__Ali Gumillya Baker I write from unceded Kaurna Yarta, near Karra Wirra Parri (River Torrens).[1] I honour Kaurna Peoples and my ancestors and all Mirning peoples from the Nullarbor, and I acknowledge all First Nations Peoples of the Earth. In this edition of Artlink Indigenous: Visualising Sovereignty, deadly sister Paola Balla and I have had many conversations about the importance of seeing and reading Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander creative voices. As Bundjalung novelist and journalist Melissa Lucashenko reminds us, our ‘writing is a sovereign act,’[2]

Let’s rejoice in the wholeness of our families, and be careful to focus on what we have in common as First People, not what has been created to divide us from one another. Let’s practise what our Law tells us, and let’s keep going with the project we have as Black writers—to pay attention to what’s going on, to talk straight about our lives, and to remember to celebrate our beauty, our humour, our power, and most of all our land.[3]

This issue is dedicated to First Nations visual sovereignty, our creative ways of being, our visibility and voices in times when collective imagination is deeply impacted by ongoing political and environmental crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic. Meanwhile, the attacks on blak bodies within settler-colonialism continue. We continue to seek justice for our Country and for all it supports, living and non-living, once living and future living. We choose to reflect on our collective resistance, intergenerational survival and ongoing sovereign refusal.[4]

Indigenous sovereignty as observed by American/Chickasaw Nation citizen and scholar Jodi Byrd is located and relational; as such it cannot ever be fully expressed in words or fixed Western frameworks of law. Our sovereignty, as the knowledge of our Elders, senior knowledge holders and artists remind us, is breathing living movements across and through country, sky, water, time and space. Our sovereignty is collective and uncontainable, and in its very being is fundamentally a threat to the individualism enshrined in the settler-colonial construction of state. As Byrd says,

Chickasaw sovereignty is, according to our national motto, unconquered and unconquerable. It is contrary and stubborn. But the creases of Chickasaw movement demonstrate how sovereignty is found in diplomacy and disagreement, through relation, kinship, and intimacy. And in an act of interpretation. To be in transit is to be an active presence in a world of relational movements and counter movements. To be in transit is to exist relationally, to multiply.[5]

__Paola Balla I write from sovereign unceded Boon Wurrung Country and Wurundjeri Country of the greater Eastern Kulin Nations and from the city of Naarm/Melbourne. I welcomed the invitation from my deadly sister Ali Gumillya Baker to co-edit Artlink in solidarity and shared respect for our sovereignty as Mob, and in respect of the sovereign scholarship of Jolene Rickard—visual historian, artist and curator of the Tuscarora Nation (Turtle Clan), Hodinöhsö:ni Confederacy. Inspired by Rickard’s articulations of Indigenous visual sovereignty, I looked forward to dialogue with Ali, and the writing of Blak and other First Nations artists and critics in asserting our sovereignty through visual ways of knowing, being and doing.[6]

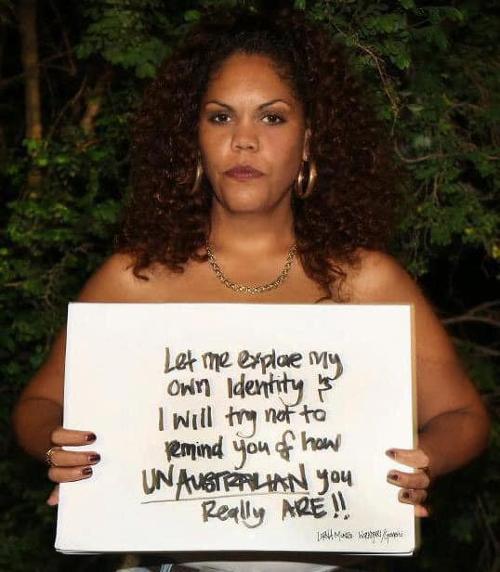

This is Blak work, and I emphasise Blak with the C dropped as named by artist Destiny Deacon in the 1994 exhibition Blakness; Blak City Culture! curated by Hetti Perkins and Claire Williamson at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art. By taking up Deacon’s blak, we continue to disrupt the status quo of those who shy away from the C word. Destiny spoke it into reality when she recalled being called ‘little black cunts’ by racists when she and her siblings were growing up in Melbourne. In using Blak, we are positioning the power of Blak womanism and Blak sovereignty. We also acknowledge the work of Aileen Moreton-Robinson in her seminal 2000 book, Talkin Up to the White Woman (reissued in 2020 with the extended title, Talkin Up to the White Woman: Indigenous Women and Feminism, 20th Anniversary Edition). Towards an Australian Indigenous Women’s Standpoint Theory: A Methodological Tool, (2012) is another key work for us.

