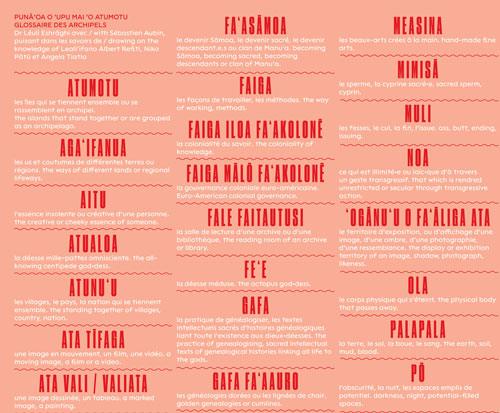

Everything, together: Partisan ecologies and painting

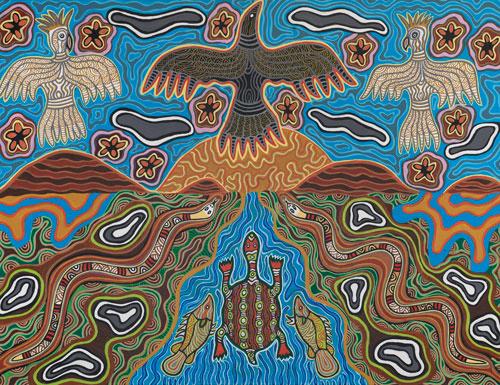

When you travel to Yirrkala one of the first things you notice is the lack of division between the waters of the Arafura Sea and the vast blue sky. Indeed, the smooth, honey-coloured shore seems to blend in effortlessly with the liquid of the ocean as the water laps its edges. If you take the time to sit in the shallow water just near the beach, away from lurking crocodiles, it is warm and silky. Once immersed, you begin to understand how it is possible to feel a part of something much larger. Things slow down. Once I saw a mass of butterflies move as a soft group across the top of me as I sat in waist-deep water, and a stingray meandered past, not concerned with the human in the water. The clear air acts like a conduit. During times of tropical storms that lash the coast and send stabs of water shearing up the rocks on the edges and boundaries of this place it becomes electric, humming.