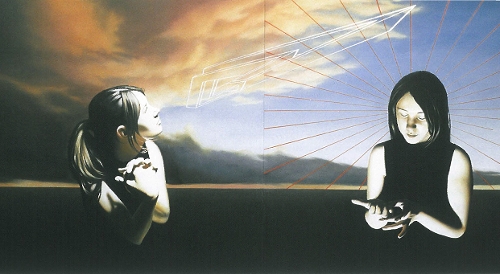

Some exhibitions proclaim themselves as outstanding experiences as soon as one enters the gallery space and others gain deeper resonance in the light of hindsight and later events. Lily Hibberd's video and painting installation Burning Memories did both. It immediately struck the viewer as an exhibition which loudly proclaimed the survival of brush upon canvas, despite so many forces, fashionable and technological, ranged against painting pure and simple. It also packed a singular emotional punch for a solo show of recent works. This poetic, deeply evocative and stirring exhibition of undeniably beautiful paintings and videos took the viewer into strange and unsettling emotional territory, precisely because of the seductive and aesthetically resonant qualities of the paintings and anthologised video clips. The viewer's unease and guilt was increased by the lyrical formal qualities of the works on show. Burning Memories was a useful reminder of the simple power of even old media. The unsettling concentric refractions extended as far as mainstream cultural narratives and preoccupations of Australian (white) self-imaging and society.

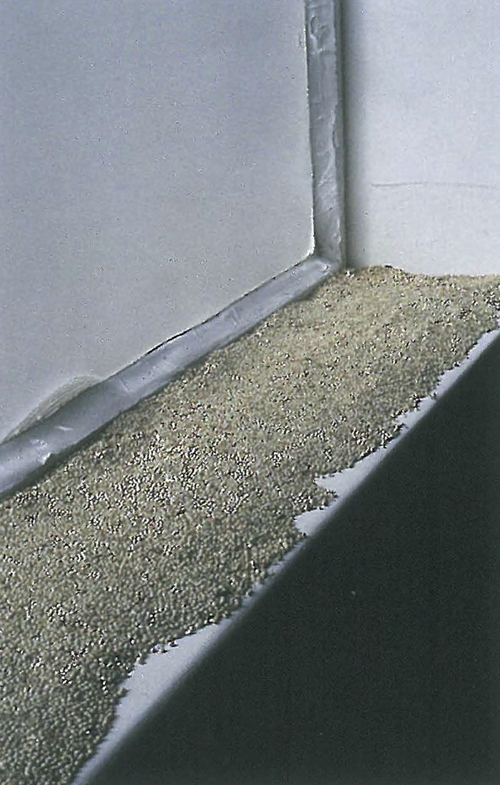

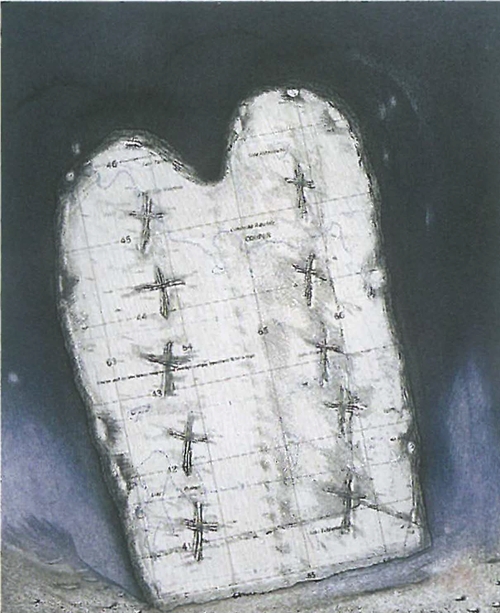

It was an exhibition that proclaimed the luxuriance of emotions that pure aesthetics can raise. Burning Memory's impact derived from the visceral impact of the subject, fire, especially of domestic homes and the physical qualities of the components, especially the appealing and accomplished qualities of oil paintings. On pure academic grounds the paintings were some of the most suave and assured that I have seen in recent months. The skills were flawless handwork in observation of the subject and translation into paint. Who says that today's artists 'can't paint' a 'recognisable' subject?

