In the national Parliament politicians are negotiating a free trade agreement with the United States. The race is on to get an agreement through before the summer break while this momentous matter has been reported in the media for a mere matter of months. If a free trade agreement is signed it will mean, in theory, that Australia loses its ability to subsidise its industries, as subsidies will be deemed to constitute unfair practice.

With the rapidly diminishing range of media ownership in this country the media have kept the issue low key. Faced with having to explain what will happen to the subsidies in the pharmaceutical industry which keep medicines affordable, unlike those in the United States, the government has made reassuring noises. So far so good. As far as subsidies to the arts are concerned, this has not yet surfaced publicly as an issue. We know that artists in the US receive very little government support, with private foundations being the major sources of patronage, an option which is not currently available here.

Without protection however, it seems absolutely inevitable that film, TV and music production will be overwhelmed by cheaper US content despite a compromise proposal to maintain quotas for Australian content but to peg them at current levels. Convergence of technology means that new modes of internet content delivery, as yet not adequately defined, could all too easily slip on to the negotiating table when trade-offs on beef, dairy and cotton are being made. While Arts Minister Rod Kemp has said culture will not be traded away, Trade Minister Mark Vaile is on record as saying that it is on the negotiating table - but only so that he can argue the case. Hmmm.

If, in the argy-bargy of negotiations, culture becomes a casualty, Australian contributions to film and television, as well as the more slippery online content will inevitably decline. It is frightening to think that Australian artistic expression, which at the turn of this century is just beginning to be recognised by ordinary citizens as an important means of creating our identity, is facing death by a thousand reruns pumped out by the leviathon which is the US entertainment industry. Quotas on Australian content in broadcasting could be frozen for the indefinite future at their current levels, and these levels, thanks to the cost of local production compared to cheap imports, and the long drawn-out budgetary squeeze on our public broadcasters, are lower than they could or should be. More imported programs than ever will flood the airwaves - Australian talent wasted, careers blighted, the brain drain revisited in a new guise.

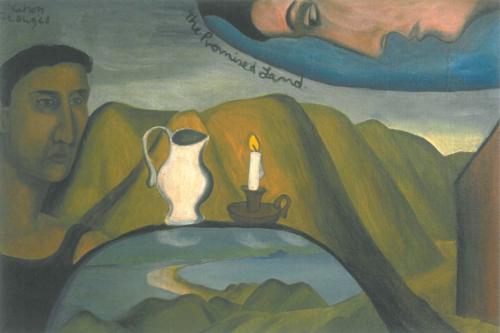

There is cold comfort in the fact that, apart from an undefined potential threat to arts subsidies, the visual arts, at least, may be proof against the deluge - galleries are not owned by transnational companies who prefer to market cheaper work by celebrity imports. With any luck, if public subsidies are protected, artists will continue to hoe the fertile row of the past two or three decades, the time when our place, always in the sun, but often perceived as the shade, was discovered by many inside and outside the country, to be both rich and strange.

