In Australia philanthropy and the arts have been infrequent bedfellows until recent decades. So in 1990 when seemingly modest New York couple Anne and Gordon Samstag bequested $5.5 million to the South Australian School of Art to establish an international travelling artist scholarship many initially believed it to be an elaborate prank. Earlier Australian patrons such as John and Sunday Reed rather personally championed modernist artists, art and literature during the 1930s to the 1950s establishing what was to become the Museum of Modern Art of Australia on the outskirts of Melbourne. Further north, J.W. Power’s substantial 1961 bequest “to bring the people of Australia in more direct touch with the latest art developments in other countries …” created The Power Institute and founded Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art in 1989.

Not unlike the far-thinking example of the independently wealthy artist and theorist J. W. Power, who abandoned his medical career, to study in Paris, and was well-known in the French art circles of the day, but not at all in Australia, the Samstags seemed uninterested in securing their own artistic legacy or reputation. Following on from the establishment of a teaching collection and exhibition venue (the link between the J.W. Power Bequest and the MCA), the Samstags’ vision was to mount a grand exhibition of international works and to enable recent graduates from Australia to travel abroad. And, while J.W. Power’s works were bequeathed to the University of Sydney by his widow remaining intact as a body of work as an odd sideline to the establishment of the Power Bequest collection itself, Gordon Samstag chose to give away or destroy most of his own art, with only a smattering of his wide-ranging oeuvre currently identifiable.

As personalities, the Samstags were far removed from the sensational tales of sexual intrigue and tragedy that emerged from the Heide circle gathered around the Reeds – a mythology which outlived them. The Samstags were decidedly old school. Both from influential and wealthy east coast families – Anne (Davis-Bigelow) tracing her ancestry to the 1630 Winthrop emigration. The Samstags were stylish and understated dog fanciers and sailing enthusiasts who played Bridge with a tipple of sherry.

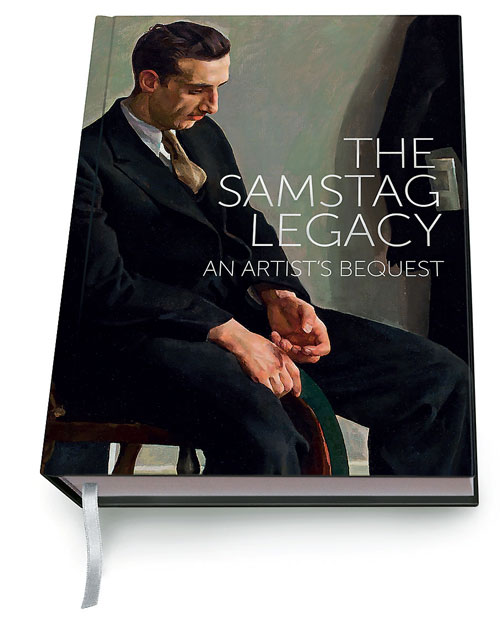

Uncovering the evolution of the bequest and the Samstags’ backgrounds is an intriguing tale – part archeological dig, part psychoanalyst’s couch. Edited by Ross Wolfe, The Samstag Legacy: An Artist’s Bequest is a weighty tome, lending itself to close episodic reading rather than a casual glance. Major essays, grounded in fifteen years of research by many individuals across two continents, provide complimentary, divergent and overlapping perspectives. Lea Rosson DeLong, a scholar of the American scene and New Deal art, examines Gordon’s art career in the USA until 1961; while Wolfe investigates the couple’s Australian years, the inheritance and their deaths in Florida, and the establishment of the bequest and scholarship.

Delving deeply into the culture and personalities of American realism between the wars, DeLong renders in considered detail Gordon’s activity and reputation. She excavates descriptions of many lost paintings; establishes his character and dedication to practice with insightful correspondences; proposes how he and Anne could have crossed paths; brings to light his career as an illustrator, and charts the upheaval wrought by postwar modernism. Wolfe situates the reader within the Samstags’ world via a familiarity developed from media culture: Gordon’s brother Nicholas, a writer at heart, lived in New York’s Dakota building and was promotions director for Time Magazine before starting his own advertising agency. Gordon would have visited Nicholas’ home (in the same building as John Lennon and Yoko Ono) and his office in the Time-Life building on Sixth Avenue, where the fictitious stars of Mad Men – Peggy Olsen, Don Draper and Roger Stirling – were also plying their trade.

.jpg)

I can’t help but think this book could have been a tête-bêche – a single volume in which two texts are bound together running head-to-tail. You read one side, then flip the book over to read the other. But almost imperceptively a third thematic is plaited through each discourse. This is the raison d'être for the establishment of the Scholarship – the history and politics of art scenes, education and institutions, and the opportunities afforded young artists in the USA between the wars, and in Australia from the 1960s onwards.

Almost nothing was known of Gordon Samstag, and DeLong’s remit was to uncover his early career. His family had not supported his choice to become a painter. He worked his way through art school and, while gaining critical and popular acclaim in the early years of his professional career, still struggled to sell his paintings. He emerged as a favoured student from the National Academy of Design, travelled to Paris for one year on a Pulitzer Travelling Scholarship and was awarded a Tiffany Foundation summer residency at their Long Island art colony. Set, one would think, for a sparkling career.

