.jpg)

Let’s begin by stating the obvious, Intramuros (within the walls) is not Manila, certainly not contemporary Manila which is pithy travelspeak for everything Philippine. This “city” walled up in 1571 by Spanish conquistadores imposing themselves upon this former fort of the chieftain Rajah Matanda was in fact the very first gated territory in the Philippines. It was initially meant to set apart Spaniards from natives, as well as Chinese traders and other non-colonists made to step away from the walls by nightfall. Only certain sections of its once contained 67 hectares basically made up the sites of the recently concluded first Manila Biennale as the artist-organisers rented state-run spaces under the remit of the Intramuros Administration.

So when Manila Biennale Executive Director/Producer Carlos Celdran frames his launching of the effort, doing so by harking back to his own dissatisfaction with growing up as an isolated and thus clueless denizen in a Makati enclave, the irony gets magnified. Even more so, when we come upon Manila Biennale’s tag of “bringing back the soul of the city,” that is, even when Intramuros makes up a mere 1% of the present city’s entire dominion. It is nostalgia for a privileged past that the Manila Biennale appears to anchor itself upon and it is something that artist–organisers perhaps need to reconsider more deeply when they summon the courage to do this all over again.

The fiddling with framing is critical precisely because all biennales come entangled in questions of representation and history, no matter how passionately the curatorial and publicity rhetoric denies these. Over four centuries past the time conquistadores walled themselves off from the local population, Manila remains most certainly a magnet of contested interests: gateway to those first encountering the country, landing hub of would-be internal migrants escaping rural poverty, and most recently gambling complex contender in the Asian region.

Elsewhere on Manila’s storied Roxas Boulevard (beyond the walls) lies a freshly installed memorial to Filipina comfort women forced to service the sexual needs of the Japanese military as they laid claim on the Philippines in 1941–45. The work, which was greenlit by the National Historical Commission of the Philippines, is being asked to be taken down by the Japanese diplomatic corps. That sculpture alone could make the case for saying that Manila’s soul does not exclusively emanate from Intramuros’ stone walls.

Even in the still largely Catholic Philippines, the hubris of associating an “authentic soul” with a once exclusive domicile of the colonial and then local elite ridiculously betrays class-blind thinking. Embarrassing references to pre-war Manila’s being once the Paris and New York of Asia diminishes the street cred gained from positioning this Biennale as community-oriented. Yet this was unfortunately the rhetoric which underpinned an otherwise brave attempt at staging an artist-run bid to make room in the overheating market-driven Philippine artworld.

The Manila Biennale came sub-titled as an Open City, the “open city” peg deliberately referencing the failed attempt to save Manila from the military bombardment and pillaging which marked the end of WWII (approximately 100,00 casualties in Manila alone). Sadly, the “open” in Open City also became fodder for the biennale’s critics decrying the cost of festival passes despite the freebie first weekend and how non-ticketed sites (where certain performances and street art were installed) remained gratis for visitors, and a pay-what-you-can scheme for single events like the Transitio concert and artist’s ball were part of the programming.

.jpg)

By sheer happenstance during the biennale’s run, one could have hailed a pedicab that was part of the artist-priest Jason Dy’s project which engaged willing pedicab drivers in his work, Procesion los Camareros. Retrofitted with an image of the old San Ignacio Church (now Mission House), the pedicabs as conveyors of images and faith, drew from the annual procession for the Immaculate Concepcion, a community event prevented from taking place by the Japanese occupation in December 1941. Each pedicab carried a self-fashioned reliquary that each of the drivers filled with objects they ascribe as sacred. Meanwhile, down Plaza Roma was the Latvian artist Aigars Bikse’s functional sculpture, Red Slide which neighborhood members helped install and which their children mounted with abandon, making the piece very much their own despite the estranging post-1989 European reference.

As a fledgling effort, the Manila Biennale expectedly ran into common biennale predicaments: aborted participation, stymied permits, wayward technology, petty thefts, and so on. But it did get off the ground and held its own for the whole month that it ran, jacking up Intramuros’s visitor statistics in the process. “This is a rehearsal for the next one” is how head curator Ringo Bunoan and Celdran put it. As it joins other artist-initiated perennials in the country like the 15th VIVA-ExCon (8–11 November 2018 in Roxas City, Capiz), it will be instructive to see how they negotiate with sustainability and community engagement more mindfully. Sans illusions of pre-war European affinities, this biennale if it is to insist on being different can do much to engage with a complex narrative that has become the fate of many cities the world over.

