Points of Entry is an international touring exhibition of new media art developed on-line by curators, Nina Czegledy (Canada), Deborah Lawler-Dormer (New Zealand) and Robin Petterd (Australia). Whilst revealing a range of approaches to new media, we gain some insight into cultural exchange in a burgeoning global networked art arena.

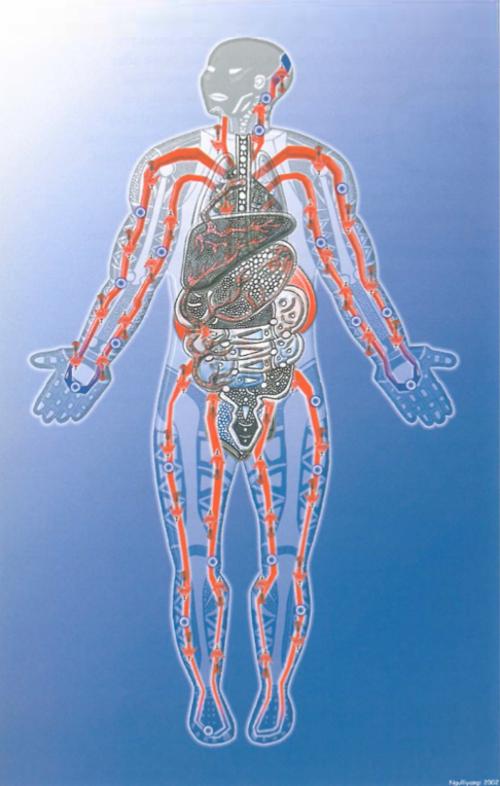

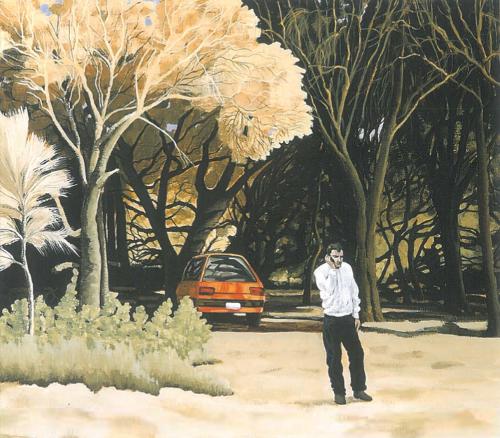

The exhibition reflects the complex communication technologies that increasingly dominate human interaction, but the work included is far from a compendium of cutting edge gadgetry. In referring to them as slow media, Robin Petterd suggests a stepping back from the gee whiz factor, getting off-line for a moment to ask, where am I? For these artists, the cycle of communication between humans through machines across the globe revitalises the cultural power-play between centre and periphery, at a time when we thought it might be safe to forget who we really are and where we might really be. After all, doesn't the technology surrounding us give access to information that crosses geographic and cultural divides through what seems a universal algorithmic filter? And surely the days of struggling artists on the periphery, who have to escape the cultural void they inhabit to gain any perspective of their worth, are over?

Instead, it seems the tyranny of distance hasn't been entirely alleviated, it has just changed. Even if communication occurs in real time across these divides we are still playing a game of Chinese Whispers, only now the game is infinitely more subtle, and separating the distortion from the message, more difficult.

Interactive potential in new media art is especially relevant to the larger context of communication technology but also to current rhetoric on the interactive decentring function of the artwork. But interactivity in art, as elsewhere, is never an equal dialogue or even necessarily benign. It depends on who's controlling the boundaries. We may be, (as Sean Cubitt writes in the catalogue) ...coming into...a new democracy where all of us recognise our interconnectivity, but this would be a vain hope if we can no longer recognise the boundaries that separate us, as well as the ties that bind.

Whether specific or more abstract notions of place are referred to in the work, it is the actual place where each work operates that most concerns these artists. If these works are not all, strictly speaking, installations, they are all theatrical time-based with a self-conscious interactive element. The fact that the gallery remains the centre of artistic veracity reveals an acknowledgment of the focus placed on being there in time. The point is that the work should not be regarded as integral to itself, and the artist not the centre of its creative potential. This temporal aspect once considered peripheral (Mid 20th Century Modernism) is now the central formal consideration for many contemporary artists. This being the case, the installation format, in dealing with real time and immediacy, presents us with the question of how relative this experience can be. Whose time and whose place is it?

