1968 is over (it’s over) 1981 is over… future is now.

In zeitgeist fashion, German punk/opera diva Nina Hagen adapted her lyrics when performing her bilingual hit Future is Now to reflect the moment, but the best-known recording on NUN/SEX/MONK/ROCK is contemporaneous with Artlink’s birth in 1981. As incoming editor in Artlink’s 40th year, I have both the benefit and the burden of the archive. I won’t repeat here the twists and turns, the highs and lows, that Artlink matriarch and founding editor Stephanie Britton summarised at each significant milestone as the decades rolled by, but I will say that each year the magazine’s endurance was further tested, while its achievements and people were celebrated. In 2014 Eve Sullivan’s first issue as editor Sustainable? Artworld and real‑world ecologies further implicated arts publishing and the vulnerability of all our creative ecosystems. But despite the perennial challenges, there is a glue binding the community of writers, artists, editors, designers, board members, curators, educators, advisors and readers that long-time allrounder Stephanie Radok captured in her editorial in the 20th Anniversary Reflection: ‘Artlink has always upheld ideals of accessibility, social justice and treading lightly on the earth.’

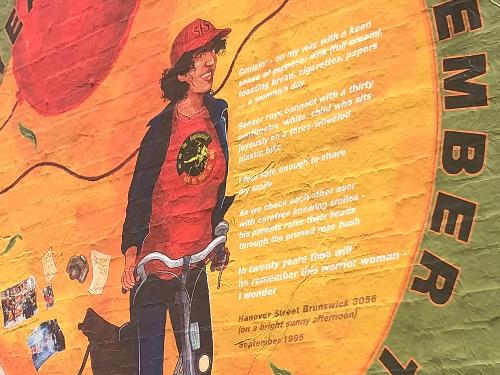

Twenty years on this moral coda has been amplified in everything that Artlink does and represents. Whatever our imprint disclaimer says, we are collectively of the same feather, and we remain deeply beholden to our values: unlike (the unlikely attribution to) Groucho Marx, (‘if you don’t like my principles, I have others’), we don’t actually have others. Artlink is in the paradoxical position of having built the status of an institution, but one that often rails, with varying angles and impact, against ‘the establishment.’ Many of Artlink’s long-standing contributors and ardent advocates came of age in the decades of progressive social change. (There is not the space to mention names here, but a cursory dip into the archive will expose them all!). Others began their intellectual and creative work in the transgressive decades of the 1980s and nineties, but whether—and how—Artlink remains a destination for articulate thinkers of all stripes and the critical debates they stoke is the burning question, and work, ahead. And I don’t mean hazard reduction. A fearlessness has underpinned Artlink through its changing inheritances and shifting publics, and while we don’t have money to burn, we do have an exhilarating program mapped out for 2022 including new online commissions, mentoring opportunities for writers and editors and wrapping up the digitising mission: we won’t be resting on our eucalyptus.