And biennales have no monopoly on this. It is a script that extends beyond any single war, as capital flees to other newly gentrified sites and the urban poor are left to fend for themselves, literally creeping through the cracks of heritage quarters, which in the case of Intramuros is now occupied by schools, museums, government offices, transient seafarer quarters, and a sprinkling of cafes and shops desperately elbowing room amidst thousands of informal settlers’ makeshift homes. Birth pains notwithstanding, the Manila Biennale certainly had poignant moments amidst the daunting challenges. Apart from Procesion, among the pieces which most directly engaged with the thorny aspects of memory- and place-making were works by Boni Juan, Elnora Ebillo, Hikaru Fujii, Angel Velasco Shaw, Carina Evangelista, Gail and Marija Vicente, Tanya Villanueva, Agnes Arellano, Renz Baluyot, Kiri Dalena, Kolown, Teodulo Protomartir, Luigi Singson and Gerardo Tan.

But to say that the architecture was resolutely working in their favour would be an overstatement in many respects. Artists who installed in the still pristine, because newly reconstructed Mission House had more control over staging art under near museum-like conditions. It was a different story altogether for Fort Santiago though. Save for the holdout Rizal Shrine lying within Fort Santiago, one wayward Rizal bust, and slowly disappearing Rizal brass footprints, the Fort which is still a standard Filipino schoolchildren field trip, is now mildly associated with torture and imprisonment of locals including national hero Jose Rizal.

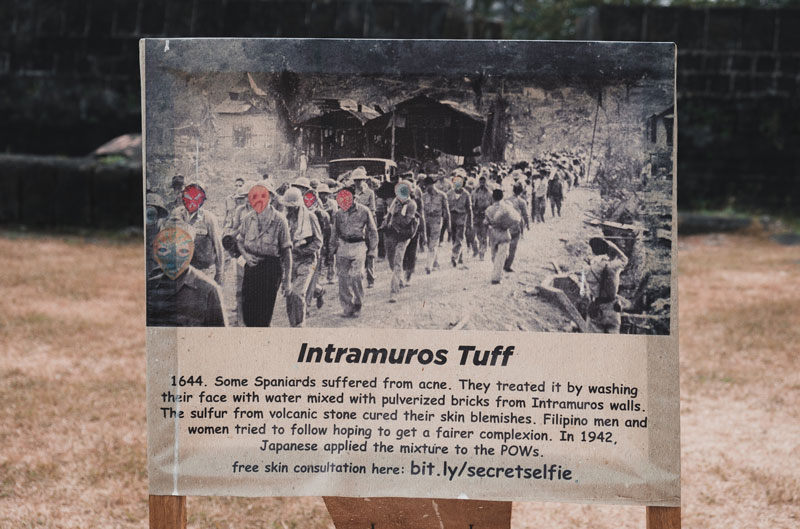

Fort Santiago is arguably a shadow of its former self, caught between serving up cloyingly prettified IG-friendlygardens and the need to keep some semblance of its lineage of violence and dispossession of human dignity. Presidential vintage cars, the former open-air theater of the Philippine Educational Theater Association, etc. once counted on the spatial historic pulse but eventually moved out, since replaced by generic snack kiosks and trinket shops. The state of such heritage sites turned event options is largely a story of emptied semiotic charge muted by often overbearing venue clients, save for the occasional Rizal martyrdom re-enactment done by Rizalistas and Battle of Manila revisits by the Philippine Living History Society. The one series of works that frontally took on this murky state of affairs was the Cebu-based collective, Kolown as they sacrilegiously mashed up historical fact with fiction in faux factoid signage strewn across the biennale sites.

While there were works that were evidently and deeply thought through in regard to siting and foot traffic, there were also very real life spatial incidentals that worked against the attempt to engage with the environment. Take Carina Evangelista’s Mando Plaridel which not only asked visitors to veer off the regular visitor tracks around the fort but to hopefully pick up on coded literary reference to the nationalist novelist Amado Hernandez along with an olfactory aspect, a scent associated with funereal flowers.

This work was presented in a quiet enough spot to pick up on the sobriety of the piece but was unfortunately closed off at one point halfway into the Biennale. Another victim of ambient conditions was a work among the front-end tunnels. I refer to Angel Velasco Shaw’s Inherited Memories painfully crafted from war reminiscences of family survivors, which was teamed up with Arvin Noguera’s sound work. Again, sadly the duo was no match for the sound system and carnival vibe that spilled over from the plaza just beyond the tunnel’s precipice.

