Greg Lehman reflects on his participation in The Partnershipping Project on its conclusion at the Burnie Regional Art Gallery in an interview with Pat Hoffie.

Nulla Sine Memore Voluptas (No Pleasure without Regret)

Pat Hoffie Looking back to when you were first invited to participate, what was it that drew you to The Partnershipping Project?

Greg Lehman As a historian and writer who has lived in Tasmania all of my life, I’ve been involved in a range of positions and roles that related to Aboriginal Community Development, Arts and Heritage. It remains a consuming fascination, driven in part by my ongoing personal exploration into aspects of my own relationship with Aboriginal art and culture. Central to the way I proceed is by progressively learning the language of history through not only information of the past, but also through a careful decoding of what we are presented with by the archive. I try to look at this process deeply and slowly. It is a cumulative or an iterative process, and this is what led me steadily into art history. This research has unfolded as a trail of mystery and intrigue into the visual aspects of Aboriginal culture and its relationship to world culture.

Two years ago, when I was invited to be part of The Partnershipping Project, my initial response was one of reluctance. I already had enough on my plate to keep me busy and engaged. And yet, during the conversation with the curator a key point in the discussion — the invitation to actually make as well as write – retuned me to a line of research I had been engaged in for some time. The invitation seemed to fit.

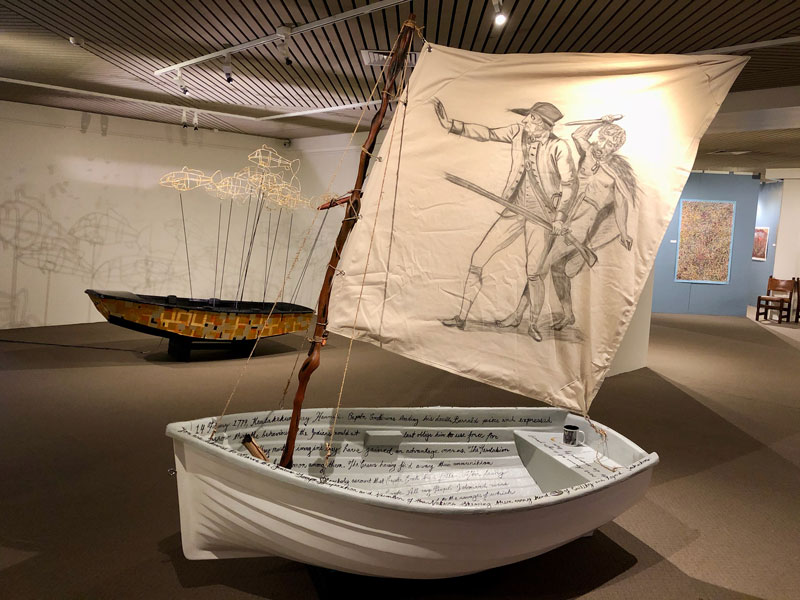

This research was focused on a sketch by John Webber, the artist who travelled with Cook to Van Dieman’s Land in 1777. The drawing depicts Cook offering a medal to a group of Aboriginal people. I realised through our conversation that one of the many things suggested by that simple image was the start of the involvement of the First Nations people of Tasmania in global trade and commodification. And while the event was performed as a kind of abstract, faux act of diplomacy, represented the beginnings of British colonialism in the land of my Aboriginal ancestors, it also powerfully echoed some of my ideas about global trade.

These are the points at which the objectives of The Partnershipping Project presented interesting synergies for me.

Pat Hoffie The fleet has now returned to Burnie Regional Gallery. How do you feel about it two years on?

Greg Lehman It’s clear that the final form of the exhibition, as well as the project’s original intention, was upheld. What I respect most about the project is that it’s succeeded in holding to its original mission, which at a surface level appeared to be relatively simple, but was in reality a complex challenge: the idea of using eight small boats as a vehicle and a location for the making of art, while not really knowing what was going to unfold at each of the four exhibition locations. The unpredictable elements of the journey were part of the project’s appeal and somehow capture the inherent chaos of globalised trade that is commonly perceived as economically rational – in the same way that art creates material presence from the mercurial impulses of artists to make sense of our mad world!

Also challenging was the fact that the work of a number of artists comes to an end at each of the destinations. Even though there is a digital record, most of the boats travel forward with ghost versions of their compatriots from the previous exhibition. When the hull of my own boat was selected by Gail Mabo in Townsville, she used it in a way that incorporated a whitewashed version of the text I’d applied to the inside of the hull. In this way each of the previous works forms a palimpsest of what comes next. And in that sense the process of what happens throughout the project emulates what happens in the business of global trade. Commodities are remade and transformed.

An obvious example is when a Tasmanian forest is clearfelled; we understand that our trees are being woodchipped and exported. What escapes us is that this later comes back to us as a cardboard box around a flat screen TV. It’s no longer recognisable as the original product. It’s been translated and re-translated by a succession of processes. Its value has been changed. Its very meaning has been re-engineered.

First Nations people in Australia are caught up in global trade in a way that is illustrated by The Partnershipping Project – perhaps in a way that has not been done before. Our creative practice is little different to the work that any other artist does – it’s about pursuing an idea, a story, a view of the world – finding ways to express this as a tangible work of art. But when you drop it into that global swirl of trade, it gets re-presented, re-translated, re-contextualised, and re-made, and we’re lucky if the original motivations and intentions of the artwork survive those processes! It’s no wonder that many artists refuse to be identified as Indigenous. To do so puts us at the mercy of a market and a culture of reception and exhibition within which we are, also as people, bracketed off; exoticised or categorised as something Other. One of the project’s great strengths is that it inhibits that kind of categorisation.