In her empowering lecture ‘Indigenous Visual Sovereignty’ for the Power Institute in 2020, Rickard foregrounded a sovereign Haudenosaunee standpoint.[7] She expanded in discussion with Yamatji scholar Dr Stephen Gilchrist that when working with neo-colonial cultural institutions, we as Indigenous people need to remind the institution that the fantasy we were captured and colonised remains alive in the minds of the colonisers. As Rickard states in her talk, they fail to understand that ‘we are the future, and that our way of understanding how to be in this world has brought us to the place that we’re at.’

Knowledges, histories, lived experiences, of the sovereign survivors drive ontological approaches to curation and art making. As Rickard said, the Hodinöhsö:ni have maintained their sovereignty through epistemological ways of being in the world, and ‘our success at being Indigenous.’ She refuses the narrative of being ‘captured and colonised,’ and as this issue’s writers assert, (after Rickard), ‘we certainly interrupt that with our art.’ As Blak artists, curators, researchers and writers we express our sovereignties in public realms of dialogue that disrupt white ways of knowing us.

Sovereign love as resistance and collective care are connected to both curating and editing as acts of care. For Blak works, deep attention needs to be paid to Country and stories of Country, and all it holds, including trauma stories and how to respond to ongoing colonial racism and violence.

Commissioning and editing other Aboriginal writer’s work is a process of care, of facilitating the difficult work of dealing with the whiteness of organisations and institutions. We have to hold the line, to place and protect work that upholds our ethics and accountability to community with respect. This is where Blak critical art writing is crucial and necessary, and where Artlink Indigenous has filled an important role in providing a key platform for our writers.

In Visualising Sovereignty, the artists, writers and collectives are situated in sovereign political practices responsive and responsible to Ancestry, Country, family and communities. If we understand visualising sovereignty as a part of the work of de-centring whiteness in the colony, we are asserting Blakness, and Blak beauty in how we see ourselves. We do this without replicating harm and the patriarchal, heteronormative lens, so it becomes a tool to critique the colony and its violence and denialism. Valuing the work of Aboriginal artists as visual authors of Blak lives, without white editing and curating as a central controlling factor, the work can be read as visual sovereign maps for the future, telling truthful stories of this time. Blak art and art writing have important roles to play in asserting our sovereignty and reclaiming our stories. Blak spaces for sovereign imagination are important, and as award-winning author Alexis Wright wrote, ‘imagination is central to the meticulous struggle to be…this is the weight that infiltrates everything we try to do, the burden in all creativity, the handicap in vision.’[8]

%20Weaving%20in%20Rosie%20Kuka%20Lar%20(Grandmother%E2%80%99s%20Camp)%2C%202021%2C%20with%20Rosie%20Tang%2C%20Untitled%20Wallpaper%2C%20image%20c_%201978%2C.jpg)

