Bush Women: 25 Years On, the Fremantle Arts Centre’s exhibition and publication project, might be interpreted within a broader trend in exhibition-making towards commemoration. A host of recent exhibition projects nationally have sought to reflect on significant historical events prompted by the passage of neatly rounded intervals of time: 400 years since the death of Shakespeare or the landing of the Dutch on the west coast of this continent, 200 years since the publication of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s Frankenstein; 100 years since the ANZAC landing at Gallipoli, followed, three years later, by the Armistice; 100 years of the readymade (or 50 years since Duchamp’s death); 50 years since The Field 1968 at the National Gallery of Victoria; 40 years since the Women’s Art Show in Adelaide. The last two speak to a not-unrelated curatorial trend of re-staging exhibitions, either in spirit or in quite literal terms, and an associated re-calibration of art-historical interpretation to accommodate the context and relations produced by exhibitions. Many of these projects have sought to critique the events they reflect on, but the format of the anniversary exhibition tends for better or worse to reinforce the gravitas of the event commemorated within a European or Anglo‑centric historical canon.

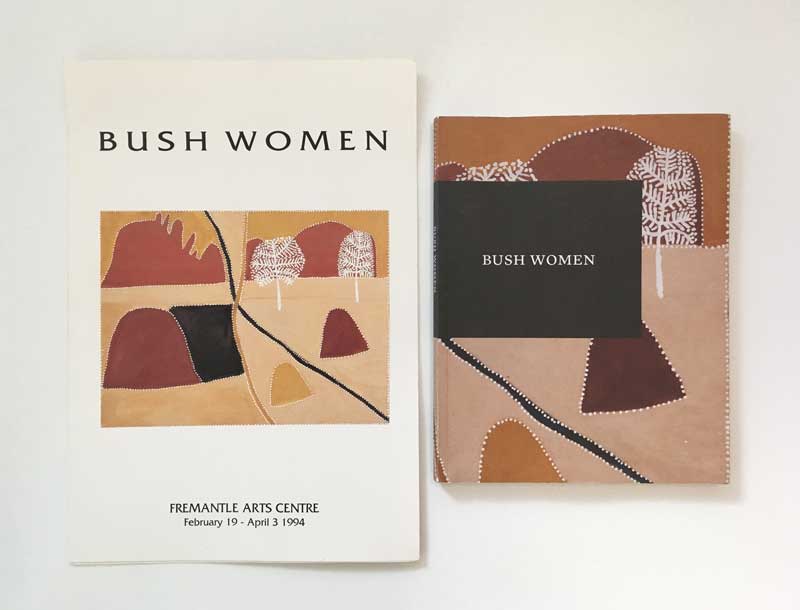

Bush Women: 25 Years On is a remarkable project because it works with these tropes to very different ends. The exhibition marks the anniversary of an exhibition held at the Fremantle Arts Centre (FAC) in 1994. Curated by then-FAC exhibition co-ordinator John Kean, Bush Women (1994) brought together for the first time the work of six artists – Daisy Andrews, Paji Honeychild Yankkarr, Queenie McKenzie (GaraGara), Tjingapa Davies, Tjapartji Kanytjuri Bates and Panjiti Mary McLean – working in communities spanning the Western Desert and Kimberley regions (Fitzroy Crossing, Turkey Creek, Warburton and Kalgoorlie) bringing the artists together in Fremantle as artists-in-residence. The impetus to re-visit 1994’s Bush Women came from an ongoing FAC endeavour to process and make accessible exhibition archives made prior to the advent of digital record-keeping. Invited to poke amongst the archives, academic and writer Darren Jorgensen identified the significance of the exhibition via the original Bush Women catalogue: a basic A4-sized 8-page brochure featuring a list of works, artist biographies, a hand-drawn map and Kean’s curatorial essay.

Kean has returned in 2018 as a consulting curator and contributing essayist. The restaged exhibition largely replicated his original layout and design, including painted wall treatments and zig-zagging partitions. About half of the artworks shown in 1994, tracked via the archives by now-FAC exhibition coordinator Erin Coates with assistance from Sheridan Coleman, also reappeared. These were augmented by working drawings, artworks produced in-situ at FAC or in a period roughly commensurate to 1994. Expanded labels for each work traced not only content or specific relationships to Country but also the trajectory of each object in the intervening years through time and space. These embedded details, offering more nuance than the average didactic panel, acknowledged the complexity of forces that produce value, culture and significance, documenting significant personal relationships – often long-term productive friendships between advocates and artists – changing ownerships including donations to public institutions, and the wax and wane of the Aboriginal art market over the intervening quarter-century.