Then the stock market crashed. His stark style of social realism depicted ordinary working people—tired, despairing, beaten, without hope. The triangulated hand on an aching back seen in Proletarian (1934) and the pensive gaze of Nurses (1936) became characteristic of both contemporary and historical portraits of men and woman over several decades. Perhaps it was too real to be truly popular. Meticulously researched and rendered New Deal murals in Scarsdale, New York and Reidsville, North Carolina are perhaps his most enduring works of art, with several mural studies held in the Smithsonian.

DeLong charts trends in art, generating a palpable tension between realism and the provocation of European surrealism and modernism. Art education also swings to either foster or confine creativity, and classically trained and politically aware, Samstag fitted neatly into neither camp. The shallow plane of action in his paintings hint at his talent as an illustrator for popular fiction magazines, in advertising and of WWII training manuals. But for Gordon at that time, painting was the pinnacle of artistic expression. Anne, a textile designer when they married in Manhattan in 1933, was described with disdain as “doing something commercial” by one of Gordon’s colleagues.

With the violent postwar overthrow of realism, Samstag struggled to include more psychological content such as dreamscapes and the occult into his works. He promoted his paintings as having a “freer style and greater imagination” but exhibition opportunities declined. Although he established and co-directed the private American Art School in New York, Samstag’s shift towards abstract expressionism with puzzling compositions, obscure references and derivative work was never taken seriously. His work eventually ebbed from sight.

When, in 1960, the Samstags announced they were moving to Australia, friends believed they wanted to escape political unrest and the threat of nuclear war. Conversely, in Adelaide, rumors abounded that Gordon was a CIA agent sent to keep an eye on the UK’s Maralinga nuclear tests. Wolf concludes they sought a quiet retreat from the New York scene to secure a fresh start and simpler life. Like Australia's other major art benefactors, the Samstags knew the benefits of travel, of experiencing different cultures and art practices. As a young woman Anne had summered at Cape Cod then travelled by ocean liner on annual extended trips to Europe for her cultural education and Swiss schooling. Gordon’s year in Paris was personally significant, although DeLong did not detect an immediate stylistic influence on his painting.

Wolfe uses a broad brush to contextualise Australia’s art history and art institutions from British invasion; including Eugene von Guérard’s sublime landscape, Tom Robert’s bush realism, to the social observation of Grace Cossington-Smith and John Brack in the twentieth century. His portrayal of suburban Australia sears with a geographical isolation and philosophical narrowness only relieved by the diversity of art and culture brought by refugees from postwar Europe.

Anne and Gordon came to Adelaide at a time of change, with Gordon teaching at the South Australian School of Art from 1961 to 1970. The then new Adelaide Festival of Arts was effecting a more cosmopolitan city with international art and visitors. Gordon recalls these years, reconstructed through startlingly contradictory personal remembrances by colleagues, students and neighbours, as the happiest of his life. Elwyn Lynn and Bernard Smith mention Samstag favorably in print, and he was active in the Contemporary Art Society of South Australia, later becoming President with a plan to sell their building to raise funds for an international exhibition. Unsurprisingly, he stepped on many toes.

.jpg)

Despite his reputation as conservative and cantankerous in some local circles, his last years in Adelaide see Gordon experiment with many subjects, styles, mediums and materials. Perhaps he lost focus, or alternately he was reinventing himself for a new decade where art no longer demanded “careful preparation and painstaking craftmanship”. Wolfe speculates that his lack of major artistic recognition produced cynicism and bitterness. Yet I suspect that he was flowing with the Zeitgeist that consumed pop culture into the arena of fine art. Self-determined, in his later years he publically challenged the prevailing authority of art critics, curated his own shows, taught amateurs and participated with gusto in local art societies.

Secure enough not to be dependent on a consistent career, Samstag did indeed indulge in the playfulness and plurality of “anything goes”, the term used by Paul Taylor to headline the counter-cultural tendencies of “Art in Australia 1970–1980” in his influential compilation of essays published by Art & Text in 1984. The End of Galatia (1969) a painting from his scatological period, discussed by Wolfe with wry wit, was owned for many years by arts dealer and patron Kim Bonythan before being acquired by the Samstag Archive. Content aside, Galatia is not so different from the 1936 Nurses, with defined shapes, flat planes of colour and the stillness of white. As DeLong astutely observed of his work three decades earlier, Gordon is still “bound to the observable and drawn to the abstract.”