Pat Hoffie You have often said that you see collaboration between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal artists as being extremely important. How well did this work in Partnershipping?

Greg Lehman The process of collaboration, an inherent part of the project, might not offer a way of avoiding othering but it does provide a means of working through it. It's a practical way of embracing the synergies and contrasts that occur across work by artists from different cultural and geopolitical settings. In the creative setting of Partnershipping this helps to disrupt postcolonial processes that function to separate Indigenous people from everyone else – processes that were put in place to legitimise the exploitation and commodification of Indigenous culture. Partnershipping reframes these processes to expose how globalisation exploits us all, while creating space for new conversations and collaborations to occur. For me, collaboration offers a means of following new pathways. These might explore ideas about a particular image of object, or about how these objects – in particular, art objects – move through history, accumulating resonances and layered stories as they trace and re-trace journeys across time.

Pat Hoffie The past year or two have been immensely disruptive, with natural disasters and, most recently, the pandemic. How do you think these events impact on projects such as Partnershipping?

Greg Lehman During times of calamity or catastrophe, art slips back into its natural place – into a closer relationship with the personal and the local – as a functional and central part of the life of people and their communities. All those infrastructures that drag art into the milieu of trade – and that have been brought to a grinding halt as a result of the current Covid-19 crisis – bring about a realisation of the extent to which the art market has been globalised. In times like these, the circulation of art returns to local gallerists, arts organisations and communities who step forward to pick up the game. Our art, our practice, and our perspectives can be refreshed by this return. We can shake off the dust of our global journeys in a place we can feel at home.

Pat Hoffie I wrote about the Hanseatic League in the original catalogue for The Partnershipping Project. You seem to share an interest in this through your art-historical research.

Greg Lehman The project’s initial premise in the catalogue traced the origins of globalisation to the undertakings of the Hanseatic League that formed in the twelfth century as a collectivised means of furthering trade. During earlier research into the ideologies emerging from Renaissance art traditions at Oxford I too had become fascinated by these early merchant cartels and their relationships with artists. As a result of one of these relationships, Dutch artist Hans Holbein (1497–1543) painted a portrait of Georg Giesz, one of the members of the League. The portrait was intended as a means of reflecting the merchant’s success (and his attractiveness as a suitor).

One of the ways you can look at that painting is as an example of how an artist and his art became complicit in global trade and commodification. The painting promoted personality and celebrity at a time when this was the exclusive domain of the wealthy and powerful. The subject is painted surrounded by the accoutrements of mercantile trade, indexing the moral and ethical framework of the time. Hanging on the wall behind Giesz, for example, is a set of keys, placed there to assure the viewer that he is a competent and secure merchant. But it is the security that is important, not the goods that he trades. They become immaterial.

In the same way, the nature of the commodities that are stripped from the places we call home do not matter. It is their value in these systems of trade that is important. No one in these globalised systems cares about the tree, or the place from which it came, or the people who honoured and loved that tree. Traded commodities are there to simply energise these global systems of power and security. World trade today is equally amoral. It disregards place. It is ruled by commerce, not community.

As an artist, Holbein is not blind to this dimension. He incorporates contradictions into any simple reading of the work, and inscribes the merchant’s personal motto – Nulla Sine Memore Voluptas [No Pleasure Without Regret] – next to a set of scales behind Giesz. The picture plane is sprinkled with memento mori – a glass vase suggesting fragility and wilting carnations the impermanence of life and love. Holbein includes the reference to each of these human emotions as a means of holding a pictorial tension between the subject and life; between commerce and humanity.

Pat Hoffie Do you think this has also been the experience of the artists in Partnershipping?

Greg Lehman For many of the participating artists, The Partnershippping Project reflects the pain of present-day realities, through the everyday impacts of globalisation. So many of the works reflect sadness and deep tragedy. Greg Leong’s work for the initial exhibition in Burnie, for example, reflected an eloquent appeal to reconsider the contribution of Chinese immigrants to Australia’s history and culture. This work, by an artist of such huge standing, was one of beauty and sadness. And the fact that it had to be left behind, as the fleet moved forward, moved the work’s role into that of an ersatz contemporary version of this project’s internal memento mori. Another work that was “left behind” was Joan Kelly’s installation of tiny, beautifully intimate records of her quiet meditations on the northern Tasmanian shoreline. There’s such a rich sense of place in these images – conceived slowly and quietly over time.

These beautiful, fragile, transient works that summon the collective memories of this project aren’t lost; rather, they reinstate art an essential aspect of memories of place that matters immensely. And I think of your own experience as the curator of this project over this time, and of this broader process of crossing into the boundaries of the unknown. These are the real things about being alive – about being human – and they all become entangled in the central core of the project as art pulls us that little bit closer, just as Holbein was bringing us closer to the realities of his own time.

As The Partnershipping Project has unfolded, it’s revealed rooms within rooms as part of the overall framework. We can look back on those images, stories, reflections, documentation and analysis now to consider what’s transpired. There aren’t too many projects that reach quite so far into these deeper processes of being.

.jpg)