My old Aunties used to say, “the silences are more important than the words.” It is a reminder that what might be seen as empty in one culture may have deep meanings in another. It provokes reflection on the way in which we deal with absence and silence – and that even the concept of “empty” is filled with meaning and context. These are the range of ideas that are explored in Void, a new exhibition of Indigenous artists. Emily McDaniel is a curator who seems to hunt quietly and thoughtfully.

She notes, “the void is a politicised space that cannot be defined as simply an absence or a presence.” Her placements weave a series of thematic juxtapositions and synergies that fill the space. She pulls together seemingly eclectic pieces as though she's patiently sewing a possum coat. Once complete, the separate pieces fit seamlessly together in a thought-provoking and beautifully crafted whole that offers a myriad of reflections about the dominant culture’s idea of emptiness.

The literal centrepiece of the exhibition is Jonathan Jones’ haunting and evocative installation, dhawin-dyuray, axe-having, 2015. As one sits between the walls of a constructed space, one sees the moving outline of hillscape in shadow, as though it is one’s eye that moves along the outline of country when it is really the country that is leading you. But the real sense of being within country comes not from imagery but from the richness of a soundscape that weaves wind, rain, bird life and the sound of an axe.

The axe sound is produced from an axe that uses a stone from Jones’ own Wiradjuri country, creating a sound that pre-dates colonisation. Jones has become one of the most prolific and important Indigenous artists of our time. His work is steeped in cultural regeneration of practice and language. It is collaborative and community and Elder led. In this piece, he shows the pulse of unstoppable time, the hints of destruction against timeless elements. Our connection to country is visceral and within empty space one finds they can feel active space, living space.

Juxtaposed with Jones’ constructed landscape sits a series of works by James Tylor. Tylor is an artist with a rich cultural heritage – Nunga (Kaurna), Māori (Te Arawa) and European (English, Scottish, Irish, Dutch and Norwegian) Australian. He draws on that and uses photographic methods and a central part of his creative practice. In his (Deleted scenes) From an Untouched Landscape #12, #13, #7, 2013, and (Erased Scenes) From an Untouched Landscape #14, #2, #8, 2014, Tylor takes classically composed rustic landscapes but carves out geometrical space from them.

From a distance, they appear as sculptural elements placed on landscape but this is an optical illusion, causing one’s view of the works to shift and refocus, to question one’s perspective and understanding. These forceful images speak to the destruction of country that is an inevitable consequence of colonisation, of the carving up of Aboriginal land. They also speak to the loss of people and the loss of culture from the land as a part of the colonisation process. In this way the spaces or voids literally cut from the landscape are rich with the reference of the deep cultural and spiritual connections that Aboriginal people have with their land.

Speaking back to Tylor’s work is Hayley Millar Baker's installation Meeyn Meerreeng, Country by Night. These dark black volcanic and granitic rocks have a dark reflective surface. Placed in formation, they evoke the image of a riverbed, with stones weathered by water. Sourced from Millar Baker’s birthplace in Wathaurong Country to symbolise and reflect on her ancestral lands in Gunditjmara Country, the rocks were cleansed before being painted black. This is with the intention to seal the stories within them and protect them. It evokes the notion that there are ways in which non-Indigenous people may see a landscape but a deep knowledge of the place, contained in ancient stories, remains unseen by them. What may look like nothingness actually contains deep knowledge.

One of the provocations of this work is that it highlights a fundamental difference between Western concepts of knowledge and Indigenous concepts. In the former, there is a view that all knowledge is available for us to obtain; in Indigenous cultures, there are strong protocols about who can know what. While some knowledge can be shared, some can only be shared with people who are initiated or of that place – and with knowledge comes relationship and responsibility.