Whether through limitations of timeline or a desire to situate it as parallel to but independent from the exhibition, much of this meticulous and illuminating detail – information Coates and Coleman describe in their introduction as having been fastidiously located and hard-won – has not been included in the 2018 publication. Complete lists of works for both exhibitions remain tethered without ISBN to the “unwieldy” institutional archive, as noted in the introduction by Erin Coates and Sheridan Coleman. What the publication offers instead is an expanded social history of the 1994 project,a non‑linear tracing of the relationships that produced and were produced by it. Longer-form essays by Kean and Jorgensen accompany reflective texts on situated art practice from Mary McLean, Daisy Andrews and Paji Honeychild Yankkarr reproduced from a 1994 edition of the now-defunct Fremantle Art Review, and from the catalogue of a 2005 exhibition by McLean held at Tandanya in Adelaide. Documentary photographs of the 1994 exhibition, artist talks, residency, desert and bush landscapes, as well as full-colour reproductions of artworks from the exhibition/s and beyond them illustrate each text.

Bush Women differs from other anniversary projects most obviously in that it privileges the diverse voices of Aboriginal Australia, mediated through an encounter with the white artworld but still central in the making and re-telling of their own histories, but also because the moment it examines occupies a more recent past less settled as mythology in collective Australian memory. For these reasons, it offers a useful tool with which to reflect on and trouble the ways in which that memory is made. From a 25-year vantage point, the recent past of 1994 is framed by Bush Women as a period of possibility, experimentation and opportunity for both the productive renegotiation of relationships between Aboriginal and colonial Australia and for contemporary arts organisations able and willing to facilitate such encounters though art.

Both Kean and Jorgensen note the creation and consolidation of a substrate of contemporary art galleries and institutions in the late 1980s and 1990s with a desire to look beyond the white metropolitan norm. Each chart exhibitions and events of personal influence in the lead up to and aftermath of 1994. Kean notes his recruitment from Papunya Tula to the founding team of Tandanya in Adelaide in 1989 and the Perth Institute of Contemporary Art’s 1993 project Yarnangu Ngarnya: Our Land – Our Body, for which twenty Ngaanyatjarra artists-in-residence transformed the building through installation and ceremony, with certain areas restricted by gender. Jorgensen reinforces Kean’s role in shaping many influential exhibitions, leaping forward in time to more recent projects including the Fremantle Arts Centre’s 2012–13 exhibition produced with the Martu people of the Western Desert, We Don’t Need a Map, also helmed by Erin Coates. The publication is peppered with admissions of limitation by its white authors (Kean, on Tim Leura Tjapaltjarri: “… my myopic fascination with ethnography stymied a more nuanced understanding of time …”) and with statements of loss and trauma (Andrews: “The Country is empty now. It made me cry”), but is also characterised by a profound optimism towards the potential of art and the artworld to continue in its negotiating role.

The period back to 1990 has already been memorably historicised by Ian McLean in his introduction to How Aborigines Invented the Idea of Contemporary Art, as a time in which the substantially white Australian artworld came to accept and theorise Aboriginal artists as self-determining agents of a global contemporaneity. The infinitely looping spectrum of global and local influence that characterises contemporary art theory is particularly influential on Jorgensen’s long-form essay, which speeds through a network of relations produced by what he terms the “Western Desert Diaspora” – the movement of communities from their ancestral lands into closer and more volatile proximity. Elsewhere in the book, Daisy Andrews also articulates the relationship between displacement and the high-key perspectival renderings of water, rock and sky in her paintings, with eloquent directness: “I went to visit this country for my mother and father. I was feeling very sad, it made me sorry. When I first went to Kaningarra I didn’t know that place … I first went when I was an old woman … People were killed there, policemen killed the people. That’s why my parents left ... .”

In examining a broad range of Western Desert art, Jorgensen introduces comparisons with both European diasporas and European abstraction. But he also goes to great pain to produce a history in which the encounter with Western Desert art also privileges other encounters that, while remaining irrevocably connected to colonial violence and interruption, operate beyond these logics. Thus, while R. B. Kitaj’s First Diasporic Manifesto and Rosalind Krauss’s expanded field might assist in understanding a relationship between the dot and groundlessness in Western Desert painting, the use of “saltwater colours” in Yulparitja painting must also be acknowledged as a direct homage to a new Country adopted after the waters of the Great Sandy Desert began to dry up as a result of mining, sorcery or the “Country left in want of its songs of rain and rejuvenation” when the people left.

