The driving forces behind this remarkable exhibition are the famously reclusive language groups making up the Anangu cultural enclave: the Martu, Pitjantjatjara, Yankunytjatjara and Ngaanyatjarra nations. Doomsayers once foresaw a ruinous future of “detribalisation” and cultural extinguishment for these last peoples to come into contact with the colonisers’ world. But the Anangu hung on against the odds and their society has regrouped and their culture prospered. A traumatic history of colonial contact (Woomera, Maralinga) made them wary of disclosing details of their Tjukurpa for far longer than others. More recently a willingness to explore the potential benefits of sharing the treasure of their culture with the outside world has emerged. It started with their celebrated contributions to the desert painting movement, from which they withheld their approval and participation for more than a generation. Now, in partnership with the National Museum of Australia – an institution struggling like the Anangu elders to maintain relevance into the 21st century – they have devised a spectacle which they hope will make their stories strong and whole not only for their coming generations but “for all Australians”.

This tour de force was seven years in the making from the day Anangu elder Mr David Miller asked a roomful of Canberra academics and museum personnel to help his people put their broken songlines back together again. The result is an exhibition that does justice to the holistic aspect of the Indigenous worldview variously known as Dreaming, Tjukurpa – and now Songlines – a term whose currency this show, building on the legacy of Bruce Chatwin’s 1980s bestseller, will guarantee into the future. Such is the breadth of the appeal of Songlines. For those new to the subject of Aboriginal spirituality the detailed mapping of every aspect of the story onto country achieved through an ordered sequence of paintings, photographs, objects and multimedia will be a revelation. For those familiar through the perfunctory annotations conventionally supplied with Aboriginal artworks supporting the idea that paintings encode stories, the complexity of the Seven Sisters’ characters, their psychological depths, the extensiveness of the narrative, the darkness and sheer raunchiness of the story that unfolds across these canvases will astonish and delight.

The land and its story really is the thing here, the artworks mere “portals to the land” to use the terminology of the NMA’s Senior Indigenous Curator Margo Neale. A woman of rare determination, she played a vital role in the years of negotiation to secure the permission of all participating communities and relevant cultural authorities necessary for the exhibition to proceed. Alongside Neale every step of the way was the seventeen-member Anangu curatorium for Songlines, made up of Martu, Pitjantjatjara, Yankunytjatjara and Ngaanyatjarra elders, a line-up of whom we meet in the Museum Foyer, life-sized in their light boxes, issuing a personal invitation to embark with them on the journey within: “Right, you with us?”, they say. Inside, across a field of stars, we enter the exhibition to find the first of several arrangements of life-size effigies woven from grass and coloured wool by the women of Tjanpi Desert Weavers. The Seven Sisters/Minyipuru/Kungkarangkalpa sit companionably together while their pursuer, variously known as Wati Nyiru and Yurla as their story unfolds across the territories of the different language groups, lurks nearby. It could almost be the beginning of the love story he fantasises with the eldest of the Sisters, but as he himself is finally forced to recognise, something about him is just “not right”.

Opposite this eerie opening diorama of desire and rejection is a painted map of Australia acknowledging that the Seven Sisters Tjukurpa traverses the entire continent, not just the sections spelt out in this exhibition. Indeed its reach is global: almost every culture on the planet to which the Pleiades constellation is visible has a Seven Sisters story. Most involve relentless pursuit by a lustful man represented by Orion. What makes this version peculiarly Australian – apart from the ribald and self-deprecating humour – is its absolute groundedness in the Australian landscape. As its title states, Songlines: Tracking the Seven Sisters sets out to track the Seven Sisters as they flee halfway across the continent, from waterhole to waterhole, hilltop to hilltop, pointing out as it goes the presence of ancestors in the landforms created by the women’s flight from their would-be suitor’s rampaging penis. The idea of mapping a Dreaming story onto the country over which the action takes place is hardly new in Indigenous art, indeed it is a core concept. But it has never before been done in such meticulous detail over such immense distances or with a story so archetypal and so compelling. Noel Pearson’s opening comparison with Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey seems quite apt – except of course that the Australian version is a work of collective genius. As is the exhibition: over one hundred artists from the Martu, Pitjantjatjara, Yankunytjatjara and Ngaanyatjarra lands and language groups contributed.