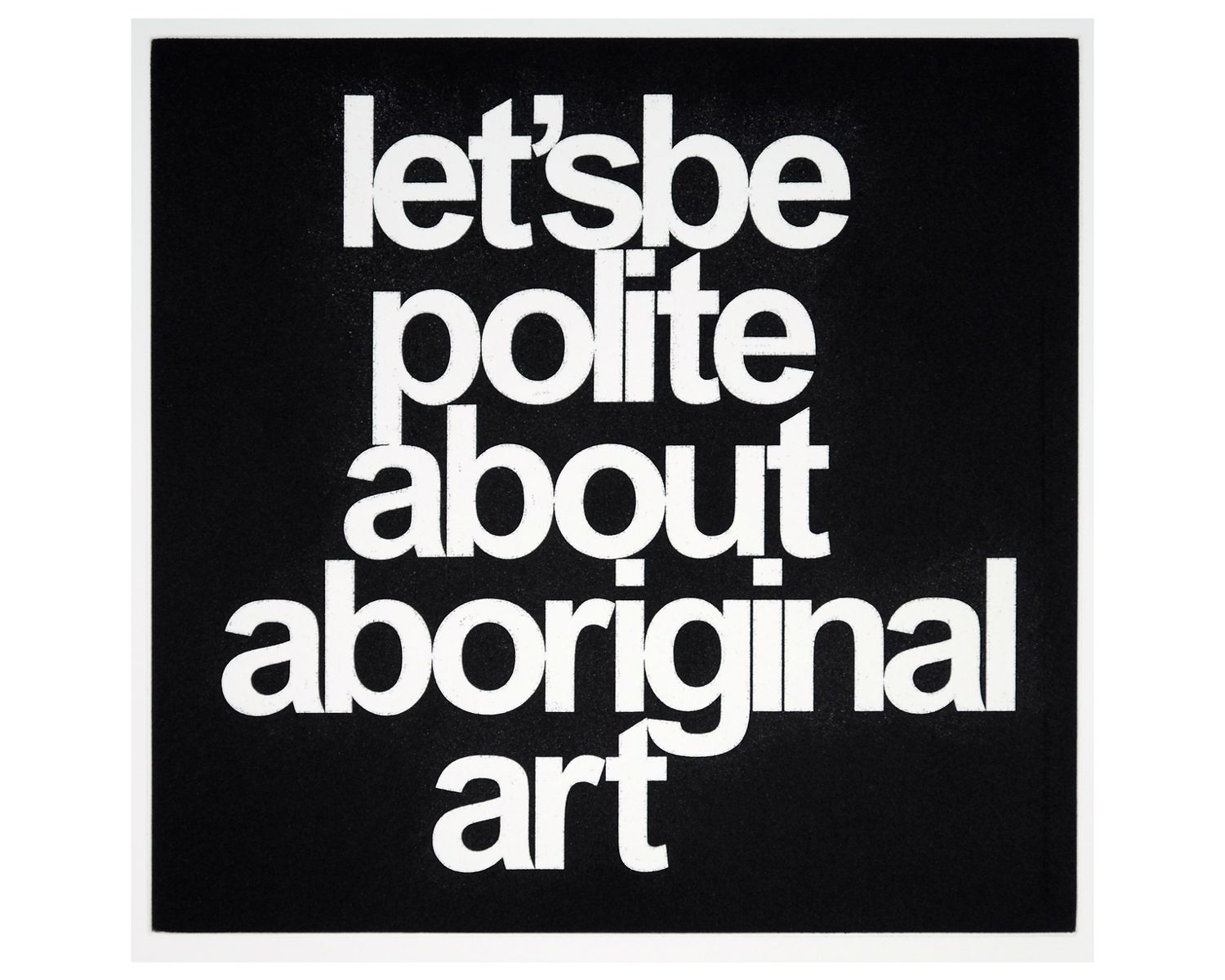

In Visualising Sovereignty, we start our assertions by drawing on the Blak archive and debates raised in Artlink Indigenous: re-visions in 2013. Here journalist Daniel Browning reflects on the continuing importance of genuine blak-on-blak art criticism while balancing care and community. Also putting art criticism into practice, Ali Gumillya Baker addresses recent work of Julie Gough, an artist who has upturned the colonial archive and its fictions to remind contemporary audience of massacre and land theft.

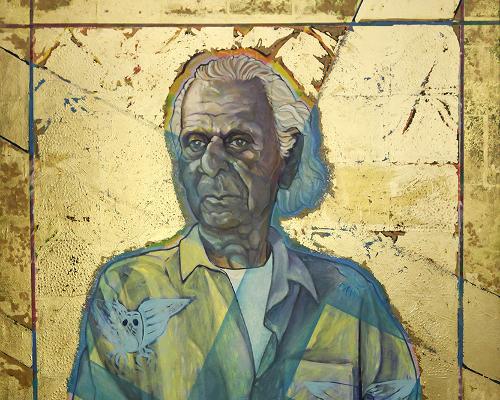

Paola Balla was honoured to have a conversation with curators Belinda Briggs and Shelley McSpedden about Lin Onus: The Land Within and their collaborative approach to this important exhibition just opened at Shepparton Art Museum. This issue’s cover image Barmah Forest (1994) by Lin Onus is a tribute to the sovereign love and legacy of his works from the Aboriginal Advancement League and to his return to Yorta Yorta Country. We also learn of a ‘sovereign sight’ approach as curator Kimberley Moulton describes her collaborations at the intersection of historical archives and artistic practice in responding to and activating museum collections. She also speaks to connections of public art across Naarm city spaces, time and relationships.

