I enjoyed the first International Limestone Coast Video Art Festival and was always ready to come back for more. But the focus of this year’s program on “Video art during and after the pandemic” took its delivery to a whole new level of comprehensibility in response to Covid-19. Our increased reliance on screen time driven by peak media saturation, restricted movement, social isolation and quarantine has proved to be a galvanising impetus (also going by the number of entries to the open call-out at around 1,800).

We all know what video and its live functionality through services like Facetime or Zoom can do on call turning us all into broadcasters, streamers and filmmakers. As C.J. Taylor, one of the panel of selectors, enthused, “video art is a slippery beast, and we all have the means to make it in our pockets, on our phones.” For festival curator and Riddoch Arts and Culture Centre director Melentie Pandilovski, a long-term devotee of video as an artform, this networked space is witness to the anxiety of living in uncertain times, a space of invention and dire prediction that is also filled with humour and the need for “entertainment in the face of catastrophe, deep contemplation, solidarity, community, mindfulness, risk-taking, compassion and cheerfulness amid self-revelation.”

A starting point in many works is how to survive a life in lockdown. Three Months Quarantine by Irene Segalés, filmed from March to June in Barcelona, combines footage of deserted town squares, apartment-to-apartment views, glimpses of the lives of others at different times of the day and night, washing drying, raindrops swelling, plants in pots. Accompanied by an affecting soundtrack, it builds up to the now-familiar prolonged moment when the community comes together on their balconies to clap and celebrate workers, relieved that it’s over (for now).

Other examples take a more precipitous edge. Endless is a short film by Saroosh Ali in which a young woman at home alone ignores the advice of her social media app to time out, only to suffer the consequences of information overload in the time of Covid-19. Tales of the Balcony by Kinetta as a “Decalogue of survival,” presents the rules of engagement (“Rule no 1: Avoid anyone. Others are the enemy”) and advice for self-maintenance (“Maintain use of your legs”, “Do what you do best”, “Hug yourself as you do others”) only to chart a progressive loss of control as the contours become increasingly blurred. Stay at Home by Arnaud Laffond, a remarkable work of animation as a graphic daybook, unfolds like desert island imaginings in cyberspace, in which the fragile state of the subject is defined by the collision with built surfaces. “Day 3: Quarantine makes us stay at home, but how does it look afterwards under this roof?”.

Video art comes in many forms, and this core capacity to mark time and find poetry in motion, just by turning on the record button to capture an embodied experience is a fundamental creative act as gestural as painting. Here the confines of a room, a house, a rooftop or a restricted view replace the edges of the canvas. With something of the quality of early experimental film, bodies in motion, often spectral, monochromatic as silhouettes in the reduced light, fill the space of the surreal house in Akbar Aliasghari’s CPR and Zlatko Cosic’s Descend. Adding bodily weight, Felipe Bittencourt test out relations between beings and things in Support demonstrating two routines with a chair, while the protagonist in Panida Petchara’s Beetle takes to the floor like the human turned insect of Franz Kafka’s “Metamorphosis.”

Frustration is rampant in works that include Daphna Mero testing the rule of the perimeter limits by dancing the rooftop in Can you count to 100 and Maïza Dubhé’s dramatic lunging contortions in front of a camera placed on the floor in 8 x 8. Taken in as a group there is solidarity here, and this is given further emphasis in Linde by three young Mexican women, Citlali Rojas Pedroza, Jazmín Rojas Perez and Lizbeth Xospa Cabello, who with a fourth performer undertake simultaneously screened actions working the space of their confinement in the home, united in their desire for freedom of movement and expression through the shared condition of a woman’s body.

What to do in a space of confinement includes the studio or workplace as a closed set in practices that might now appear normalised as displacement activity. As an example of this, in a work that might be a remake of a performance by Mike Parr, Cynthia Schwertsik’s Double Check #31 shows the artist obsessively repeating an action portrait by crushing art paper over her face and scrubbing the surface raw with charcoal before discarding it. More self-effacing than revealing, Schwertsik herself appears to disappear as she retreats to the back of the studio. And, in a further display of messy “German” materiality, Isolation Number One by actor/director Idan Weiss follows two young performers playing the space of a large workshop filled with the leftovers of discarded production around which in their youthful passion fuelled by narcissistic urges they perform a duet like a dance of death with Covidian overtones (the body soiled and wrapped in plastic).