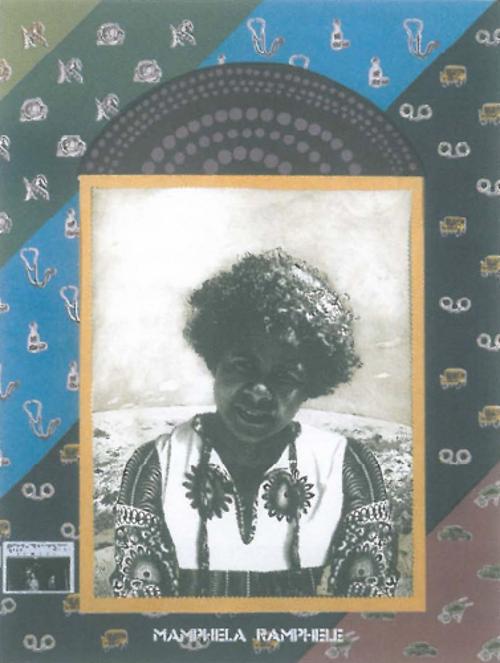

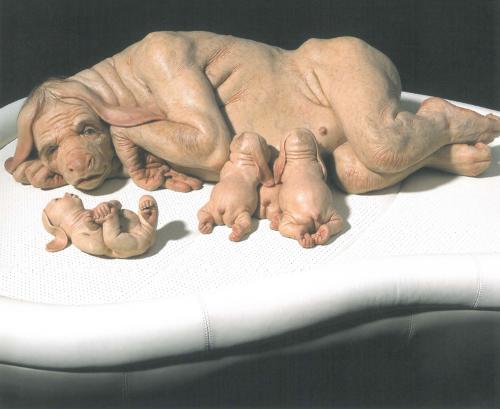

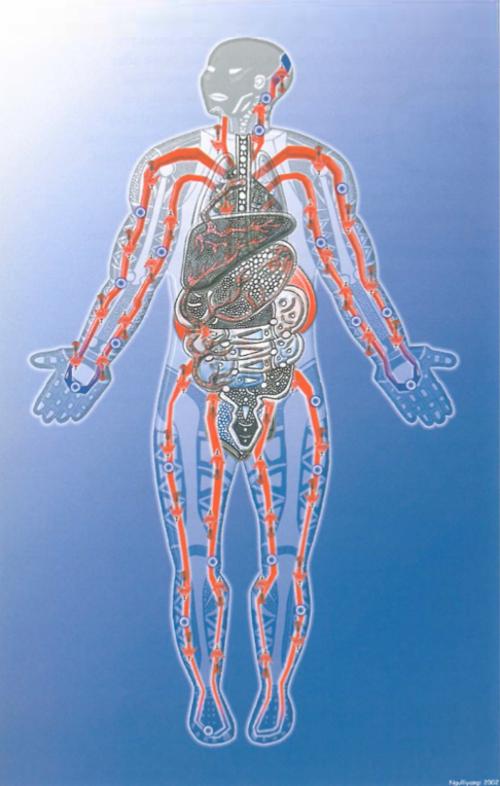

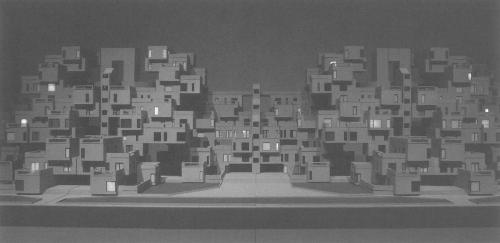

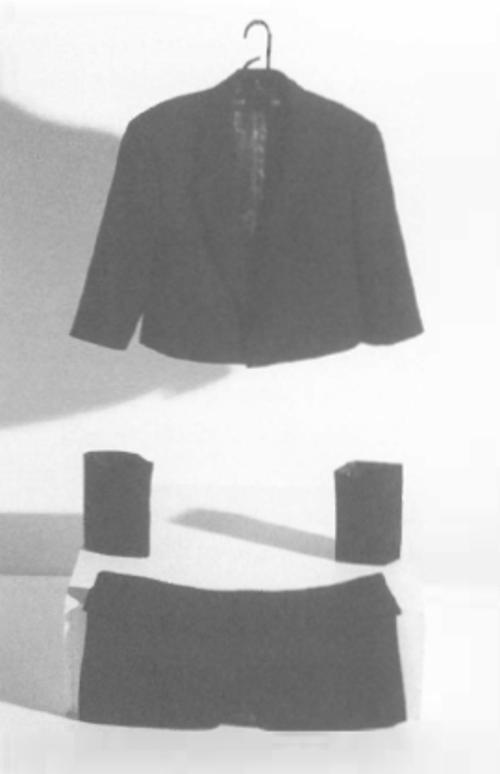

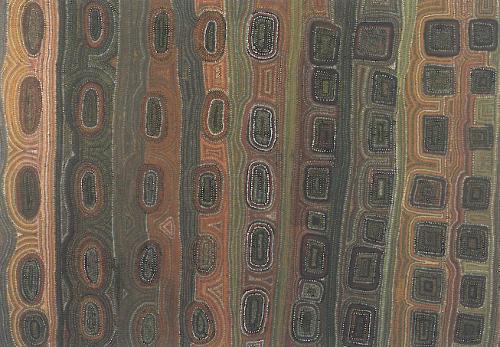

As if to illustrate the fact, this issue of Artlink is going to Berlin to celebrate a major exhibition of Australian art there, initiated by an international curator. Face Up: Art from Australia, showing at the Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin from 1 October, is large and ambitious. Juliana Engberg's preview looks at Susan Norrie's take on apocalypse in many forms, the immense power of nature as a dust storm sweeps over and paralyses a large city, a disaster caused by human mismanagement of the land; at David Rosetzky's depiction of the dysfunctional, lovelorn and lonely lost in the most urban/suburban society in the world, and Callum Morton's architectural recreations. Nominally unthemed, this issue of Artlink explores various veins of Australia's rich strangeness: Christine Nicholls shows us the phenomenon of Dorothy Napangardi's painting, an artist raised under the huge sky of the bush, stars for a ceiling; Peter Timms discovers David Keeling's changed perception of Tasmanian landscape, from wilderness to Japanese car in a clearing; Wendy Walker writes of Hossein Valamanesh who dreams the connections between the land, the mirror, the shadow – and Swiss Alps and the stockmarket; Australian deadpan humour is immortalised in Place/Urbanity, Jeffrey Shaw's brilliant installation about the districts of multicultural Melbourne. Shaw is back home after many years in Karlsruhe running new media organization ZKM and celebrates with this virtuoso, interactive ethnographic flythrough with laughs. Our expertise in biotechnology has spawned the hybrid beings of Patricia Piccinini which Tracey Clement compares with the superreality of Ron Mueck and his human family. A most significant essay here at this moment in Australian history is Stephanie Radok's The Meaning of Aboriginal Art. As an exposition of how we can grasp this phenomenon and its place in our world view it poses and answers many questions.

Our last two issues – Fallout: War Terror, Refugees, and Critical Mass: the New Brisbane have been creating ripples around the world. Our next issue is titled The China Phenomenon. It looks at the extraordinary success of Chinese art in the West post-Tiananmen, and continues Artlink's documentation of Australia's engagement with the Asia-Pacific region, ultimately the most important factor in our future.

NOTE: All who are concerned about trading Australian culture for agriculture should write urgently to their Federal member, to the Ministers of Trade and the Arts and the Prime Minister.