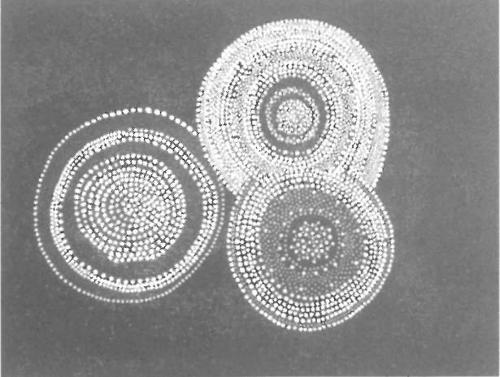

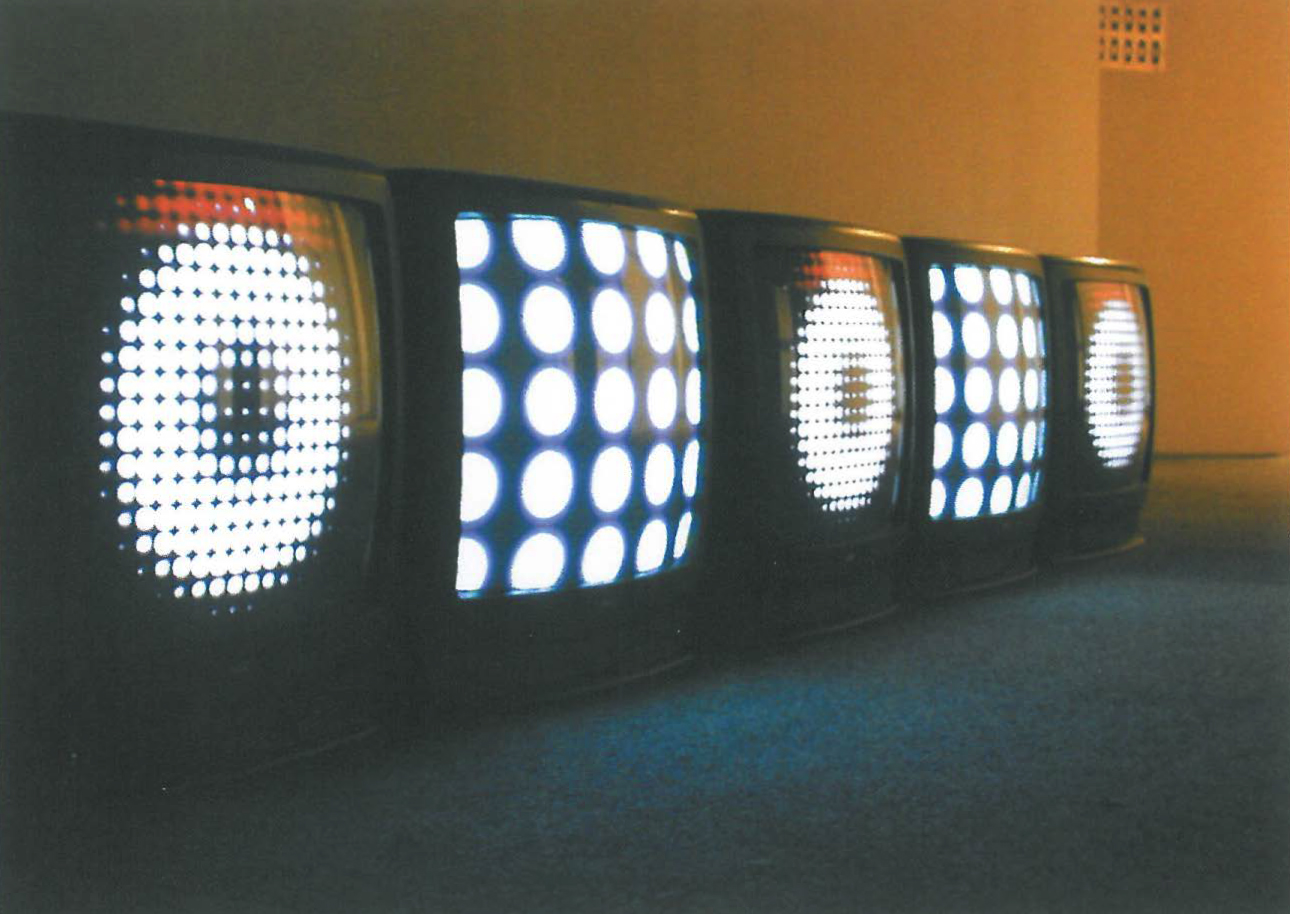

Andrew Burrow's Here comprises two small boxes with drawers that when opened trigger a recorded conversation between the two. Like a lament, Burrell writes in the catalogue, Perhaps here really is a place we cannot leave. Sean Kerr and Kim Fogelberg's, dot_iv, does its best to prevent you from leaving. Five TV monitors display repetitive, digital sound and shape that creates a hypnotic alien synaesthetic experience, in which there is the possibility of being transfixed in a disconcerting no-mans-land.

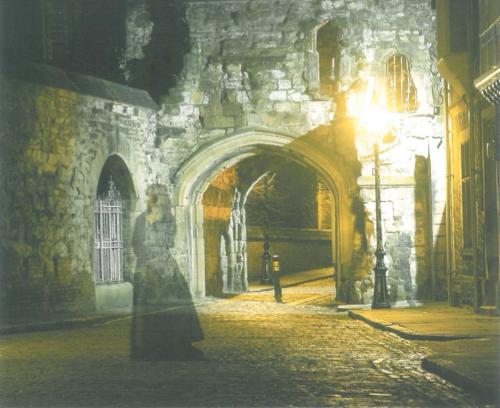

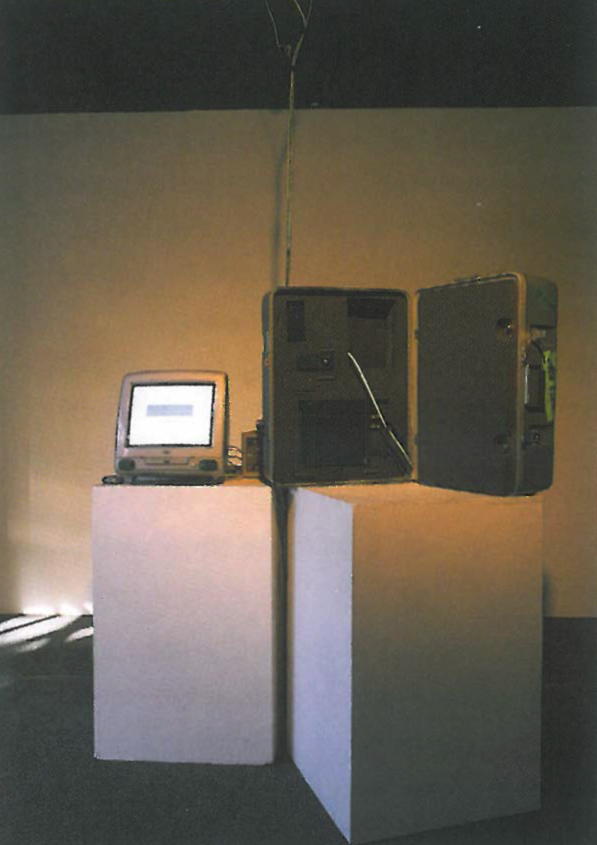

The possibility of immediacy itself becomes questioned in Leigh Hobba's, Red (v3). As the recorded sounds from a distant place bear witness to the artists having been there, the sound of two rocks actually clicking together (activated by pressure mats in the space as you walk on them) can be simultaneously heard from the speakers. The infusion of past and present cheats us of immediacy, as we are reminded that our reflexive consciousness is like a shadow that precedes the event itself. In this light Daniel Jollife and Jocelyn Robert's, Ground Station, ups the ante and brings into question the viability of the main aims of installation. Dispassionate piano sounds drift through a nondescript scene of a computer and an open suitcase towards the back of the space on a plinth. The banal is powerfully transformed by the realisation that these sounds are being produced instantaneously from a synthesiser linked to the tracking of Global Positioning System satellites. This data is ...processed by an algorithm designed by the artists, that filters and transcodes this into musical notation. Place and time become inconceivably contingent, outside any human recognition or medium. It delimits a boundary that cannot be broached and places the immediacy of the installation on shaky ground.

It is disingenuous in the extreme to believe that the interaction taking place in any installation could be infinitely inclusive, but if the decentring of place cannot be accommodated without compromise, then we must conclude that the methods used for interaction are at best successfully manipulative or at worst merely tokenistic.