People involved in the arts and education might have difficulty recognising the Australia that the Treasurer has been talking up recently: the one with the record 4% low unemployment. But the Treasurer's spin fails to mention that to be counted as employed you only have to work one hour per week, which bears out the reality of a life in the arts.

While tenured academics have for some years had every last drop of life squeezed out of them, part-timers are in these days of individual workplace agreements treated so badly that their jobs are hardly worth having. The drain of talent is leaving teaching institutions impoverished. There are art school studios with not enough practitioners to pass on the traditions of visual communication and theory departments desperately seeking projects with 'industry' to rake up those all-important research points to fund their teaching.

An arts administration graduate doing what is really work experience is counted as 'employed'. Whole communities whether in country towns, regions, or outer suburbs have virtually no exposure to good contemporary arts, leaving small core groups of local artists to make the running. Regional galleries have to manage without paid staff. High school students are often steered away from the pointy end of contemporary art by conservative and ill-educated teachers, whose own training may have lacked significant contact with current practice. This phenomenon is also reported, incredibly, at art schools where students don't go to exhibitions unless they are made to.

The art market continues to pump out its mumbo-jumbo; in the immortal words of Murray Whelan, hapless advisor to the new Arts Minister in Shane Maloney's 1996 novel The Brush-Off, 'In comparison with art criticism, the mealy jargon of bureaucracy sparkled like birdsong. Not even in the mouth of the Leader of the Opposition did words convey so little.'

The obscene gap between the amount of resources available to the humanities and sciences and those absorbed one way or another by industry and consumer culture is both a symptom and cause of intellectual decline. (And Sol Trujillo's salary at Telstra, at only a measly $8.7m p.a. plus a bonus of $2.6m, is round about three times less than he was getting in the USA.) But when the crunch comes, and the oil has run out and Australia has to deal with is own ecological and economic crisis, where will the thinkers and creative minds be who can cut through the unreal world of global corporate excess?

Still sitting on the scrapheap waiting to be called? The petitions keep coming on the email to stop the relentless progress of governments to dismantle our civil society. One day it's offshore detention for asylum seekers. The next it's the grab-back of Indigenous Land Rights. Then the slaughter in the Middle East. A massive woodchip company can sue 200 citizens who dared to stand up to its despoiling of irreplaceable old growth forests – without a peep from the state government.

And if artists fiddle while Tasmania burns they might be doing the only sensible thing – if they can afford the fiddle.

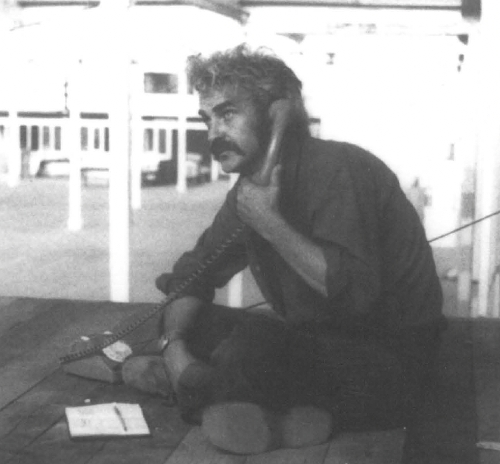

December sees Artlink tackle an issue that will affect us all – ageing. Elders: artists, curators and writers in their late seventies and eighties who are still practising, are being interviewed about what they thought art was 40-50 years ago – and if its current incarnation is just a meme or two away. At 25 years old Artlink itself is getting to be an art magazine senior. But if eighty is the new forty, what does that make 25?