Tightly assembled in Heide's compact galleries, Good Vibrations: The Legacy of Op Art in Australia packed a considerable intellectual and visual punch. Other institutions may be larger, better funded and more widely publicised, but with projects like this one Heide strides to the forefront of intelligent interpretation. The exhibition spaces were alive with a certain buzz; colour and patterns covered the normally white walls, the public were enjoying themselves and there was hardly a representational image in sight. Good Vibrations won on all accounts. It was ingratiating, entertaining and approachable but it was also a cogent and informed outline of a period of Australian art and its influence on subsequent generations of artists, reminding us that contemporary art has been thoroughly institutionalised for half a century. It was a show with a clear thesis, but in a relatively rare exception to the norm the curatorial gesture was enlightening, unobtrusive, non-histrionic, drawing attention to the works rather than the gallery staff. The chosen exhibits all had an effective gallery presence. The compilation of works and the catalogue essays only served to enhance and inform the visitors' experience and both texts and exhibits expanded the known story of Australian art and understandings of art in the 1960s.

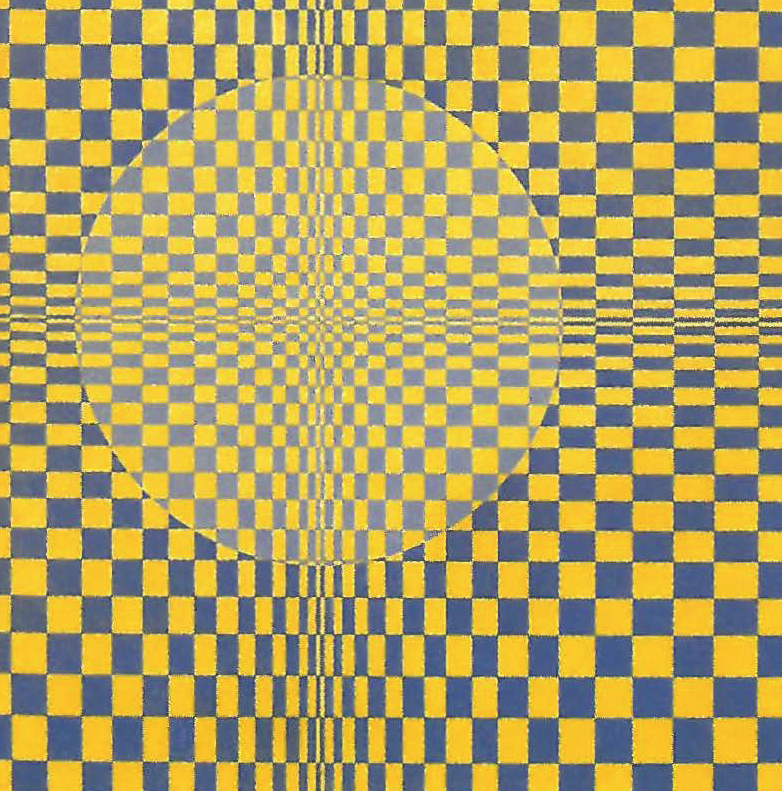

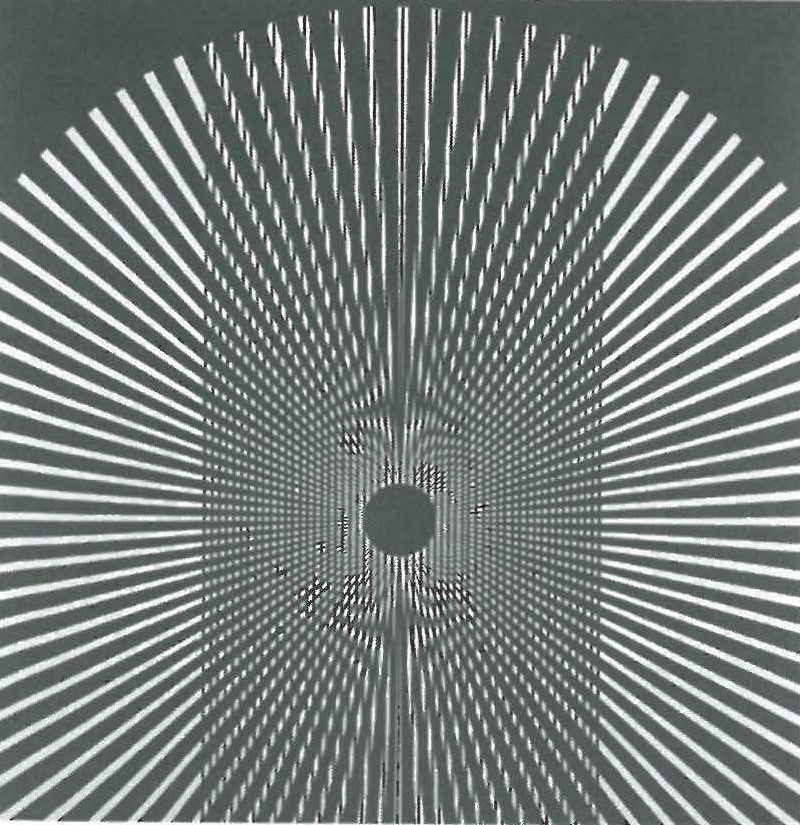

Remarkably, given the frequent history of tight budgets and missed opportunities in Australian collecting of international contemporary art, Good Vibrations could credibly fill in the overseas sources of contemporary art, drawing only from Australian collections. As many of these works have not been seen in public for decades, it was exciting to see such works as Jesus