Colliding Worlds is a well-researched, thoughtful and brilliantly curated exhibition that ought to be mandatory viewing for all Australians, regardless of background. It offers extensive visual documentation of the first encounters between Western Desert people and non-Indigenous people, the most recent of which, remarkably, only took place in 1984.

The exhibition, developed jointly by Tandanya and Melbourne Museum, comprises, inter alia, archival photographs, many of which are high quality, including photographic portraits of Indigenous adults and young children taken for research purposes, either 'scientific' and/or anthropological in focus. One really nice touch in this exhibition is the inclusion of more recent 'adult' photographs of the same young children, some of whom have since become celebrated artists. For example, a photograph of a naked, cheekily smiling nine-year old Mick Namarari taken in 1932 contrasts with a photo of more sombre-faced Namarari, taken some 60 years later, against the background of one of his own acrylic painting.

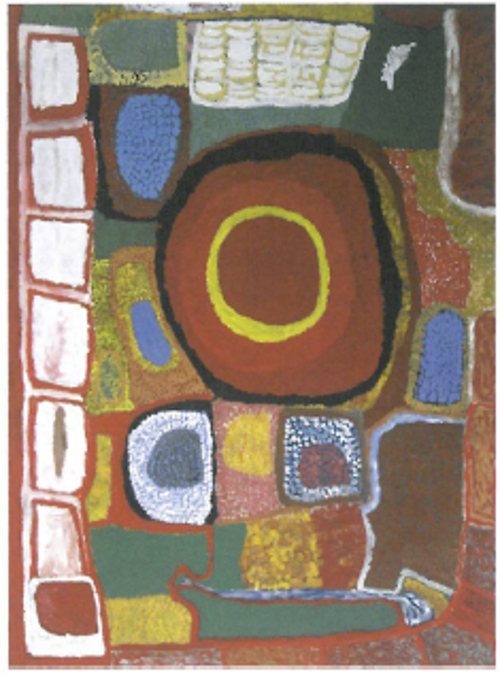

Stills taken from film footage of these inaugural meetings between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people are also included in this exhibition. Paintings of country – including a number of magisterial works by prominent Western Desert artists of the ilk of Uta Uta Tjangala – along with some earlier, more diagrammatic sketches by Pintupi artists also play a significant part in Colliding Worlds. Facsimile reproductions of relevant newspapers and booklets also document these first, unrepeatable, life-changing meetings. A display cabinet contains examples of Indigenous clothing, including a pubic hairstring tassel, and ceremonial woven hairstring belonging to a woman called Waripanda. A wooden collecting bowl, presumably belonging to the same woman, is also in this cabinet.

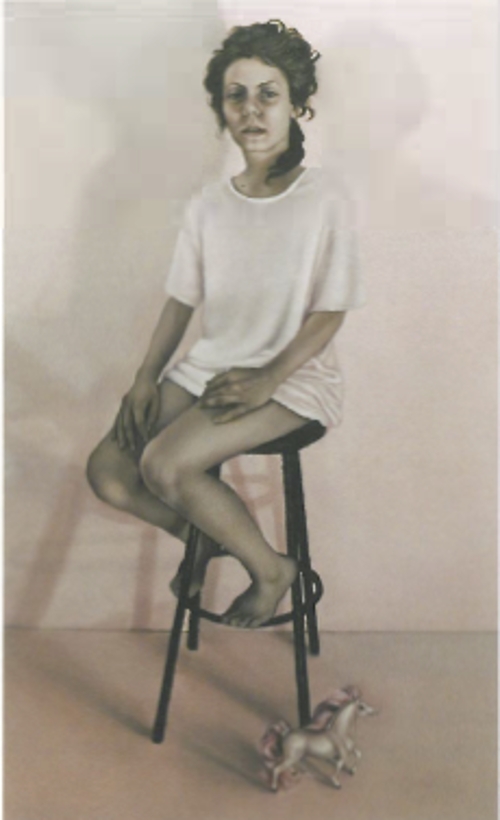

There is even a plaster 'life-cast' exhibit of Waripanda's head and upper body, which, while not quite as shocking as it may sound, because she has been contextualised and humanised by the personal belongings and accoutrements that surround her, and also because, importantly, Waripanda has been named, do make us feel slightly uncomfortable. The approach certainly contrasts with that of many anthropological displays of earlier colonial days, when Indigenous people were often flaunted as nameless exhibits, their anonymity divesting them of the truly human status contingent on acknowledging individual identity. Here by contrast, Waripanda's dignified bearing is that of a woman in her prime who has considerable self-respect. Nonetheless, there is something about Waripanda's self-possessed look, her steady, unflinching gaze (albeit partially a product of being immobilised by the plaster cast in which she was encased), her way of staring back at us – perhaps somewhat accusingly - across the intervening years, that is distinctly unsettling.

In addition, a luminous satellite photograph of the Lake Mackay ('Ngayurru' in the Warlpiri language) area in the far west of Central Australia, spilling over the border into Pintupi country and what is now called the Western Desert, is juxtaposed next to a vibrant, contemporary acrylic work, Tjampirrkungku (1996) by a Western Desert woman artist, Katarra Nampitjinpa. The twinning of these images has produced a remarkable composite image of this vast region.

My only (minor) point of contention as far as this marvellous exhibition is concerned relates to the first part of its title. Certainly at one level, epistemologically, and in terms of inequality of power relationships, these were and still are, in many cases, unquestionably 'colliding' worlds. But while, in some cases, the implied violent conflict was to come very soon after this, and the parties were to enter into the seemingly permanent collision course that typifies many colonial encounters, these very first meetings, from the visual evidence presented, seem to be have been underpinned by mutual fascination and hope on the part of the Indigenous and non-Indigenous people involved. In the photograph of a Pintupi man, Pitani Tjampitjinpa, examining an apparently pristine (apart from the red bulldust partly covering it) truck emblazoned with words announcing Donald Thomson's BINDIBU (Pintupi) EXPEDITION.

Tjampitjinpa's hand is placed on the truck in such a way as to suggest considerable interest in what the interlopers might have on offer, rather than 'collision', or even the potential for violence. Of course, just how posed these compositions were we will probably never know with certainty.

As far as the majority of the visual evidence presented in Colliding Worlds is concerned and despite the fact that in terms of the archival photography at least, the visual data is one-sided, considering the hands that held the cameras and literally 'called the shots' – visually, these first encounters, for the most part, do not seem to augur the violence, the dashed hopes, disillusion and despair that often followed.