An enigmatic and elegant work that perhaps best enables this sense of being surplus to requirements is Aeonium by George Drivas. Part of the curator’s selection, this film premiered earlier this year at the Annex M/Megaron, Athens Concert Hall, in an exhibition called Structures of Feeling. At the Riddoch it is displayed as the central piece of the exhibition across multiple screens in the stage space. Here the actions are as mystifying as the snatches of conversation overheard. “I often wonder how we got here.” “Perhaps we are doomed now.” In the film we see a succession of workers in a vast greenhouse filled with succulents, attending to the “black flowers” of the film’s title. Yet, in a strange twist of the Gaia principle, far from being cultivated or nurtured, these plant specimens are shown being progressively cut down and dismembered as an indicator perhaps of an ever-unravelling state of collective mind.

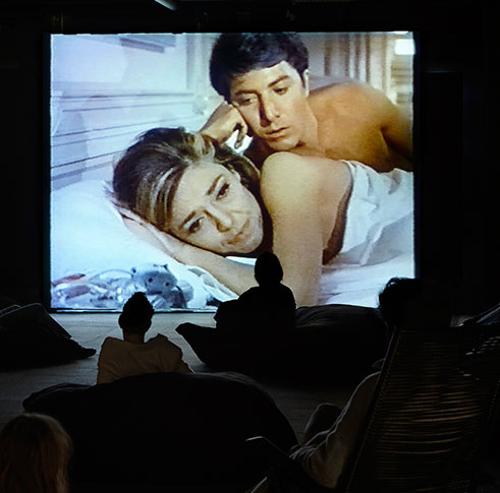

.jpg)

More focused on communicating the facts through bold storytelling, a work by Fiona Davies from her series Blood on Silk, Shutting Down in Isolation, extends the reference to the progress of the pandemic, drawing on Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal. Davies’ narrative voiceover in this work accompanies the view of a large gloved hand placing, turning and replacing wrapped toy figures on trestle blocks as hospital beds drawing on the artist’s recent research into death and dying in an ICU. Less a fairytale than a blow-by-blow account of what to expect based on what is currently being played out in hospitals around the world as the infection rates once again surge, this dramatically simple but impactful work lends its weight to the “techno-scientific upsurge” overlapping the socio-political crises that Pandilovski argues is the media message for now.

.jpg)

Video as the artform most likely to capture the very “story of our survival,” as Pandilovski claims is given a run across many works of diverse expression and style too numerous to mention here. The virus is a metaphor of its own vast dimensions that doubles the work of the electronic image and its neuronal stimulation of the eye and the mind. Like a virus, this fluid chemistry of the image is progressed in the creation of virtual worlds including Sentinels of Saturn by Luke Pellen, Tunable Mimoid (Giesian Paradox) by Vladimir Todorovic, Transient by Alessandro Amaducci, Metatrophic by Ash Coates and Alluvium by Erin Coates. In this space of regeneration and replication, the ecological, microbial universe gains traction as respect for nonhuman agency.

In further works that respond to all-too-human feelings, a scene in Stay at Home by Arnaud Laffond graphically animates the spread of the virus as an unstoppable fear, one of several excellent works of animation that include Stepless by Nadège Jankowicz and Works of Boredom by Natascha Jokic, Simon Schäffeler and Manuel Hoppe. Highly personal and poetic works that celebrate the hand-drawn image include those by artists Nenad Nedeljkov, Cristian Păsat and Anastasia Eremina. Mount Gambier itself is fast becoming a centre of excellence for digital art, as evident in the remarkable work by students and Mostyn Jacob whose Floating Through the Metaverse deserves special mention for its humour as a gamer’s parallel universe set in a retro-fit space age.

The program for the International Limestone Coast Video Art Festival is indeed futuristic, while already incorporating a sense of nostalgia in works such as Sink or Swim by Canadian artist Bruce Robertson Lansing, with shades of Australia’s own Peter Callas, prominent in the 1990s. Like the virus, this global media culture of the electronic or technical image, as Vilém Flusser conceived it, has only increased in its intensity, frequency and ubiquity as a presence in our lives. A transmissable world of pure surface that operates, as do our information networks, in a space of depthless simultaneity, is captured in works like John Baseley’s Virus: Obey the New Normal and Andrew Binkley’s Uncertain Times. These works that activate meme cultures, to also expand as visual essays of complex mediation like Tania Fraga’s Singularity: Interlacements of Virtual and Nature and Kristina Pulejkova’s Touch Screen yet continue to evolve around just such points of access, inclusion and reciprocity.

.jpg)