The 2002 Adelaide Biennial of Australian art offered the opportunity to explore the complexity of political, sociological and cultural debates of our futures. This kind of collaboration between art and science can offer a space to consider the tensions between interrogation and contemplation, comfort and discomfort. From this perspective, much of the work within conVerge: where art and science meet allowed speculation on not only past and future worlds, but specifically of human habitation within them.

Oron Catts' and Ionat Zurr's bio-medical installation of a fully equipped xenotransplantation laboratory occupied the space as a microcosm of genetic engineering. Tiny pairs of wings were grown for the duration of the exhibition from living pig tissue, and as such, Pig Wings traced a speculative path from fear, to idea and back again.

In this context, Patricia Piccinini's animatronic Synthetic Organism 2 (SO2): The Siren Mole seemed positively benign. The public fears of the possibility of pig-part transplantation seemed absent in this work, replaced instead by an aestheticised and arguably romanticised view of bio-medical futures.

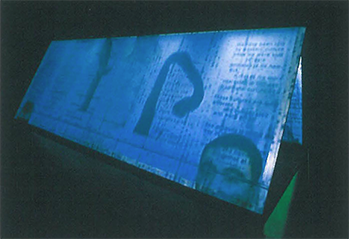

Justine Cooper's large-scale projection/installation Transformers, presented the overlapping datum of identity – fingerprints, DNA codes, personal narrative, translated memory – offering a hypnotic meditation of the constitution of individuality in an environment of increasingly universal medical mapping.

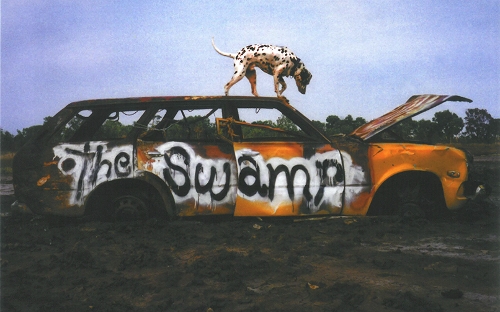

For Martin Walch, contemporary landscape exists as the domain of human intervention, with both seductive and repulsive results. His tiny stereoscopic viewfinders offered views of expansive, achingly beautiful other-worldly landscapes – in terrifying reality, the environmental destruction of the open-cut mines of Tasmania's Mount Lyell.

Human traces were perhaps no more clearly or seductively invoked than through Adam Donovan's Perimetry. As an immersive and interactive installation, Perimetry invited the viewer to engage in spatial definition through the robotic tracing of the viewer's movement through space. The subtle sounds created by the slightest movement made for a truly self-conscious experience. (I felt equally self-conscious watching the seemingly endless loop of Jon McCormack's Universal Zoologies. I couldn't help but feel for McCormack's anamorphic running man; the sheer awkwardness and the exhaustive weight of synthetic gravity made me feel glad to be human).

The glamour and wizardry of high-technology – not to mention its unreliability to function as intended – arguably risked compromising much of the Biennial's critical objectives through its mesmerising distraction. While attempting to cross the boundaries of traditional art museum engagement – touching, poking, prodding was intrinsic to many works – engagement seemed dependent upon first negotiating viewers' trepidation of interacting with the technology itself, and their subsequent disappointment if nothing happened.