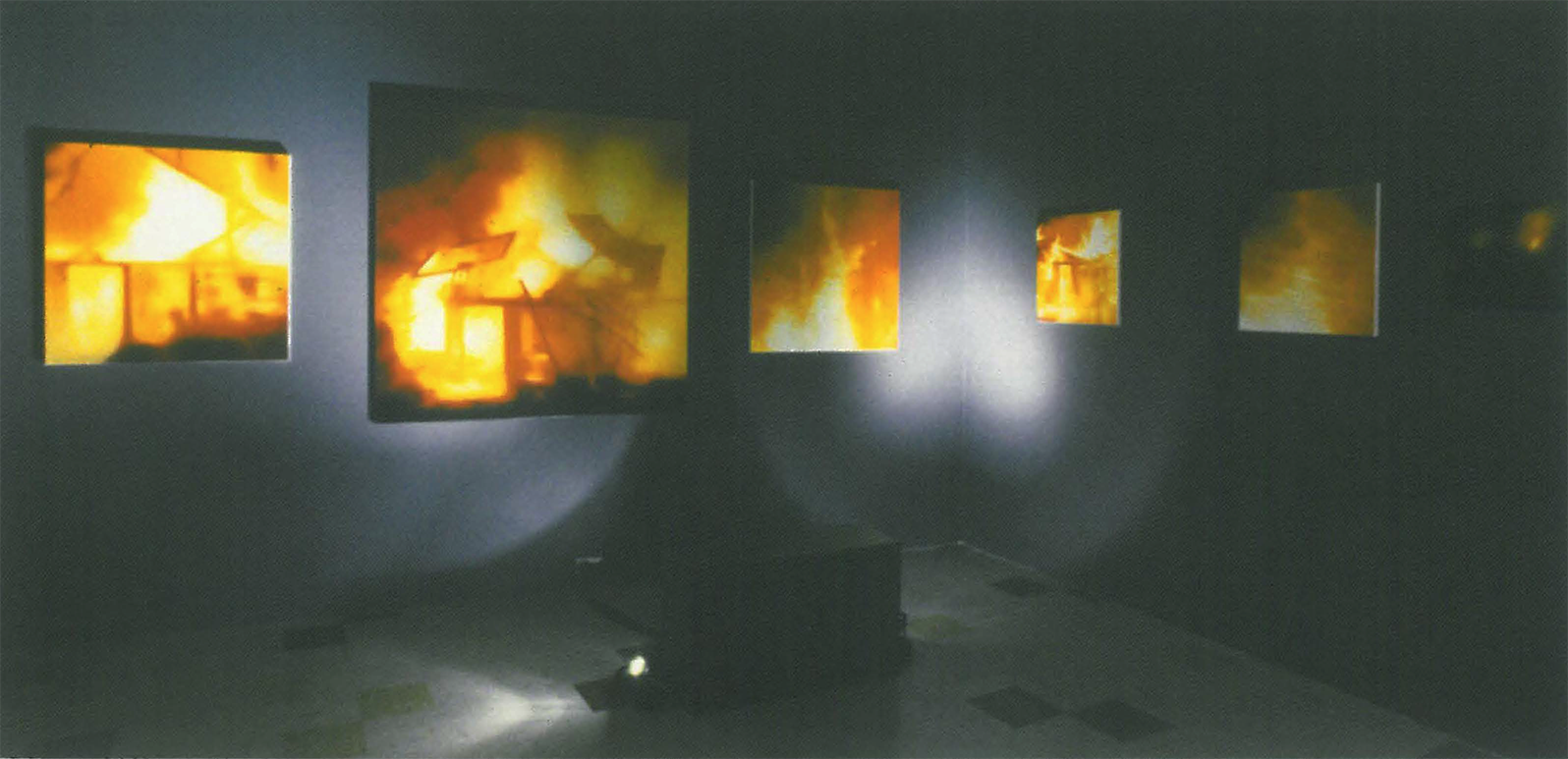

Even coming to the exhibition was strange and remarkable, walking up narrow, dark stairs back stairs through an invisible wall of hot air that settled on the stairs and in the gallery, (to the discomfort of visitors and staff) created by unlicensed building works and a dodgy installation of refrigeration units by other occupants of the same building, then into the expected white of the front part of the gallery and finally into the darkened space of the back gallery, illuminated by glowing luminous paintings in reds, orange and whites and a video loop of fire scenes in colour and black and white collected by Hibberd - repeated images of fires from the Australian news media and also classic films, including that penultimate scene in Rebecca of the necessary conflagration of the formidable Mrs Danvers, and her strange passions for the decadent and justly dead Rebecca.

