Last year Nexus added to its growing reputation as a catalyst for original and creative approaches to multicultural programming in the visual arts and crafts. With a program inspired by a conversation between Hossein Valamanesh and gallery director Mirna Heruc, Nexus' curators brokered a collaboration between three artists of diverse backgrounds and focus – Melbourne writer Mammad Aidani, Perth/Singapore installation artist Matthew Ngui and Launceston textile artist Greg Leong. Working with the curators who selected them, their brief evolved through conversation and workshopping. The resulting ensemble of pieces had an immediacy that was refreshing and enjoyable and if there was any lack of coherence it was perhaps only because of the 'forced marriage' that begat it. Nevertheless, the overall success of the collaboration suggests that Nexus should maintain their mission of brokering such partnerships and promoting cross-culturalisation.

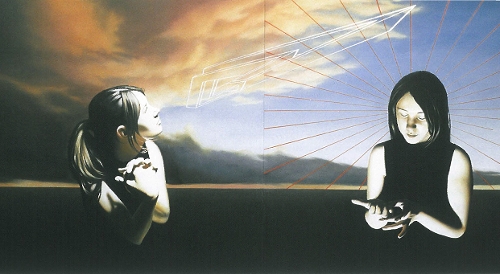

On the surface, the three artists explored the six centuries' old science of perspective and modern video technology to re-present ancient arts of calligraphy and textiles. A key device was that of exploiting the controlled perspective view provided by a fixed camera angle. This achieved effects ranging from the incidental dissolution of a wall into a whiteboard to the essential image in which the obscurity of exploding lines on a solid wall were turned into formally presented virtual text. This play with technique could have been strained, but its (fundamentally simple) play with the context of text worked as part of a larger goal to seek fresh expression of cultural diversity.

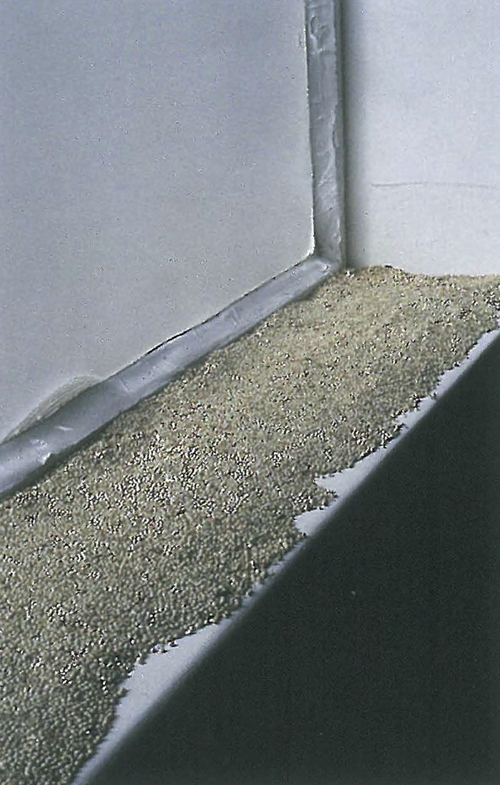

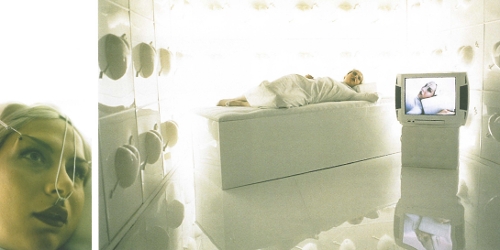

Entering Nexus (which deserves a more visible and inviting location!) one was confronted with a TV monitor that placed the arriving viewer in the picture. Curiously, that picture included a small rectangle of something that overlaid the viewer's own image. By the time one reached the last part of the installation it became clear that the rectangle was a postcard-sized piece of interwoven threads pinned on a wall; returning to the entrance to depart, the threads of the exhibition did indeed feel as if they were being drawn together.