Such exhibition-making dilemmas surface the trade-offs between strewing works in the path of instant but accidental publics, vis-a-vis setting off art in more clinical and way-off sites like the Mission House where Elnora Ebillo’s WatAwat would readily be recognized by locals as naughty wordplay on the Filipino word for flag. The haunting video projection set against gossamer material alludes to the fragility of a nation, literally hanging by a thread, fraying as killings of thousands of urban poor implicated in drug crimes mount.

But the wat/what (incredulity) and awat (plea to halt) in WatAwat is meant to play off elsewhere, to an unfolding and still being pieced together national story made harrowing by the weaving in of an aural track, a casual conversation between children attending the wake of slain teenager, Kian delos Santos. This subtle jab at the Philippine populist president’s centerpiece peace and order campaign layers an otherwise merely aestheticized ode to how strong women (the only visible figures in the projection) propel a narrative of nation. The subterfuge in turn brings up other questions: on the patronising as well as empathetic potentialities of the literal, and the measured doses poetry posits.

Boni Juan’s Kaming mga Busabos: Ang Kundiman ni Mariano Dimalanta (We the Oppressed: The Ballad of Mariano Dimalanta), and Hikaru Fujii’s Record of the Bombing occupy the extremes of that continuum. Juan’s paean to a zarzuelista-guerilla grandfather incarcerated in Fort Santiago registers affectively even when the personal backstory is not on hand. Such pictorial stand-ins for unfortunate souls could easily pass of as beings of this century. Dimalanta’s stark stare literally brimming from a metaphoric vessel of lives left to the mercy of flooded dungeons contrasts with the yawning void tha Fujii’s vacant museum vitrines evoke. The versatility of art’s methods of visibility is sent up dramatically in either case—Juan’s enabling a forgotten ancestor to surface, and Fujii’s calling attention to the obstruction of viewing what would have been taken as fact. Interestingly even if inadvertently, Fujii’s “failed” showing of WWII Japan artifactuality sends us back to that maligned comfort woman on Manila’s vaunted sunset strip, and how the sheer act of remembering ruffles the authors of official memory.

In toto, recurring projects like this city-anchored biennale will interminably become embroiled in debates about how public spaces such as Intramuros (and beyond) are apportioned and to what ends. Two decades back, University of York archaeologist and cultural critic Kevin James Walsh wrote how: “the heritagization of space in deprived regions is not designed to provide locals with cultural services, but rather to wallpaper over the cracks of inner city decay in an attempt to attract revenue of one sort or another.”

This skepticism over the way the heritage industry has taken shape in the West and how, on the pretense of art, poverty merely gets moved around or boarded up might give the biennale’s impassioned team of volunteers pause if only because the biennale does align itself to some degree of enlivening community. Presumably even more directly involving the very people who have the most stake in keeping the city afloat would be more judicious for the Manila Biennale in coming to terms with the sort of economic entanglements it is willing to wager its creative labour on. Needless to say, it ought not be merely about bringing the coiffured Makati-Pasig set to slum it in Manila in the guise of art pilgrimage. Nor do its future biennales need be just underhanded stabs at international biennale comeuppance.

With much of the art being undeniably powerful and sensate despite the multisensory elements and naysayers working against the enterprise, this writer admittedly felt doubly invested in reviewing the Manila Biennale. I was asked to do a workshop on art criticism in the early part of the public programming, so it did become a matter of walking the talk. Having contact with the biennale team gave me a strong sense that earnest goodwill was very much operative, with one volunteer tearing up visibly over an activity where children from troubled home environments had the opportunity to work with the Museo Pambata via the Bayanihan Spirit Hopping House project of Alwin Reamillo.

Independently walking about the heritage zone and striking up conversations with those who people Intramuros (transient and otherwise—seafarers, tourists, students, and informal settlers in it for the relatively long haul) show just how problematic it is to say that the city has “lost its soul.” In contextualising claims to vanishing heritage, artists posing themselves as contrapuntal to mainstream urban development rhetoric might more firmly distance themselves from pining for a genteel time of dons and muchachos.

Doing otherwise begs the question: why would those who have a life and death stake in Intramuros want to relive such inequity when it is already so vividly felt in the forlorn spaces of the present moment? One can only hope that when artists set out upon the walls again, perhaps they might also ask more pointedly, what could be made with and for the hardy and embodied souls who choose to abide by what President Duterte calls a dying city? Why would this city rally behind a biennale? Maybe then a keener looking beyond the ramparts could be attempted, since that is, after all where some 1.78 million souls do live, breathe, and still imagine a future albeit uncertain.