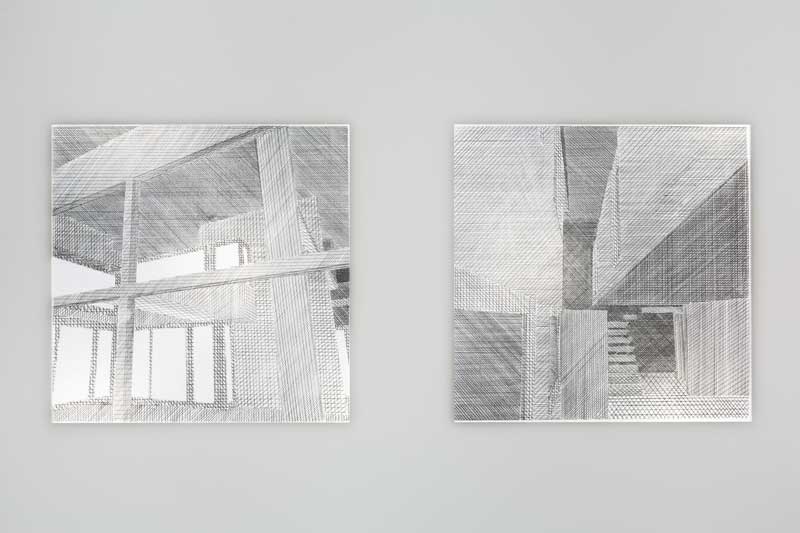

In Untitled, Eisenmann by Hand, Speculative Design, 2013, Danièle Hromek has imagined a modern space. A Budawang and Yuin artist and designer, Hromek has been inspired by the experimental work of architect Peter Eisenmann. Representing her own perspective and cultural worldview, she rethinks the concept of space by creating an architectural possibility worked through delicate lines. In this way she elicits reflection on the spaces we create in our mind, the spaces of imagination.

In a profound way, Hromek’s structural imaginings, through the delicate lines, seem to weave back to the mesmerising motifs of John Marwurndjul’s ochre on bark, Mardayin Design at Milmilngkan, 2003. This is a representation of a ceremonial site, a space of cultural significance and knowledge. The painting contains sacred and secret meanings that can only be known to the knowledge holders. It is another point in the exhibition where Western concepts of knowledge are challenged and where the viewer may see one layer of meaning but not the many other layers that lie underneath.

Similarly, Peetharee Story: Dugong and Emu, 1980, by Dr G. Thancoupie holds ancient cultural knowledge that can continue to be passed down. One just needs to know how to see it. She decorates a delicate hand-built earthenware vessel with a story of country. Of the earth, this crafted artefact is imbued with knowledge through the design that links to ancient story. The vase itself contains a space. While the vase might seem empty, this “story pot” is actually full of meaning and knowledge.

Transmission of culture, story and knowledge is also present in the work of Ngemba artist Andy Snelgar. This gifted carver, who follows traditions handed down from ancestors with both his Woomera, Miru, 2017, and Shovel, BaBarr, 2017. These utensils, sculptural carved and decorated wood, have multiple meanings and uses as they represent the transmission of knowledges of ceremony, story and lore handed down for generations after generations. The deep cultural meanings of the carvings mean that the parts removed by Snelgar leave behind important messages, the spaces have as much meaning as what remains.

Complementing and contrasting Snelgar’s artisan and artistic practice are the works of Jennifer Wurrkidj and Josephine Wurrkidj. The thin, delicate sculptural work of these Kuninjku artists depict mimih spirits, important cultural figures that are believed to predate the presence of humans and so have gifted knowledge, song, story, dance and other cultural to the first peoples. These spirits inhabit the world that cannot be reached by the living, they live in the void.

Senior Gija artist, Mabel Juli’s stunning work, Garnkiny Ngaranggarrni (2006), although abstract is in some ways the most literal in its concepts of void. With a black backdrop, stylised white representations appear that represent Ngaranggarrni stories that are told in the sky. The night sky is often presented as a vast empty space. By contrast, Indigenous narratives inhabit the space between the stars, making the dark spaces places of active storytelling. What might seem like vast blackness is not so much the absence of light but the absorption of all light, of all meaning.

In his essay that accompanies the exhibition, Professor Bruce Pascoe writes, “these images and objects are not to be glanced at … they are to be looked at, considered, absorbed. They are of country, our shared country.” Pascoe’s meditation reminds one of the constructed concept of “void” that was one of the great lies of colonisation – terra nullius. There is so much rich cultural detail and practice inhabiting the exhibition it mocks the absurdity of an assertion that Australia was a country without people or systems of government, that it was void.

The legal concept of terra nullius was not so much predicated on a conceit that the country was empty of people; it was more an assertion that the country was without a system of governance and laws. But accompanying this legal concept of terra nullius was a psychological terra nullius. Non-Indigenous people looking at country did not see the stories, the song, the culture, the tradition, the connection, the responsibility, the custodianship. In a way, this has been the more enduring form of wilful blindness. While the legal system has over-turned the notion of a vacant country in the 1992 Mabo case, the psychological notion remains.

It is a striking similarity amongst all the works in Void that even though the explorations of the concept are rich and diverse, there is a commonality of cultural practice and tradition, all connected to country, that seeks to show how much exists in the space that so many Australian’s assumed was vacant. Through sketching, weaving, carving, sculpting, painting, through new technologies and old, this collection of works highlights the diverse way that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders across the nation are talking back to their country to reawaken stories as continuing cultural and creative practices. It is a silent revolution that most Australians are not aware of. As Emily McDaniel says, “the void is a complex space of exclusion and inclusion, definition and deliberate ambiguity.” In understanding our country and our relationship with it, sometimes the silences are more important than the words.