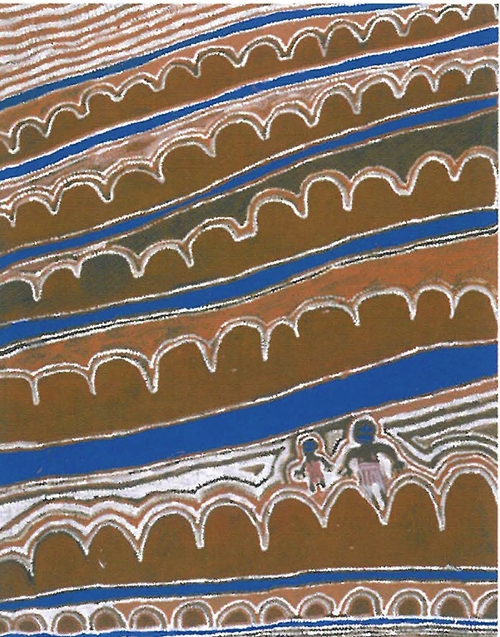

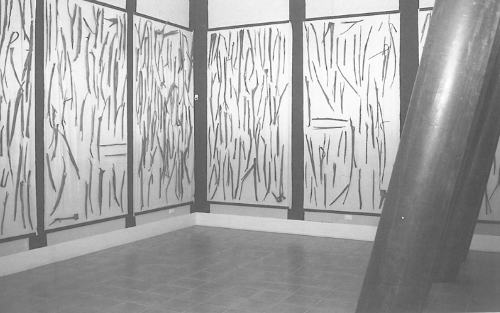

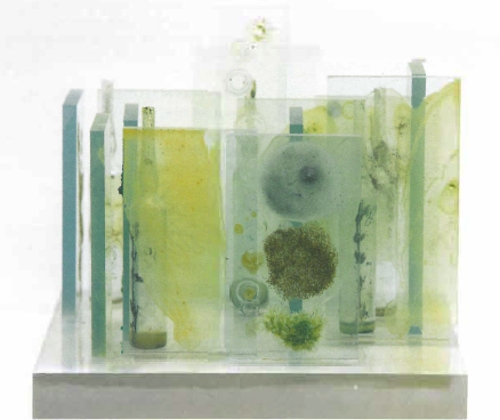

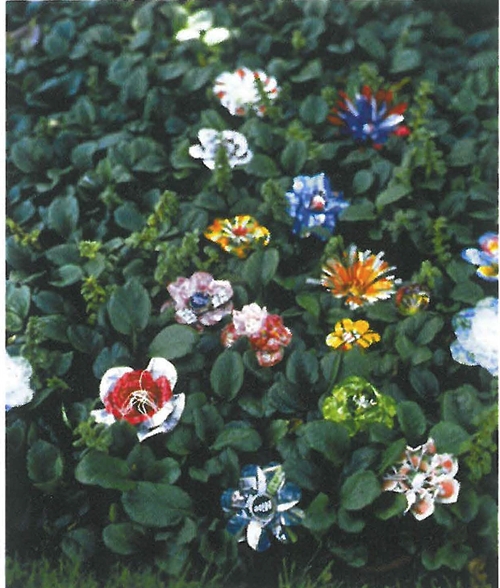

For these reasons, Fiona Hall's Cell Culture stood out in a largely technologically dependent exhibition, through the beauty and persistence of the human crafting of objects. Her witty taxonomy of part animal, part kitchenware creatures invoked not only the conquest of domestic science over kitchen disorder, but also the less-amusing historic use of glass beads as colonial currency in exchange for the Eurocentric classification of the world. Equally, both the work of Jason Hampton, and the enormous canvases of the Mangkaja artists' mapping of the traditional country of the Great Sandy Desert, asserted the living currency of Indigenous knowledge systems.

Much has been said about the prohibitive entry cost of the associated conVerge symposium. The great shame is that it was arguably the symposium that provided the real guts of debate, and the truly dialogic space proposed by the exhibition. By contrast, the art museum space and its continuing belief that the art object should be able to speak for itself compromised, if not muted, the political edge of critical debate through sheer lack of information for the viewer.

Was the objective of the exhibition to merely enjoy the artwork, or to interrogate it? The creativity that underpins both scientific and artistic practice stems from an essential curiosity; everything presumably begins from a question. Yet these questions, the problematic ethical messiness of collaborations between artists and scientists, even the very collaborative processes that created the work, remained largely absent or invisible. I wanted to know more about the scientists and thinkers who were acknowledged on artwork labels as collaborators. Who were they, and where were they? As such, the work within the exhibition risked being perpetuated as the apparent product of magical (and slightly mad) genius.

Whether conVerge succeeded in advancing critical debate for a broad audience about the synthetic and authentic futures of the social, the cultural, the biological, is debatable itself. But for those brave enough to enter its darkened spaces, it at least succeeded in creating a space of immersion and speculation in which to contemplate the place of art and self in these debates.