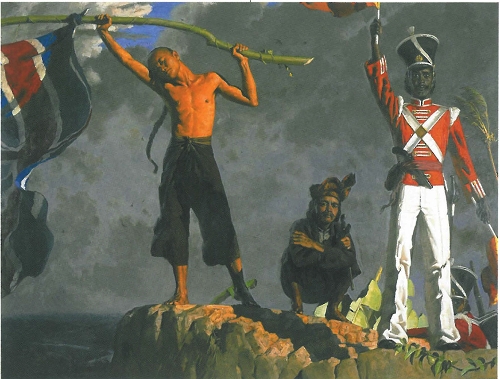

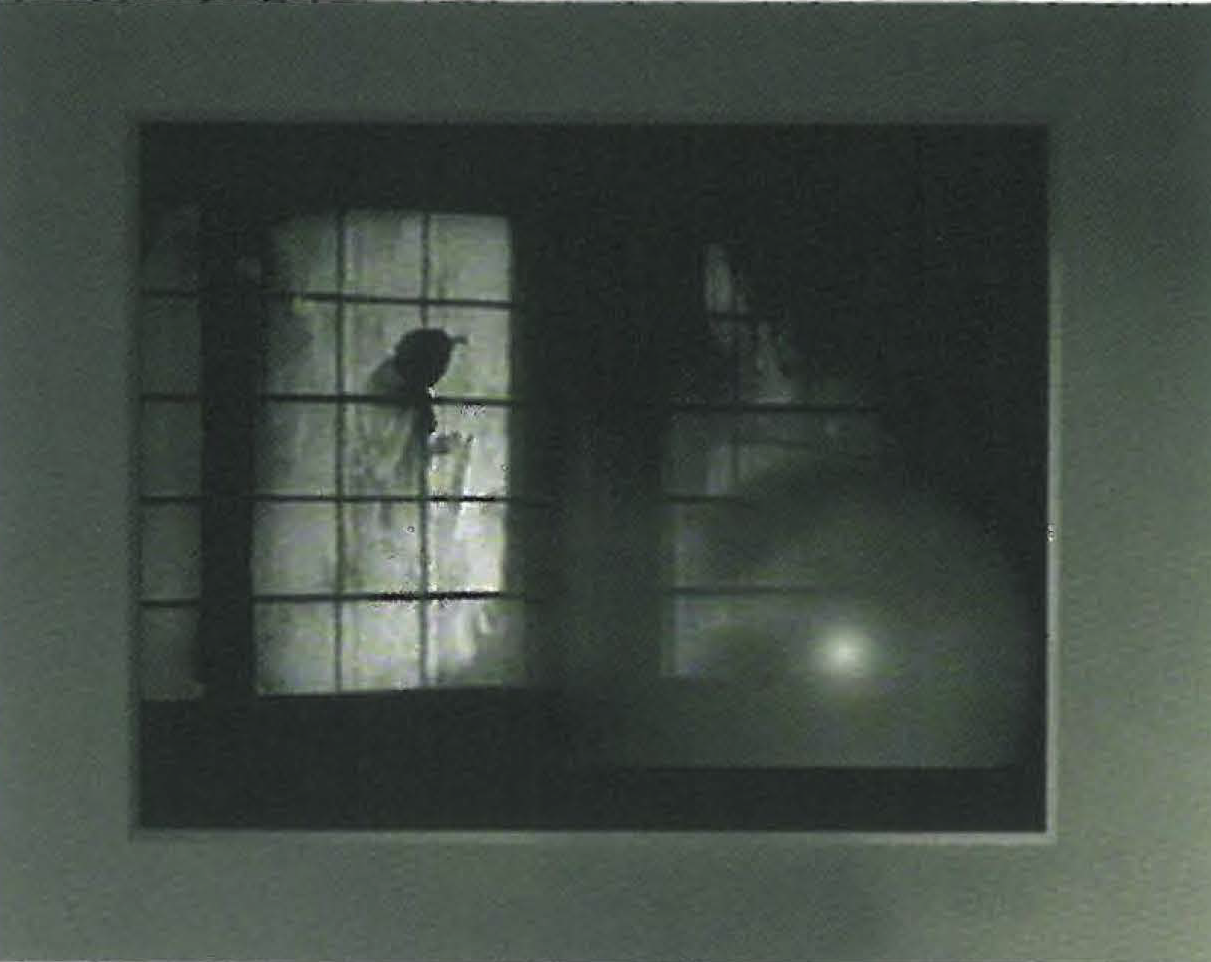

The formality of Mrs Danvers' hairstyle, the lesbian dominatrix who doomed herself earlier in the film by stroking the dead Rebecca's underwear as it lay in her wardrobe doors, and the grand, stately house English furniture suggested an unreal balletic atmosphere in the whirling flames and the scene of the woman swept along before them again and again. The paradigmatic elements suggested how tragedy so easily can be formalised into an aesthetic pleasure, how the media aestheticises the raw and rough elements of remembered life and emotion, and the questionable morality of drawing pleasure from misery. The dancelike mobility of the flames in these clips of the fire videos was compelling: fire would have to be a dream subject for video or film in its liveliness, mobility and speed. The intense contrasts of colour, light and luminosity also commend fire as a subject to light-based media. All the more remarkable that Hibberd then sets herself the painterly challenge of capturing these instantaneous impressions, the constant mobility and the tonal complexity in meticulous, luscious oils, with a perfection of touch. She meets this challenge without hesitation. Turner's ability to render natural elements as light and colour-filled abstractions, his attempt to capture the ineffable and indescribable in materialistic paint and canvas is clearly an important point of exploration. Hibberd's works are both abstractions about light and movement and documentary scenes of an almost heroic grandeur and tragedy: the family holiday home as Raft of the Medusa.

Burning Memories would have justified a review on these grounds alone, but it has gained even more profound resonance and social-critical weight in the wake of the extreme events of the summer of 2001/2002. As much as the bushfires - horrific as they were - the stratagems of the popular media stay fresh and vivid in one's memory. The nightly news programs in particular ran viewers across a gamut of emotions and hyperbole, from the reality of some of the worst fire conditions in recorded white history, and the potential environmental catastrophes at sites such as the Royal National Park to the abjection of weeping homeowners, the 'keep your thumbs up and say it's ticketyboo,'coz tickety boo means things are alright' blitz mentality of the evacuations and overnight sleepouts, the firefighters as valiant ANZACS fighting against impossible odds, and - penultimately - rescue by Elvis the helicopter, proof if one was ever needed, of his divinity in popular