The art on display includes over sixty objects, twenty pieces of multimedia and six installations plus one hundred paintings, many of them large scale collaborations painted at the sites to which they refer. Among the highlights are the monumental Yarrkalpa Hunting Ground, hung adjacent to Lynette Wallworth’s three channel video installation Always Walking Country documenting its creation, and a dozen masterful pieces from the rarely shown Warburton Art Collection. Large format photographs and young Martu filmmaker Curtis Taylor’s dream-like offering intensify the experience of moving across the land in the Sisters’ footsteps. More of the Tjanpi Desert Weavers’ trussed grass sculptures of the protagonists illuminate key points of the narrative: where the women’s pursuer uses his magical powers to turn them into trees, where they take flight, taunting him with glimpses of their genitals and finally pissing on him from a great height. As their pursuer and ultimately the world are destined to discover, there is nothing helpless about the women of the Seven Sisters Dreaming.

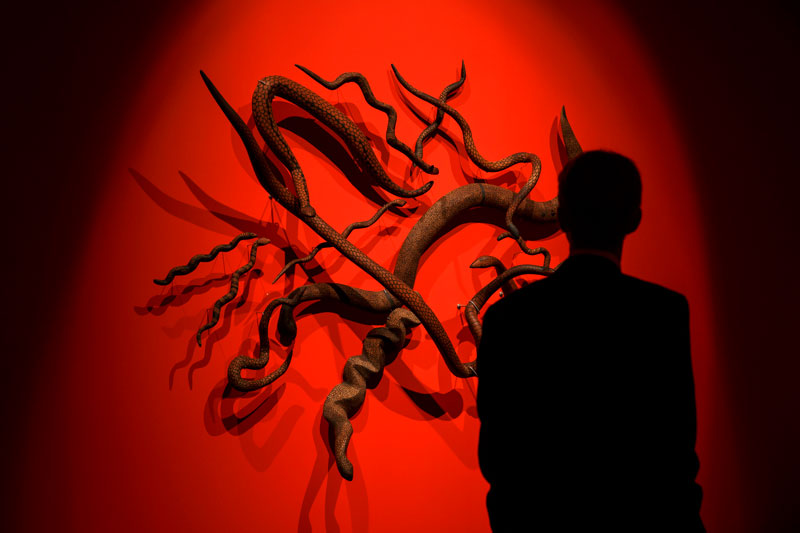

It is not all about the women. Anangu men share ownership of the Seven Sisters Dreaming, and see their role as protectors of the women’s right to the telling of it – even though their only appearance in the story is when a group of them are beaten senseless for having the nerve to ask the Sisters to marry and stay with them. “We never came for you. We are our own selves.” This is the women’s spirited answer as they take flight. Midway through the exhibition we come upon an all-red room, shocking in its intensity, lined with spears and a terrifying convolution of carved wooden snakes: suddenly we are inside the mind of the Sisters’ pursuer. Around another corner we are confronted with a huge photographic image of a glowering cliff-face at a place called Kuru Ala (“eyes wide open”). Two deep symmetrical caves form the eyes of Yurla boring down at the startled onlooker. At the very place where the sorcerer captures and does violence to the eldest sister, we experience a frisson of the fear that has gripped the women throughout the story.

Songlines: Tracking the Seven Sisters is no mere art exhibition dressed up as an educational experience to validate its siting in a social history museum. It is a journey from which most visitors will emerge overwhelmed, perhaps even with their understanding of Indigenous culture irrevocably altered. The centrepiece of the exhibition is the ultimate, immersive multimedia experience: the viewing dome for Travelling Kungkarangkalpa (2017). Beneath a cave-like hemispheric ceiling, the visitor lies prone as visions wash overhead The Walinynga (Cave Hill) Experience presents the never-before filmed ancient and modern rock art of Cave Hill with a clarity unattainable in the original. The Art Work Experience replicates the Sisters’ journey through the artworks comprising the exhibition, culminating in a vision of the Sisters as Tjanpi effigies taking flight for their eventual destination in the firmament.

Songlines itself ends not with the Sisters’ ascent into stardom but with a sudden fall back to earth as we take a poignant stroll through the last works of one of its most eminent artists. Tjapartji Kanytjuri Bates’ marvellously detailed and energetic mid 1990s canvases from the Warburton Arts Project light up the walls of the exhibition. Her final scratchy markings on pillowcases, bits of cardboard and every available surface are said to “grip the soul” in their determination to continue inscribing Tjukurpa to the last ounce of her strength. The last thing we see is the empty wheelchair to which the artist was confined at the end of her life’s journey – a reminder of the impending mortality underpinning the plea of the Anangu elders from which this project grew. This is their bid to engage the smartphone generation with their own heritage before they too move on to the realm of the Ancestors – or at least to see that these traditions are recorded in a manner that will ultimately engage the children of the cyber age. I also caught an echo of where the contemporary Indigenous art movement began. Of the impulse to make art with any and every means available as a pathway to Indigenous cultural survival, this multimedia extravaganza is thus far the ultimate 21st-century expression.