From virtually the year after their graduation Meredith Rowe and Georgia Chapman attracted attention for their printed textiles in Melbourne. Vixen textiles were all that theoreticians have claimed as the special proprietary of the crafts: the feel for materials, design based on function and substance, innovation tempered by knowledge of the tradition and properties of the medium, an art that was livable not rarified and theory-based. That two graduating students could position themselves rapidly at the head of a medium, and certainly reconceptualise and revitalise it, was an extraordinary achievement.

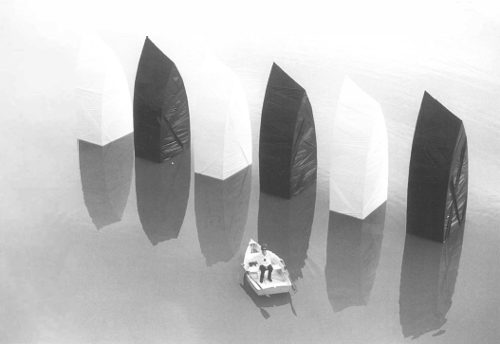

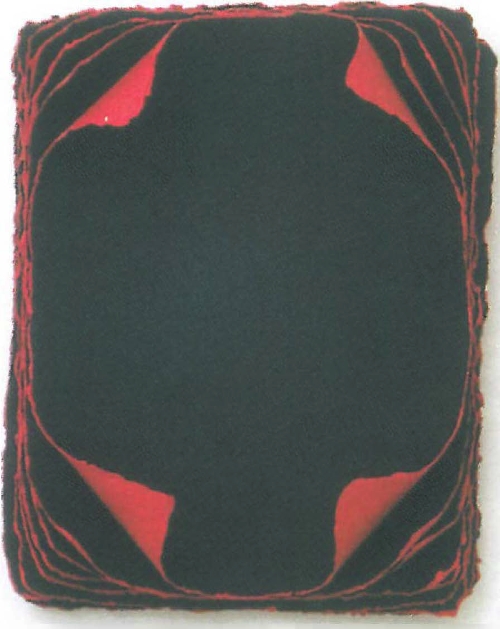

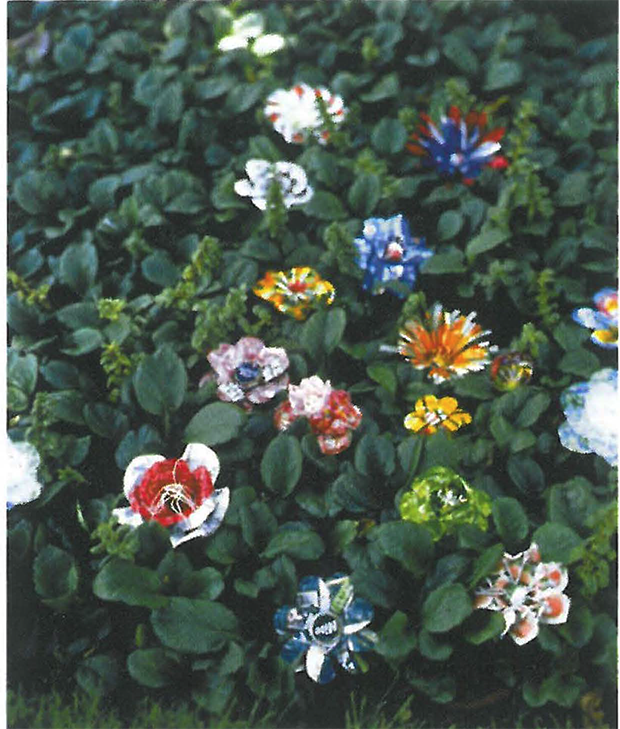

With the installation Notes From 2045 at Westspace, Meredith Rowe has repeated this success in another medium. Whilst perhaps not reconfiguring the whole genre of installation, as rookie sculptor/installationist Rowe has matched more experienced workers in this medium. From the smallest components of her printed textiles or the delicious series of lotus flowers made from packaging material to the working of the various configurations of the Westspace area (not to mention outplaying the neighbouring installation of visiting German feminist activists) Rowe's exhibition was a meaningful gallery experience, consisting of basically two room settings, one with a dining table set with mousepads printed with Rowe's photographs of urban scenes in Korea. In the other room finely printed and constructed items based upon traditional and modern garments and textiles from Korea were set out on a series of low shelves. A collection of fake peonies was mounted on the wall between the two main exhibition areas. As with her Vixen textiles, Rowe's fastidious skill as a maker, her eye for visual ideas and pattern, as well as a sense of getting down and dirty to find formats that can deliver effectively as product permitted to her devise something that is flawless to the immediate gaze. Perhaps I am biased, yet how could one resist an artist whose found objects from Korea included Hello Kitty embroidered Burberry check houseslippers?