imagination and also a crude indication of that Australian popularist reliance upon the U.S.A. as saviour that enrages elite intellectuals. Any consciousness of the 'real' emotions that may have been experienced at ground zero were overwritten by the media's fascination with set pieces and narration, and the uses of narration to define and grasp a story. Lily Hibberd's exhibition centred upon ideas found in her M.A. undertaken at Victorian College of the Arts, which explored issues of memory, the loss of memory and the manner in which film can overwrite and replace memories, engaging with ideas raised in text and art by Deleuze and Richter amongst others. Fire was partly a means to examine these issues, but it has a life/death resonance of its own, that Hibberd clearly responded to in this show.

Before the New South Wales bushfires, Burning Memories had already raised issues about the strange relationship between the cost of fire in Australian experience and the media's fascination with the hypnotic dance of the flames. Who could blame the media? The video clips that Hibberd had compiled were compelling. Her quest to capture news footage of fires had also inspired friends and colleagues, who began taping extracts from the evening news, so they became co-conspirators in her aesthetics of danger. In terms of what place fire has in the Australian creative memory, think of those Victorian set pieces such as Strutt's Black Thursday, Longstaff's Bushfires in Gippsland, and the lesser known lost 1890s work by Theo Hanson - a Heidelberg School artist Burnt Out. Early twentieth century poems and films also deal with the impact of bushfires in rural communities. Hibberd's show illustrated a familiar fate of cultural experience but one that has been relatively infrequently drawn out with such skill. Media reportage of the recent fires brought out these issues of the seductive fascination and the hypnotic orange swirl of the flames. Already Hibberd's show had brought the viewer to confront and consider the issue of the strangeness of fire scenes - through her compelling and perceptive representational paintings. We are confronted with the vulnerability of materiality, as well as the archetypal sacred, magical aspects of flame as edge experience and transforming force, which can be considered at leisure in an art installation - the transience of perceptions, the fragility of being, alongside the more sordid emotions of vicariousness and sensation, as peddled by the media, and the deeply personal costs to the victims that each of those hypnotic clips and grand oil paintings represented.