Jorgensen’s ambitious text has some unevenness, particularly in relation to the significance of gender. While it is appropriate that Bush Women isn’t casually grouped with the many exhibitions of (predominantly) all-white women, a reluctance in the publication to substantially address gender results in some confusion regarding the analytic framework. For example, Jorgensen makes it clear that diasporic influence is “not defined by ethnicity or religion, but by social conditions or processes,” with occasional stabs made at a gendered analysis of form that recalls assumptions about Western abstraction easily countered by simply referring to different artists, or even artworks. While the restricted particularity of women’s business in remote communities is acknowledged, with reference to Queenie MacKenzie’s revival of women’s ceremonies, universal feminine qualities of softness, quietude and a quotidian domesticity are uncritically evoked elsewhere: “by the 2000s even Papunya Tula’s high formalism had been feminised, its women turning the powerful, rectilinear compositions of the 1980s into a hazy op-art …” Referring to Una Rey’s essay “Women in the cross cultural studio …” Jorgensen notes her anti-essentialist claims for intersectional feminism, but immediately follows with a description of a third wave of Aboriginal women making art that is “not only feminine, but also feminist, as they push against the masculine refinement of the dot and the circle”.

Rey’s text appears intended to complicate any obvious conceptions of gendered subjects or styles applicable across cultural boundaries, instead examining – among other things – the role that white female artsworkers have played as facilitators compared with their more directly authorial male counterparts. She notes via Vivian Johnson that Geoffrey Bardon’s “foundation story about Papunya Tula has been ‘retold so often and so widely that it has the force of a Dreaming Story itself’” and also that “the generative creative force of capital F feminism has plateaued, and may have limited traction against the trauma of colonisation …”[1] As the product of both sustained academic research and direct personal experience, Bush Women both theorises and produces a proximity that belies the vast physical distances between each of the six women at its core. A description of Fitzroy Crossing as being just “up the road” from Balgo, for example, paints a thirteen-hour drive as a trip to the corner store.

Through the subjective relationships of its authors to the places and artworks they describe each text produces an elasticity of distance and difference brought into sharp relief when Kean describes the artists meeting at the art centre in 1994, presumably for the first time: “who in the company of peers from distant communities, understood that they were part of a larger group of ‘bush women’ whose voices were beginning to be heard.” While this might be somewhat disorientating, navigating without a map or a timeline – being differently orientated through familiarity or loss – is a valuable experience for someone (like myself) whose worldview is so implicitly shaped by the orienteering of colonial Europe, and also by a west-coast artworld that repeats to itself a metro-centric narrative of separateness and isolation. To this tacit erasure of cultural production, and of interrelationship, influence and agency, Bush Women also offers an important counterpoint, tending towards the truly national perspective often lamented as lacking in the west.

Kean addresses the subject of orientation directly in his sensitive essay that describes the development of a curatorial method aimed at replicating the spatial experience of desert life, where geographic relationships are infused with another totemic geography of memory, story and ceremony replayed over time. In making exhibitions with remote communities Kean would “first, identify and locate key thematic episodes or ‘locales’ in geographic relationship to each other, to create a model of the relevant world/subject within the gallery spaces … Secondly, determine ‘way finding’. This process involves clarifying narrative paths between these major locales.” Kean applied this method in determining the layout for the 1994 Bush Women, aiming to replicate in the Fremantle Arts Centre spaces both the geographic and narrative connections between each artist. This would, he hoped, produce an experience commensurate to those described by the artworks themselves.

In reproducing this layout again 25 years later, while allowing for each artist’s work to be supplemented by both new works and new dimensions for interpretation, Bush Women: 25 Years On therefore moved beyond the commemorative reinforcement of other exhibition recreations or anniversary projects. Collapsing time and space permits, to quote Kean, “a circular understanding of time, in which the power of place is renewed and transferred to a new generation through the process of ceremony, storytelling and painting”. This among many of its exemplary qualities is what makes Bush Women: 25 Years On, both the publication and the exhibition, unique among the history-making projects that it might be compared to. This re-creation, in Kean’s words, both narrates and transcends time, suggestive of an “everywhen” that respects and enacts the simultaneity expressed by the artists’ works. In this space, the past is not just a place we temporarily and safely revisit, but a lived space for which we are responsible: now and forever.

Footnotes

- ^ Una Rey, “Women in the cross-cultural studio: Invisible tracks in the Indigenous artist’s archive” in Jacqueline Milner and Catriona Moore (eds), Feminist Perspectives on Art: Contemporary Outtakes, London: Routledge, 2018. pp. 38–50.