The famous 1939 Herald Exhibition of French and British Contemporary Art, which consisted of 217 works, first opened in Australia on 21 August at the National Gallery of South Australia and ran for almost a month. It was sponsored by Sir Keith Murdoch and promoted by the Herald and Weekly Times newspapers, including the Adelaide Advertiser.

The exhibition generated enormous public interest, with an attendance of over 7,000 people, including school groups, and enthusiastic responses from local artists such as Hans Heysen and John Goodchild. Yet typically, art books refer to the Adelaide showing as a minor dress rehearsal for much more significant showings in Melbourne and Sydney. This myth is one of many concerning the exhibition, which are unravelled by Eileen Chanin and Steven Miller in their splendidly researched and lavishly illustrated book.

Mythology regarding the Herald Exhibition has arisen for various reasons; from struggles between proponents of academic art and modern art, between Sydney and Melbourne in competition for leadership in modern art, from arguments about whether the exhibition was the first modern art exhibition shown in Australia, from conflicting opinions as to how contemporary the works actually were and from disputes about the exhibition's influence on Australian art history, to list only some.

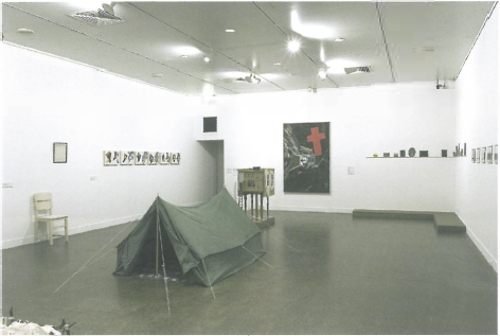

Regarding opportunities for art historical influence, it has long been believed that the exhibition was on view for only a few months in 1939 and then stored in state art gallery basements for the duration of the war, due to backward-looking trustees and their hatred of modern art. Chanin and Miller document the exhibition itinerary, proving that selections from it were re-shown throughout the war and in five Australian states, thus giving many people the opportunity to experience the works. On broader questions of the nature and quality of the works and their potential to inspire and influence local artists, we can now make judgments ourselves. Few works have previously been identified but the authors have located many and illustrate approximately one hundred in the order in which they were listed in the original catalogue.

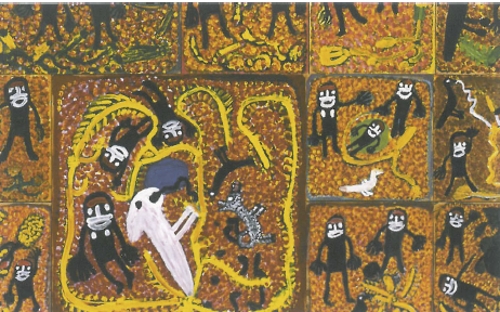

On viewing illustrations of some of the remarkable artworks in the exhibition it seems strange that its impact was ever in doubt. There were major paintings by great artists such as Cézanne, Van Gogh, Gauguin, Matisse and Picasso. One third of the works were contemporary, that is of the 1930s and novel to Australian artists. They were chosen by the exhibition's curator Basil Burdett to illustrate a linear history of modern art. Though this did not include all modernist styles it did illustrate a progression, indicating that the next big thing would be surrealism. It is no accident that during the war years Australian modern art exhibitions, such as those of the Contemporary Art Society, featured a range of 'isms', including many works inspired by surrealism.

Many works in the Herald Exhibition were for sale and, because of the difficulty of expatriating them during the war, available at negotiable prices. Unfortunately, few were purchased by state galleries and Australia missed a unique opportunity to acquire key works of modern art. Miller and Chanin explore the paradox of Australian art politics between the wars that led to this situation. While some artists, collectors and educators were open to modernism, and the public accepted it in design and advertising, some trustees and directors of state art galleries saw it as a threat. At least one fulminated in Hitlerian terms. J S MacDonald at the National Gallery of Victoria criticised artists represented in the exhibition as degenerates and perverts, echoing Hitler's simplistic racial and artistic theories and infamous exhibitions of 'degenerate' art. If an artist used distortion in representing forms, for example, he obviously did not have the power to perceive correctly, being racially degenerate.

The book's title reflects the 'take no prisoners' attitude of art criticism of the time. Miller and Chanin remark that J S MacDonald committed professional suicide by his remarks on the exhibition. Nevertheless he went on to make more trouble as a witness in the Archibald Prize lawsuit of 1943 concerning a portrait of Joshua Smith by William Dobell.

Chanin and Miller's book is a fascinating account of Australian art and culture between the wars and the Herald Exhibition of 1939 which completed the period. They argue that the exhibition was not a watershed that changed the course of Australian art, but part of a running tide of change. As to the question of influences on individual artists, that is largely left to the reader with plenty of evidence provided for pleasurable speculation. However, influences may not be directly visual. John Goodchild is quoted as saying that the exhibition would challenge Australian artists. The bar had been lifted. Imagination took precedence over gum trees.