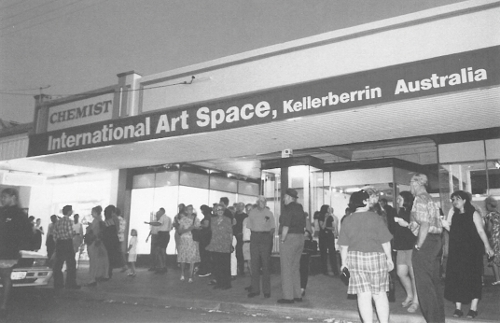

Notes from 2045 indicates that Rowe's movement towards Fine Arts was by no means tokenistic or shallow and also justified the decisions taken by various bodies, Asialink, Arts Victoria, the Australia Council and the Australia-Korea Foundation, who have funded Rowe's work and the recent residency in Korea which informed the Westspace installation. Vixen was no stranger to mainstream gallery space. Rowe and Chapman presented their farewell collection as framed pieces at Craft Victoria and were shown in many craft, design and textile-based shows at a national level. From being selected as a renowned craftsperson to establishing a presence in an alternative artist run space is a leap which Rowe made confidently.

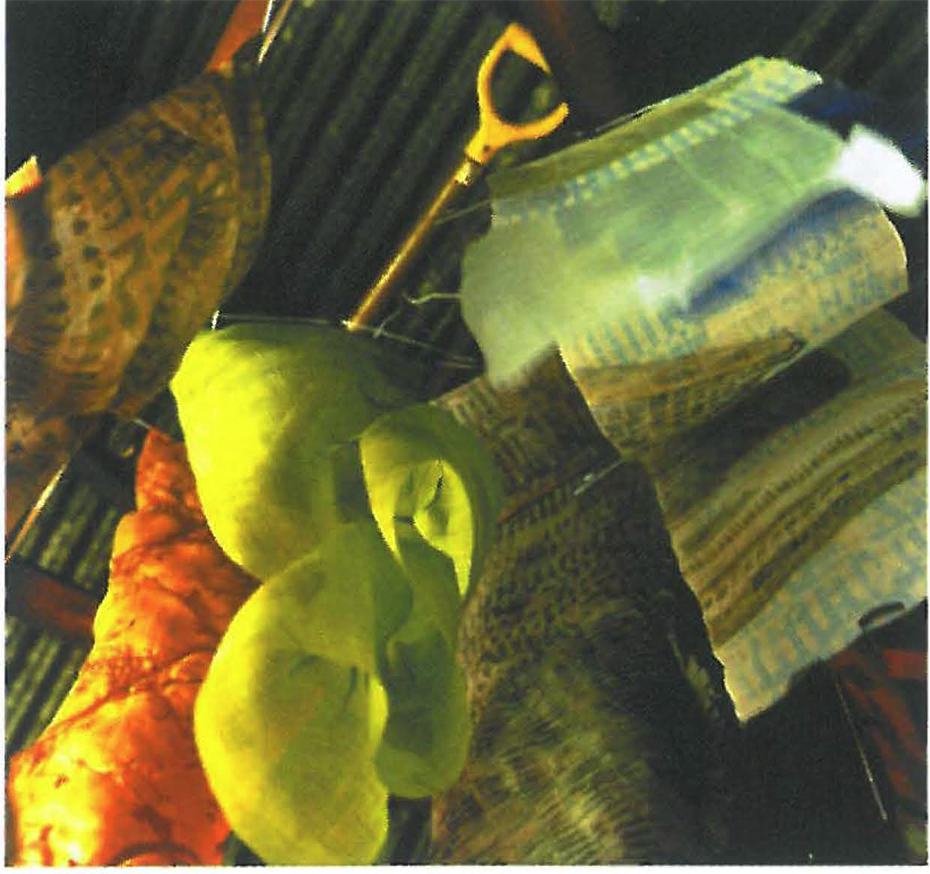

Notes from 2045 provided such visual delights as strange marriages of east and west, flowers made from packaging for Korean groceries and confectionery or a child's teaching alphabet in squishy foam plastic or the aforementioned Hello Kitty slippers. As in Rowe's textile practice there is a curating eye at work, selecting and assembling. But the exhibition did more than celebrate the strange chemistry when industrial production overwrites traditional craft formats or document the uninhibited inventiveness of Asian factories when developing consumer goods. It explored cultural identity and place: do white Australians laugh at the Asian other in misreading of the cultural lead of the centre, or does the margin reveal the corruption brought from outside and the meretriciousness of the supposed benefits of a global culture, or again, do the margins reveal the new formats and rituals of changing experiences?

The title also indicates an element of futurology. Is the garish spectacle presented in Rowe's photographs of cultural clashes and tawdry yet compelling disintegration of the urban environment the prospect before us all? Rowe's exhibition celebrated and introduced the strength of and survival of Korean formats and traditions alongside global culture. She used the space and the gallery fixtures to introduce a sense of contemplation and ritual that is often missing from the Australian everyday. Her meticulously reproduced objects, in patterned textiles and papers, garments and offerings were laid out ritualistically on small shelves, which were intended to be thoughtfully considered by the viewer, even the packaging and tying of parcels, were aesthetic offerings, informed by traditional practice.

Items were hung and mounted – as were her textile banners - to suggest visiting religious shrines and pilgrimages. Visitors were expected to remove their shoes and progress through the exhibition wearing house shoes. Her conceptual dexterousness and inventiveness when using space and location have expanded beyond her early craft practice. In the ricocheting of images and ideas from east to west, traditional to modern, found objects and artist-made, Rowe affirmed the survival of depth and meaning amongst the neon signs, the freeway overpasses, seen in her photographs or the commodification of identity seen in the child's play carpet, cut out with foam letters of the Korean alphabet. She was appreciative of but did not stereotype her host culture and explicated its relevance to a future where local and global elements increasingly mixed and coincided.