Raphael de Soto's Ecriture de Londres 1965, purchased in 1966 by the National Gallery of Victoria's Felton Bequest. Though a little grubby on the white surfaces, suggesting long years in storage, its kinetic wires hung against painted lines still provided a visual impression of dissolving hard lines and remains compelling when brought out on show again. Likewise the Felton Bequest also provided an impressive Vasarely and a Bridget Riley oil in the next year, 1967. Riley has particularly captured Australian attention with a range of paintings acquired by both institutions and private buyers over three decades. The classic and Eurocentric tendencies of the prints and drawings collection of the NGV, with its centralist interpretation of the 'contemporary' here were not predictable and tame but were thoroughly justified. The Power Institute and the private collections of Anne Lewis and Kerry Stokes were also evident.

Not only did Good Vibrations provide an informed overview of European and American art of the period, it revived a few Australian reputations. Stanislaus Ostoja-Kotkowski was revealed as a leading figure in the local exploration of Op Art values, with a number of brightly strobing works in various media poised between his early textile and stage designs and his pioneering electronic works. Early examples of kinetic art included a Frank Hinder and expatriate John Vickery, resident in the United States since 1936, provided impressive abstracts. David Aspden, Dale Hickey and Gunter Christmann, as young artists, also were responsible for some effective mid-1960s Australian responses to the Op Art phenomenon. Lesley Dumbrell emerged as an artist who, like Riley, has pursued a single-minded and effective exploration of visual phenomena in abstraction.