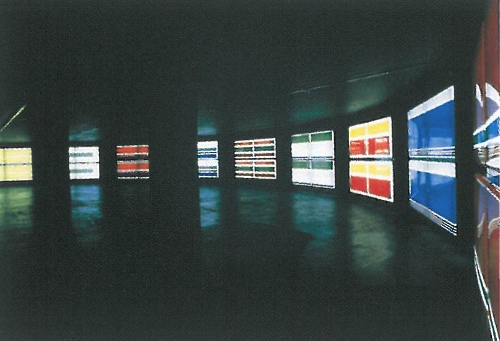

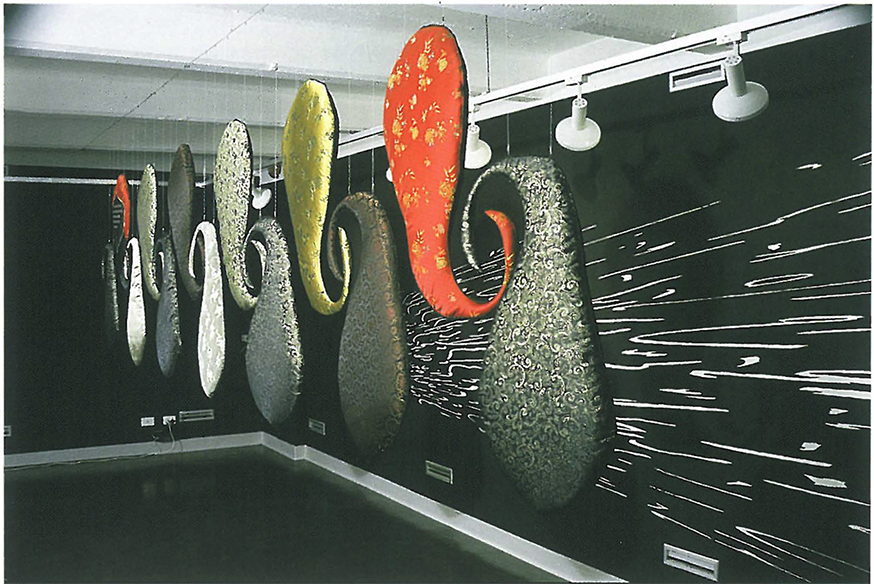

Entering the gallery space proper one saw distorted Persian text as a powerful pattern of dynamic lines exploding across one of the gallery walls. Exploring further, one discovered the dislocated verses of the poem scribbled across the back of 13 embroidered cushions hanging in a line through the centre of the space. The cushions were in the shape of a traditional Persian carpet motif called a boteh. The unlikely image of curlicued cushions suspended in space drew the attention of the viewer whilst the otherness of the cultural content was reinforced by the exploding scrawl of text on the wall running parallel to this formation of flying botehs.

Turning the corner, electronic technology was again made obvious by a projector set in the centre of the space. It projected an image on the furthest wall of a square of text, the same that sprawled across the wall beside the cushions.

All the Persian calligraphy was roughly brushed, perhaps to underline its robust nature as an alphabet with thousands of years of use, and certainly it made it less precious – this was calligraphy as a working tool rather than an exquisite, precise medium of reification. There were word games at work throughout this whole enterprise (the title betrays that much) but I doubt that any one observer could have discovered all the trickery in one visit. There were too many layers of play and this deceptively simple exhibition deserved repeated viewing to enable any observer to read the whole of the text. Perhaps any work that is built around text will cry out to be deciphered, whether or not that might be the intent, but it conveyed a strong sense of meaning something even if that meaning was opaque.

Words were at the heart of the exhibition, yet most visitors would have only been able to read the short piece in English that was a translation of one of the verses in a poem by Aidani.

In the depth of this room

Under the skin of the air I see,

Something moves dancing

From this space to greet

The other end.

The verse provided a point of contact and bearing for non-Persian viewers and readers - but is it possible to discern the correct syntax for reading when the words are mostly foreign and the set, or sets, of rules may be drawn from many places?

This exhibition was small, intense, simultaneously transparent and opaque in its meaning. Although the complete work was clearly intended to provoke and encourage rumination, the imagery was all attractive and accessible and so it worked perfectly well as a simple visual delight - but remained imbued with the carriage of lingering mystery and depth. I think that this kind of attractive challenge is just what is needed to bridge between the arcane and the workaday. The citizens caught up in the devastatingly powerful dynamics of popular culture need to be able to connect with the thoughtful and playful explorations of contemporary art. At Nexus, Aidani, Ngui and Leong transcended difference to celebrate commonality, without reducing the richness inherent in each of their participating traditions and talents. I look forward to seeing these and other artists and this gallery continue to build bridges within and between the cultures that are shaping modern Australia.