Australia's longest running and largest arts festival, Perth International Arts Festival, celebrated its 50th year in 2002 to the theme Air. The celebration however was muted in the visual arts. Slipstream - one of several mini festivals under the umbrella - was culled to a mere twelve venues - two of which were in the country and another in a cafe. A large proportion of these exhibitions was projection-based and others, while at times conceptually challenging, displayed objects that were often visually bereft. This left the 'unofficial' galleries to provide many patrons with their festival. Slipstream was saved by an engaging exhibition of social comment leavened with black humour - The Divine Comedy 'staged' at the Art Gallery of Western Australia.

In the early festivals the legendary John Birman accorded all art forms equal status with support provided to entrepreneurial gallery directors who brought out internationally significant artists. The scene was vibrant and local galleries and artists made a special effort. This changed with the directorship of David Blenkinsop from 1977 whose support privileged the performing arts, resulting in the visual arts component withering amid a mixture of controversy and apathy. Great expectations followed Sean Doran's appointment. He set themes, opening spectacularly with Water in 2000. A budget overrun saw his wings trimmed for the Earth festival of 2001. He made an effort however to reinvigorate the visual arts and put some fizz into the scene. Visual arts was made a separate entity and given its own director - who left before the 2002 festival opened.

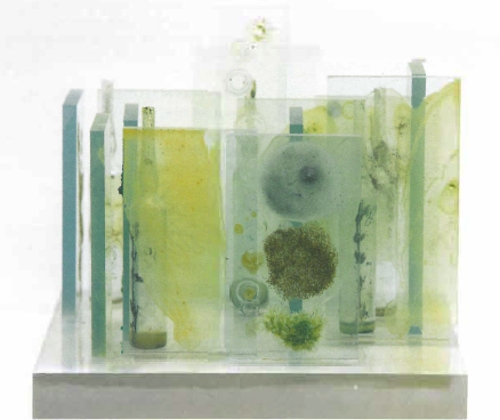

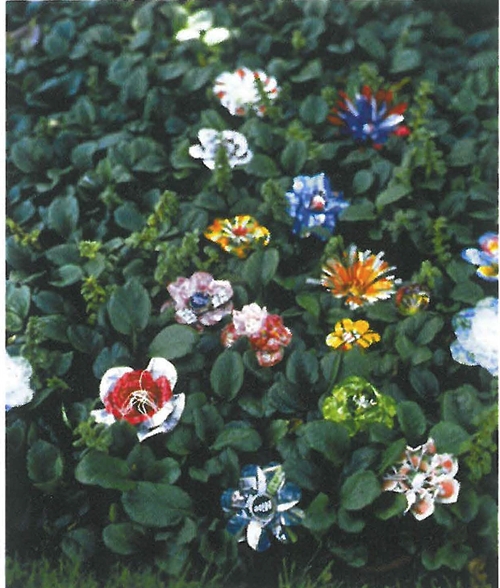

Few galleries bothered to support the theme. Filipino artist Alwin Reamillo's Semena Santa Cruxtations mounted by Fremantle Arts Centre, with its painted crab shells, was two years late with its water theme as was Lawrence Wilson Gallery's Deep Water/Aqua Profunda by Lyndal Jones, the companion piece to her other offering Spitfire 1, 2, 3. The Venice Biennale work was at first confronting and confusing with a multiplicity of images and sounds woven together and changing rapidly. It took time to adjust to moving images of Venice and Sydney patchworked across two huge screens to the accompaniment of a multi-layered, multilingual soundscape. However the installation repaid those with the time available to appreciate it.

Other time-consuming works which did fit the theme were the 57 minute Kitsune at John Curtin Gallery paired with Grace Weir's Irish entry at the Venice Biennale - Around Now - with its delicate images photographed into and away from a cloud. Joao Penalva's Kitsune was mesmerising in its depiction of an ancient forest landscape alternately revealed or shrouded in mists.

Only one privately owned space was included in the programme. At the Church Gallery British based Angela de la Cruz installed deliberately damaged paintings.

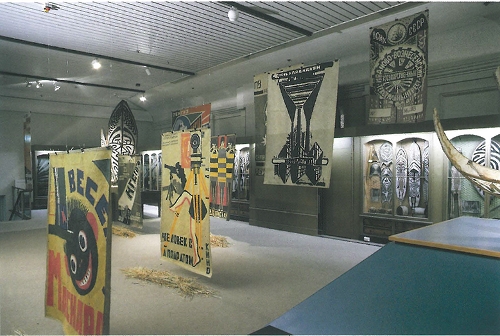

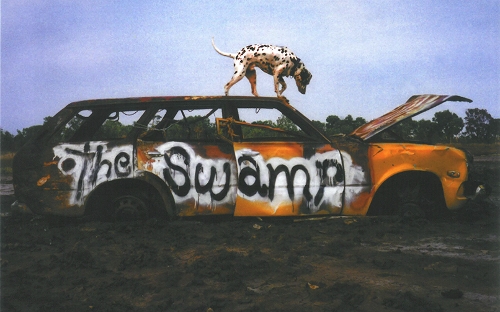

PICA's Elvis has Just left the Building, curated in Luxemburg, had eleven participants, selected from around the globe and charged with exploring urban legends. The works had nothing in common visually and lacked documentation necessary for connection and appreciation. Roland Boden's pine facade of a shed certainly needed more explanation. It was not readily obvious that the artwork was the photographs of the construction in other situations rather than the pine construction displayed. The more memorable contributions included Danius Kesminas' compacted car, commenting on Robert Hughes' brush with death in the Nor-West and Louise Paramor's Outback Heat carpet with its strong colours.

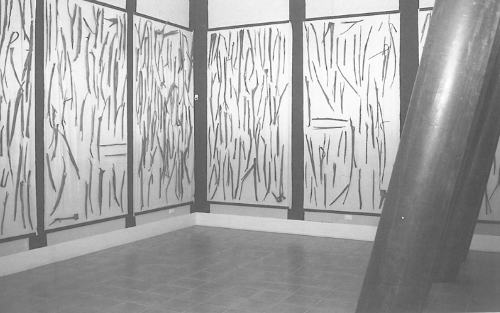

The show to see was at the Art Gallery of Western Australia. The Divine Comedy, which incorporated projection with print and sculpture, featured the engagingly energetic works of South African William Kentridge, several films from Buster Keaton and the well known Los Caprichios prints of Francisco de Goya, all trenchant commentators on the times they lived through. Kentridge is resident in Johannesburg, where he also works in theatre, as well as making drawings, sculpture and animated films. His shadow play using a number of his iron sculptures marched jauntily on the wall to the accompaniment of Lead me to the Lord in Prayer. In three dimensions they moved along a very long trestle in the gallery and delighted in their freshness. His animated films, each still made by overdrawing the previous charcoal sketch, engaged with immediacy and bite. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission on which one film is based is well known. He lightens his messages and considerable graphic skills however with a quirky humour incorporating touches such as his wondrously spiky cat which morphs into a radio, a reporter's tripod or a gas mask as the artist's fancy takes him. One event which really felt like a festival.