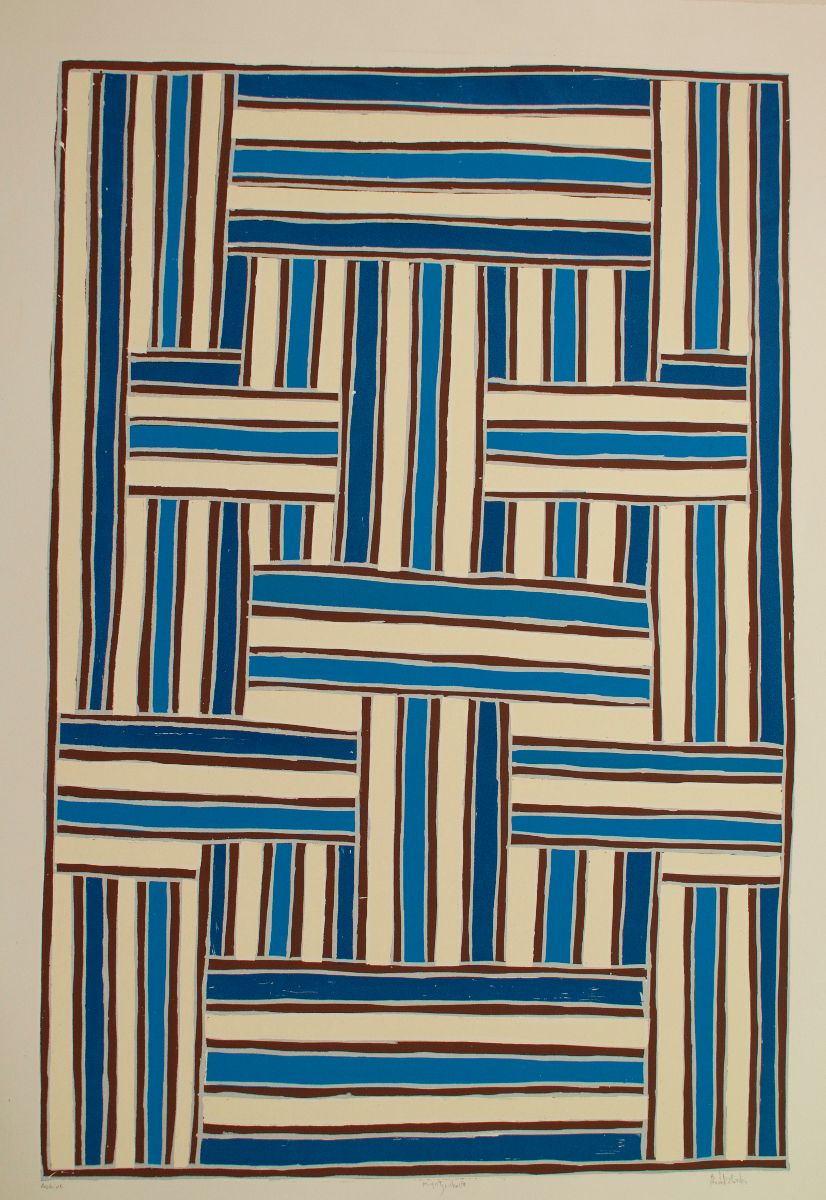

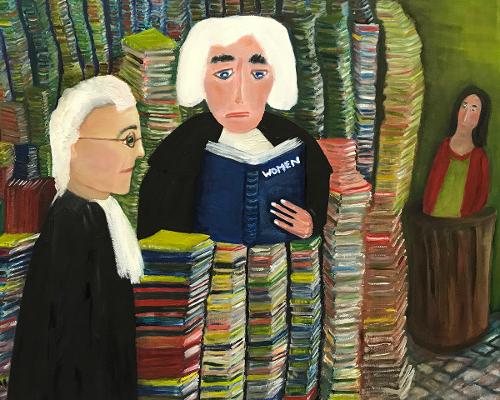

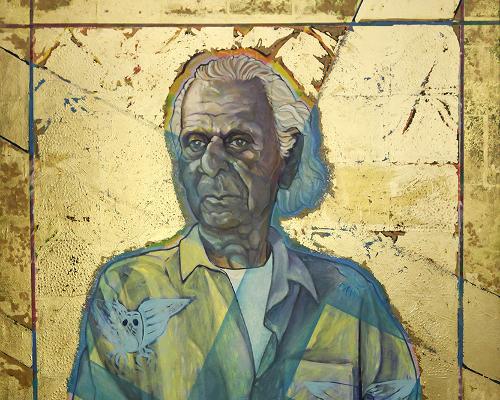

For longitudinal readers of the magazine, ‘…accessibility, social justice and treading lightly on the earth’ translates directly to Artlink’s commitment to First Nations art, culture, people and voice. Artlink has been a mirror to wide-ranging topical issues and national debates, and like so many institutions, the magazine only began to seriously reflect and proportionately shift its centre to Indigenous content following the 1988 Bicentennial of British invasion/colonisation. Landmark issues of Artlink, Contemporary Australian Aboriginal Art (1990, reprinted in 1992) and Reconciliation? Indigenous art for the 21st century (2000) offer great historical value as collections of diverse writers all deeply engaged in and with their subjects.

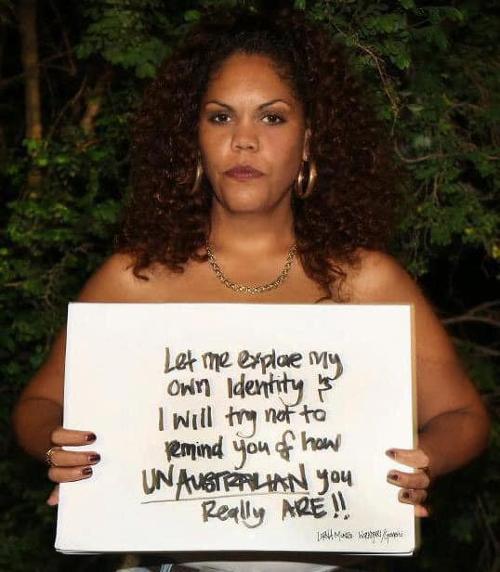

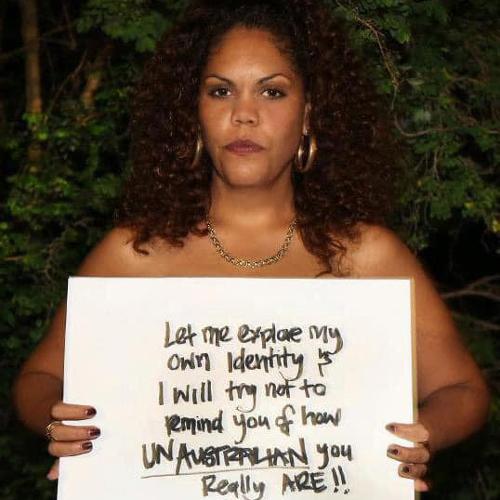

In 2010 the inaugural Artlink Indigenous: Blak on Blak, edited by Daniel Browning and Tess Allas, launched what was to become an established and celebrated feature of the Australian publishing calendar, and a resource that supports so much of the ongoing work of education, documentation, collaboration and that complex ideal, reconciliation, which requires consistent goodwill from all quarters. At a formal level, Artlink have just had our Innovate RAP (Reconciliation Action Plan) endorsed, but the real work is evidenced in the growing archive: every Artlink Indigenous issue, led by an impressive list of Indigenous guest editors, has courageously taken up topical concerns, redefining codes of creative and cultural practices, criticism, research, language and politics. Today we can be collectively optimistic about the increasing platforms for First Nations writers, artists curators and editors to speak, to be heard and to shape the conversation. To that end, each issue is an essential document of its moment in time and place, and Visualising Sovereignty under the direction of Ali Gumillya Baker and Paola Balla captures the zeitgeist of today in no uncertain terms: 2021 is over…future is now.