot helmet, he offers up a series of sound bytes such as 'we need a good war' or 'a good reason to live in the Balkans – petrol is cheap there'. Interspersed with images of a Royal Air Force Harrier jump-jet, Stubbs adopts a military persona to present pervading views across Britain – that petrol is too expensive, that politics is obsessed with the price of oil. With Jump Jet placed in close proximity to Donut, the two have a strong relationship with each other and highlight a testosterone driven machine culture. Stubbs effectively draws a parallel between cultures of consumption and aggression.

As much as Stubbs is fascinated with presenting this culture and somehow being immersed within it, he also shows the fragility and vulnerability beneath the macho façade. Lurking in the back corner of the EAF gallery is another video monitor. Encased in a fabricated mount and positioned at ground level, this work entitled Tyne, is a video of a young man sitting on the edge of a bridge that crosses the river Tyne in Newcastle. It is a pathetic scenario where a distressed young man becomes just another vehicle for entertainment, with a gathering crowd egging him on to jump.

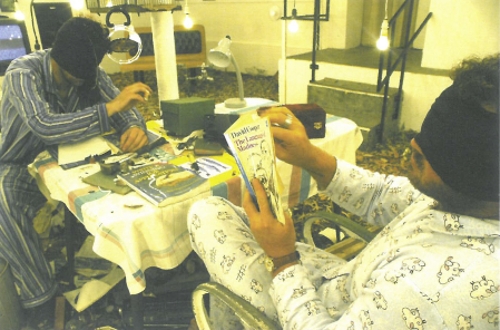

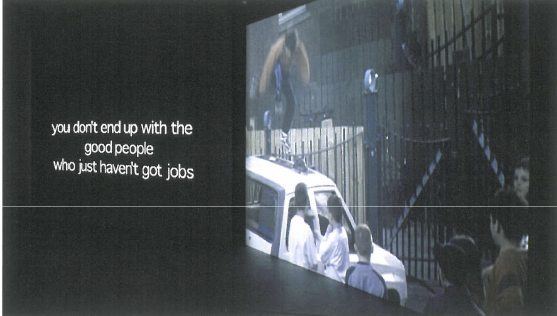

The work Tyne is an indication of Stubbs' interest in looking at the cracks in the system, at exploring a cynicism and malaise that dominates post-industrial societies in transition. This is very much at the fore in the work Cultural Quarter where we witness a group of young kids (ranging from around 5 – 15) taking apart, stripping and torching a car in the middle of a group of council flats. Watched on by parents, this is obviously a form of recreation and amusement where the kids are encouraged to smash and plunder the stolen (or abandoned) vehicle.

The bizarre scenario played out in Cultural Quarter is made more poignant through its placement next to a video showing Newcastle awaiting the outcome of their bid to be 2008 European Cultural Capital. Winning the bid appears to be essential for a bright future in Newcastle – this will put the struggling city on the map and engender a new sense of 21st century civic pride. But as we see kids setting alight the abandoned car on the adjacent screen we also see the hopes of Newcastle civic pride sink as Liverpool is announced as the successful host.

Burnt is a somewhat personalised lament for an England that is in decline. Yet there is also a celebration inherent in the video works and their relationship to each other – there is a strong sense of anti-authoritarianism and an 'up you' attitude. This is anarchy in the UK where the streets are reclaimed for the citizen and become a contested zone for marking ownership, identity and visibility.

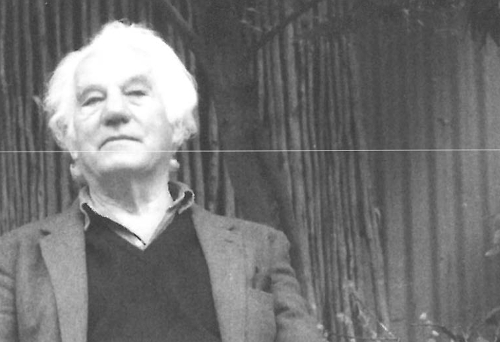

Throughout the suite of works in Burnt there is a strong sense of the artist himself – he is not just an observer or documenter of what is going around him, the artist is in fact an active participant, who is just as much a product of the culture as the individuals contained in his videos.

And as the artist successfully invokes burning rubber as the signature smell for Burnt - perhaps the accompanying soundtrack would be the 1977 Sex Pistols' anarchic anthem God Save the Queen:

When there's no future how can there be sin

We're the flowers in the dustbin

We're the poison in your human machine

We're the future your futureGod save the queen we mean it man

There is no future in England's dreaming