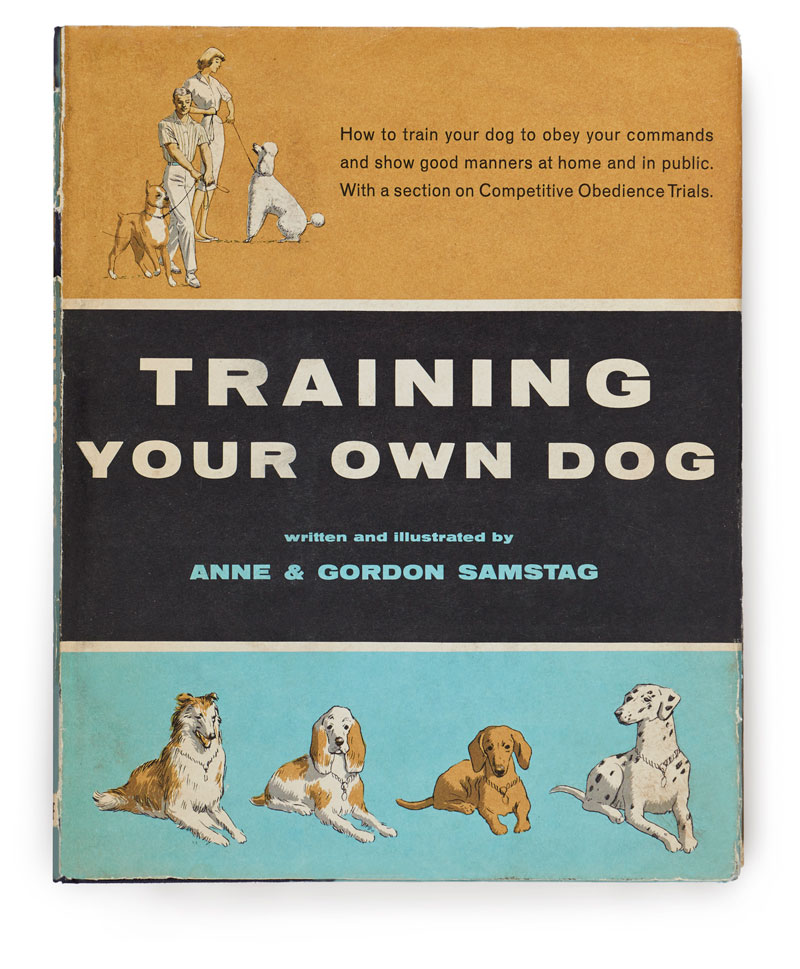

Anne’s story is more elusive. Quiet and impeccably dressed, she was a well-known dog trainer who wrote articles on the sport and conducted obedience classes in Adelaide. Gordon illustrated her book Training Your Own Dog (1961). She gardened and did charity work, but it appears her days as a designer had ended. Luckily, some of Anne’s beautiful and underrated tri-coloured, rolled-edge linen handkerchief designs from the 1950s have endured. Variously portraying her beloved poodles, leaves and domestic objects, these treasures can still occasionally be found on vintage eBay stores.

The establishment of the bequest and its beneficiaries is another major thematic of this publication. A Samstag Scholarship is a very large leg-up in the Australian art world and over the 25 years since its inception, 136 Australian emerging visual artists have been supported to develop their skills and abilities internationally, some becoming household names. Gordon’s original plans for a US component of the Bequest were hampered by his many controlling stipulations which resulted in the whole bequest coming to Australia. Local politics and a structural shift in educational institutions slowed the Australian process, however all was successfully resolved and the first ten annual Scholarships awarded in 1993.

Gordon’s will also secured his legacy in spirit, instructing that the scholarship selection committee always include the Senior Lecturer of Fine Arts at the South Australian School of Art, which had been his position when he was there. What constitutes Fine Arts now is another matter. Art theory and practice have evolved exponentially in the generation since his death. The fine now mingles with the amateur; social media performance and group craft projects are biennale-style events; artificially intelligent software undertakes digital and object design; remediated histories replace the original; and the once unthinkable has been resurrected as the ruminating Cloaca Professional by Wim Delvoye, a room-sized robotic digestive system, that produces a daily poo for gallery visitors at Hobart’s Musuem of Old and New Art (MONA). Gordon’s The End of Galatia predicted what was to come.

But getting back to the heart of this monograph, we have a tale of adventure, of success and disappointment; a tale of an odd but stylish couple – gracious hosts living a comfortable, contradictory, modern suburban life. In a moment of tenderness, Wolfe notes of Jewish Gordon and Quaker Anne “that they had found each other as partners in life is quite remarkable”. Gordon emerges for me as an eternal optimist. Yet, while many intriguing corners of his psyche are probed, I long to know more of the elusive Anne with her dogs and designs – the quiet heiress whose inheritance made this bequest possible.

DeLong’s fine-grained scholarship succeeds in mandating a revaluation of Gordon Samstag as a significant Depression-era painter. Rather than decline, his illustrations and postwar career need to be seen in the context of an evolving creative life; one that encompassed the passing on of knowledge and dedication to what Gordon most valued – independent thinking. Undoubtedly this publication will unearth new artefacts from the enigmatic Samstags, as painting, textile design, writing and sculpture are discovered in attics and dresser drawers, book cases and sheds. Meanwhile their generous legacy continues to invigorate the Australian scene by enabling emergent artists to explore the many manifestations of contemporary visual arts in the global context.

*Thank you Ross Wolfe and Eve Sullivan for conversations which contributed to this review.

.jpg)