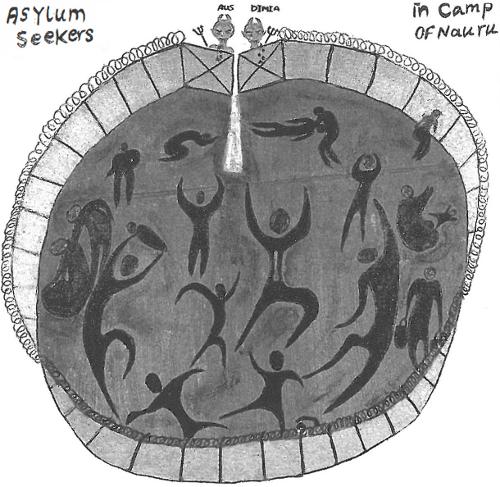

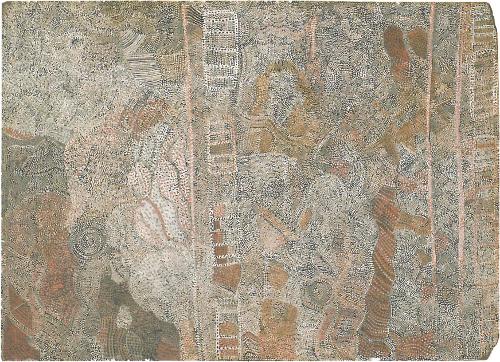

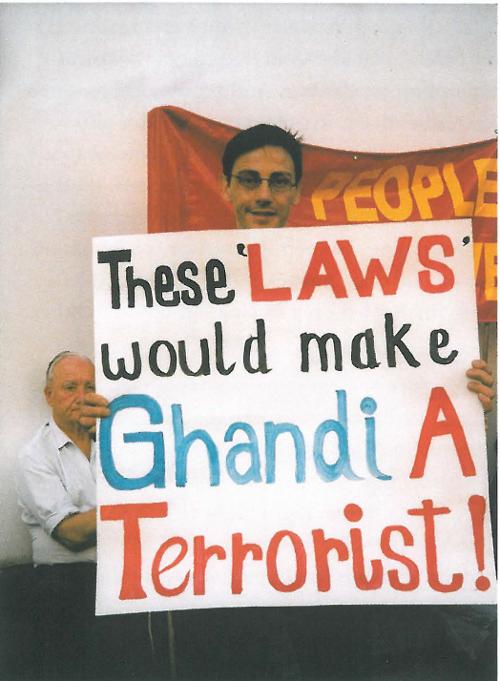

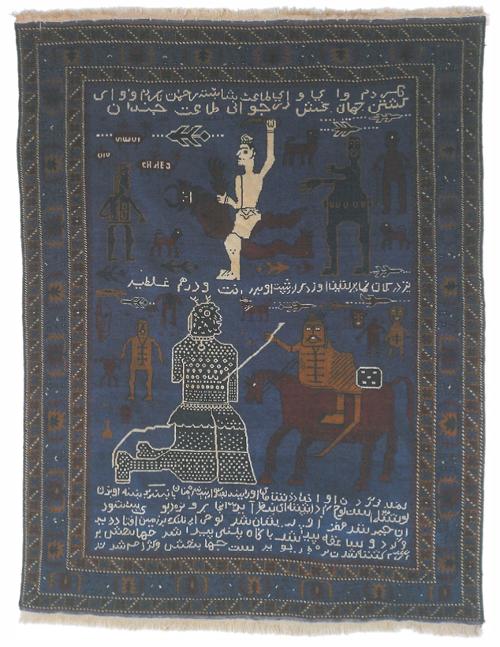

In tracing the influence of the movement, Zara Stanhope's definition of Op Art was more loose and inclusive than purist, embracing pop art elements with Edouard Paolozzi prints and early kinetic and video works. This flexibility allowed for an effective exploration of the many meanings that the style holds in present day Australia including installations and post-colonial pieces for example John Neeson's beautiful Bridge of Sighs in which the shifting patterns moved as the viewer walked past. Louise Forthun's Bridget indicates that artists are aware of the sources of this current interest in visual pattern and optical effects.

Op art has become extremely popular due to such phenomena as the Austin Powers films that have brought the patterns and colours of the mid 1960s back to life in ever more exaggerated formats. Digital imaging, computer graphics and the popular experiments with fractals have allowed for a more precise and easier exploration of patterns. Discount fashion chains sell Riley-esque patterns in printed nylon. As Sandra Kaji-O'Grady indicates, the very popularity of Op art made it highly suspect in the dominant tradition of North American formalism in the mid 1960s, but the fading of Greenbergian purism with time and the growing acknowledgement of the popular in contemporary art gave Good Vibrations a happy and appreciative generalist audience and also has fuelled the current revisiting of the movement amongst living artists.