Angelina Hurley reminds us of the significance of colour in our lives in honouring her father Ron Hurley’s work, and his significant contribution to Black painting, art education and exhibition histories, while artist Dameeli Coates writes of locationality in understanding sovereignty, in weaving and movement, and the inevitability of change across generations.

Filmmaker and community storyteller Tracey Rigney tenderly holds place on Country where she continues to live and work in a range of creative and environmental fields. In contrast, Timmah Ball’s woven meditation on Blak sovereignty threads urban places and resistance together and comforts us at Warrior Woman Lane in inner-city Naarm, named in honour of Lisa Bellear and her life’s work in photography, community life, broadcasting and poetry.

Two women drawing powerful inspiration from Indigenous online spaces are spoken word poet and activist Lorna Munro and photographer Hayley Millar Baker. Lorna celebrates the power of Blak women in lipstick and the Land Rights movement. For Hayley, the spirits speaking to her during her quick emergence as a successful young Blak artist have acted as protector against the toll that white hunger for her ‘story’ has had on her body and mind.

Artist and scholar Katerina Teaiwa describes creative resistance and the importance of storytelling as a justice of remembering. She calls for a future ethical praxis that stands against the desecration, unsustainable agriculture and mining in solidarity with Pacifica and Island Nations whose lands are most vulnerable to rising sea levels brought about by climate change.

Poet, podcaster and health worker Dominic Guerrera honours and celebrates the love, knowledge and strength and of his Elders in the twenty years since the Von Doussa judgement that overturned the Royal Commission on the Kumarangk/Hindmarsh Island Bridge ruling Ngarrindjeri women were not ‘fabricators’ of their cultural knowledge.

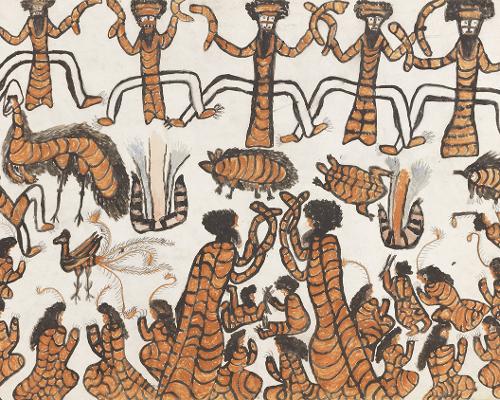

Our reviews were undertaken despite balancing the state-wide COVID-19 lockdowns and gallery closures, which had a huge impact on many of our writers cut off from community, family and Country. In Bryan Andy’s review of WILAM BIIK at TarraWarra Museum of Art, we see in William Barak’s example Wurundjeri visual sovereignty from the 1890s held for future generations. Navigating the challenge of distance, young and emerging writer Lady Shania Richards gives a personal reflection on WATER RITES at ACE Open in Tarntanya/Adelaide. In closing, Terri Janke acknowledges the loss of, and the legendary work of visualising sovereignty as lived and practiced by the late B. Marika.

It is intergenerational Indigenous collective strength and clarity of expression that is required as the Country calls to us: these expressions are creative, visionary and not reductive or exclusionary. It is the critical kindness of our Elders that we reflect on, and their patience and ability to be strong and work collectively.

Footnotes

- ^ This river that like many of the previously living waterways of this country is now devoid of much life. When I was a child we could catch yabbies in the creek near where we lived on the Kaurna plains, now there are no fish or yabbies, as the run off from the drains and roads poisons these riverways.

- ^ Melissa Lucashenko, “Writing as a Sovereign Act”, Meanjin Summer 2018 https://meanjin.com.au/essays/writing-as-a-sovereign-act/ accessed 30 November 2021

- ^ Lucashenko

- ^ See Audra Simpson, Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across the Borders of Colonial Settler States, (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014)

- ^ Jodi Byrd, The Transit of Empire: Indigenous Critiques of Colonialism, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), xvi–xvii

- ^ Karen Martin and Booran Mirraboopa, “Ways of knowing, being and doing: a theoretical framework and methods for Indigenous and Indigenist re-search”, Journal of Australian Studies, 15:76, (2003): 203–214

- ^ Rickard’s lecture was delivered on 11 September 2020 as part of the “Image Complex: Art, Visuality and Power in the United States”, organised by the Power Institute and Discipline Journal

- ^ Alexis Wright, “What happens when you tell somebody else’s story?”, Meanjin, 75:4, (2017): 58–76.